Nudity and allegory in the spectacular paintings of Daniel Lezama

Lezama’s striking nudes embody Mexico’s rich culture

Daniel Lezama is a Mexican-American artist whose paintings are some of the most strikingly original art being produced in Mexico today. His richly symbolic works dive deep into the millennia of Mexican iconographic tradition to both re-interpret the past and create new expressions of contemporary life. One of the most noticeable characteristics of his work is the nudity of many of his figures – sometimes natural, other times body-painted.

The nude in Western Art has its own long tradition, and Lezama’s style definitely shows the influence of European masters such as Caravaggio and Goya. But the greater dialogue of his artistic output is with a decidedly Mestizo (mixed-race) and Indigenous Mexican populace of today. The nudes he represents phenotypically are, in their great majority, people you would see walking down the street in today’s Mexico City – not the idealized forms of Classical statues or Renaissance frescoes.

Lezama’s observations on painting nudes echo some of the basic beliefs of naturism regarding purity and truth: “Representing nudity means representing the truth or a form of it; removing the layers of meaning that society places on the body, the meaning it gives it through clothing, stereotypes, etc. Nudity always ends up returning you to primary meanings” (Yaconic).

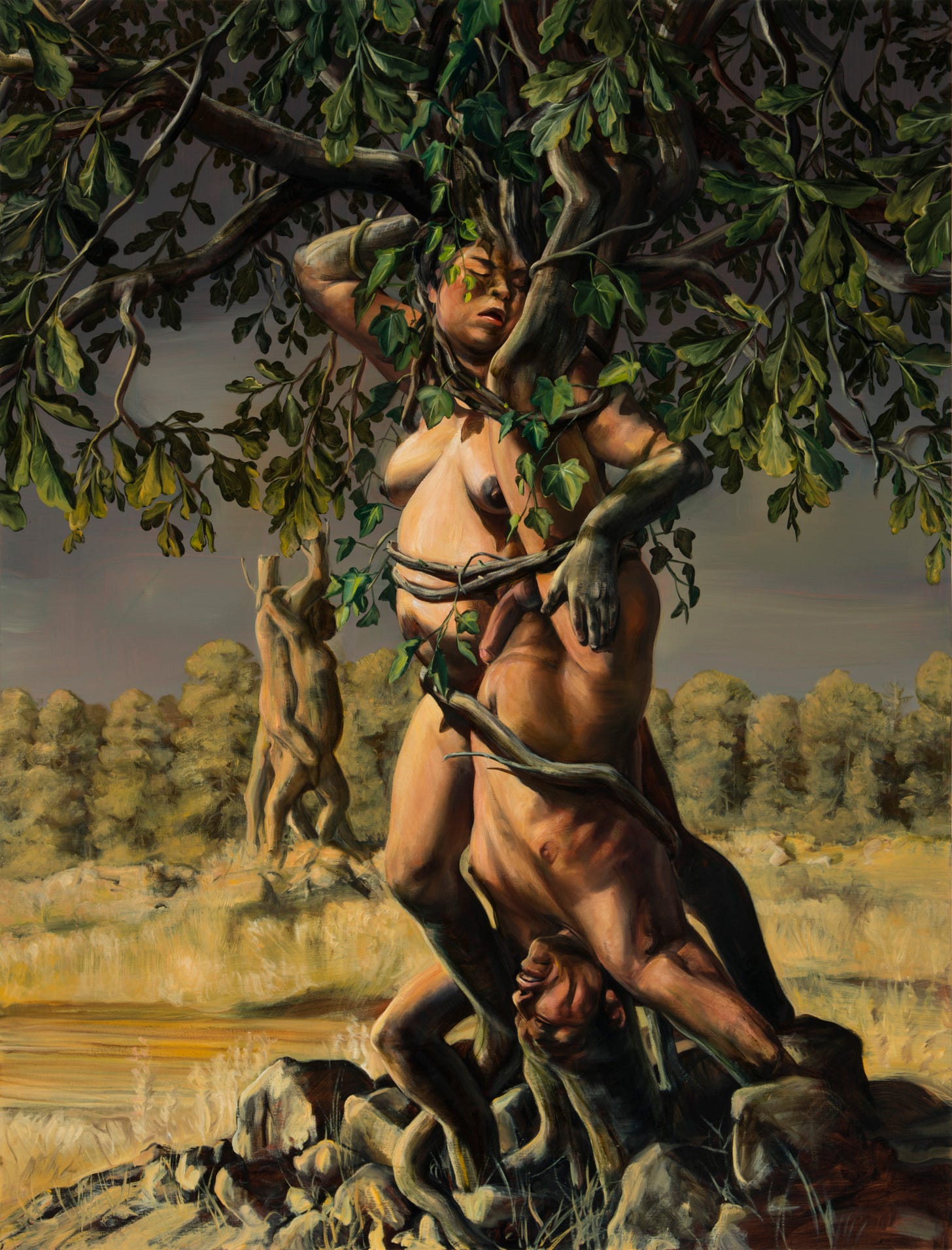

A good illustration of this assertion is his painting Otoño [Autumn]. This piece depicts an intertwined woman and man who form the trunk of a tree, its leaves beginning to wither. Her legs, and his arms (since the man is upside-down), form the base of the tree while suggesting its roots, and their opposite extremities form the branches while still appearing to be arms and legs. A dried trunk of a similar paired composition is visible in the background. The figures’ nudity and placement connect them to the natural world, in this case reinforcing the age-old and worldwide link between human and tree shapes, as well as a widespread association of feminine energy springing up from the earth and masculine energy emanating down from the sky.

Many of Lezama’s works, though, portray nude figures that are body-painted, often in one solid color. He often links the coloring overtly to Mexican patriotic symbolism, for example in Alegoría a la bandera [Allegory of the flag], where the green, white, and red-painted figures reproduce the color sequence of the Mexican flag. The central figure, who appears to be nourishing the green and red children, wears an eagle helmet and crushes a snake with her foot; she incorporates the flag’s central symbol of the eagle who has vanquished a snake with beak and talon.

Behind the trio is the majestic view of central Mexico’s famous volcano pair, Ixtaccíhuatl and Popocatepetl, linking the painting to many others in the history of Mexican landscapes. The figures’ nudity serves to represent them as clearly allegorical while simultaneously linking them to what real Mexican bodies look like.

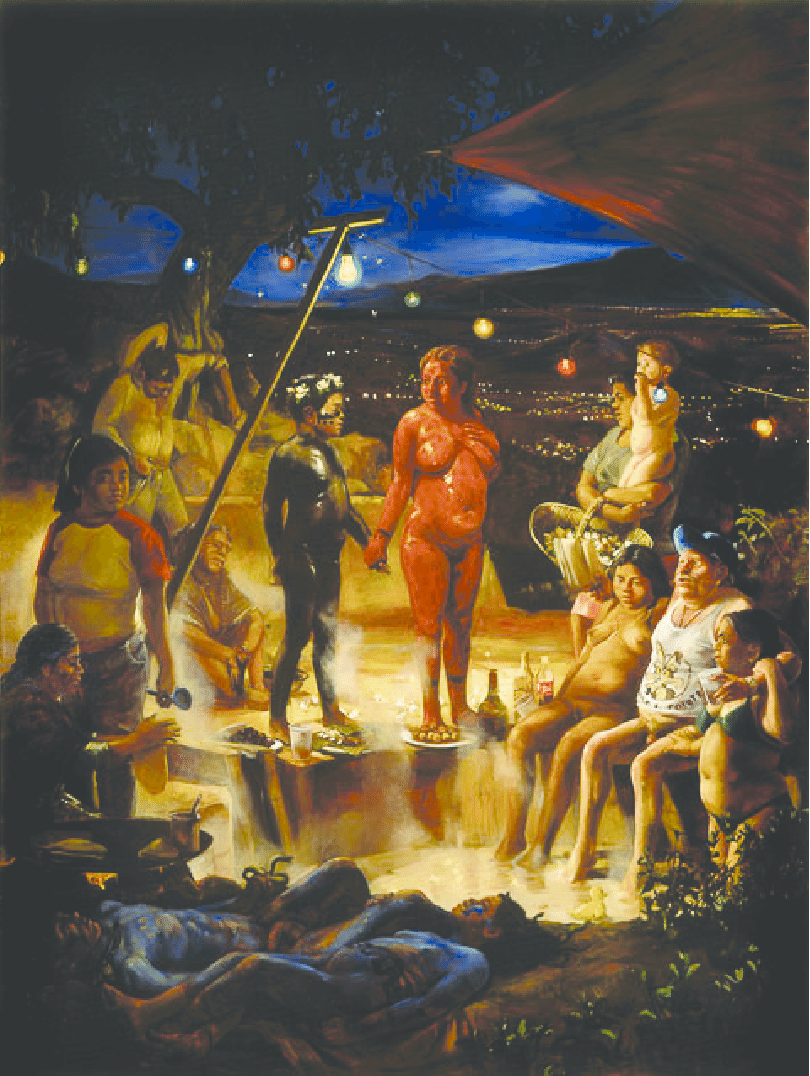

Lezama’s paintings are often sprawling works depicting many people at once, in a mix of attitudes, purposes, and states of dress. In Los baños de Netzahualcóyotl [The baths of Nezahualcoyotl], Lezama presents his take on a well-known archaeological site containing a spa park looking over the central Valley of Anahuac, designed by the fifteenth-century king Nezahualcoyotl. The painting showcases a mix of people—some nude, some dressed, some half-dressed—gathered around the iconic gourd-shaped bath from the king’s park. Perhaps oddly, it’s a scene that can be representative of many clothing-optional naturist settings. But four body-painted figures seem to send the work in a different direction: a male and female couple painted blue lie face-up in the foreground, and a high-contrast couple stands proudly in the middle of the canvas – a woman painted red and a boy painted black wearing a wreath of white flowers. Interpretation of the scene is ambiguous. Some see the blue figures as sacrificial victims, or as representatives of a dream world.

I see the red and black couple as an embodiment of the classical Nahuatl-language phrase in tlilli in tlapalli, or ‘the black ink, the red ink’ which was the way the Mexica (Aztecs) and other Mesoamerican speakers of Nahuatl described knowledge, wisdom or understanding, especially of the kind that comes from learning the colored-ink pictographic records kept in the houses of learning. This interpretation of Lezama’s allegory means that the central red and black pair, in their painted nudity, signify knowledge perhaps as a kind of immersion in the bath – a knowledge that is fully corporeal, communal, and passed from one generation to the next.

The concept of a nude immersion as a coming-into-being, like a baptism, gets a powerful treatment in Lezama’s painting El árbol nodriza [The nursing tree], which presents many of his recurring motifs, including body-painted nudes among both natural nudes and clothed figures. Body-painted nudes in Lezama’s works can be considered as a kind of meta-canvas, or a painted canvas within the painted canvas, and in El árbol nodriza we see the act of painting linked to giving birth and to giving sustenance.

The central two-headed woman gives birth into a round container in which some of the babies are green (female), some red (male). Everything is connected beneath the tree: branches extend into the paint, men implanted in the crop rows suckle at fruits hanging from the tree, the shadow woman’s right hand grasps a tree root, the necklace-wearing woman grasps the braids of the woman giving birth, and her necklace is pulled by the boy, whose red shadow jointly holds a mushroom with the woman’s black shadow. The two of them reiterate the red and black knowledge embodiment from the bath painting, but with the colors reversed. The entire canvas shows the cycle of human life and death, and plant growth and decay as well; in this way, it extends and develops the original imagery of the chichihuacuauhco, Nahuatl for ‘tree of breasts,’ that awaited, in the afterlife, those who died in infancy. As depicted and explained in the Codex Vaticanus, these infant souls were nourished by the chichihuacuauhco and would someday be reborn into the human realm.

In so many of his works, Lezama uses nudity, whether natural or body-painted, to emphasize the lived immediacy of symbolic meanings throughout our lifespans. His nude figures embody transformative moments such as birth, puberty, old age, and death, even as they resuscitate ancient Indigenous beliefs through re-interpretations of their corresponding iconography. 🪐

Thanks for sharing about Daniel Lezama's work. His symbolism partnered with the nudity drew me to his paintings a couple of years ago. I enjoy his and Felix D’Eon's art partly because as Mexican Americans they instill a touch of a different culture into their art which gives the viewer the ability to see or become aware of something through a different lens. Hope you don't mind if I copy this writing to save as background information on Lezama.