Spencer Tunick's Naked World

Review of the 2003 HBO documentary following Tunick’s first global installation tour

It was during the writing of my recent review for Naked States, about a young Spencer Tunick setting out on a cross-country journey to photograph nudes in every state, that I learned director Arlene Nelson made two additional documentaries about Tunick and his work. I quickly found a copy of Naked World, released just a few years after Naked States, and watched it to see how his work developed and changed in that short time.

Naked World opens not unlike Naked States, showing Tunick getting arrested yet again during a shoot in New York. Where that hung over him for the majority of Naked States, we move past it quite quickly here to the real focus of this documentary. Tunick’s next big project is a world tour, attempting to photograph nudes on every continent. An undertaking like this requires more resources, and it’s made clear pretty quickly that by this point in time (2001 by my estimation, a year after the release of Naked States), Tunick has made a name for himself and become more established in the fine art world, collaborating with museums and governments in order to make this ambition of his a reality.

This is made clear in his first stop: Tunick goes to Montreal to shoot over 2000 nudes nearby the Museum of Contemporary Art. This shoot was organized with the Museum’s assistance, as well as the local government. Tunick even comments as he speaks to the crowd of models about how happy he is to know that he’s not going to get arrested on this day. We do get to see a little bit of that manic apprehension he displayed so much in Naked States, but not nearly as much. It’s also stated that this is his first time shooting such a huge group in color; every shot he makes in this project is in full color, contrasting with the black and white shots he took for Naked States.

He moves on to Paris for the next part of the project, where surprisingly he has no support. We see him running around asking strangers to model and getting turned down. Some locals talk about how while nudity in art is fine, nudity in public is still considered wrong. Deflated, Tunick turns to the internet to find a model for an Eiffel Tower shot he wants to do. An attempt to shoot at the Louvre is also interrupted by security guards with dogs. “Something about Paris, they want to attack the naked people,” he says in frustration.

Tunick was approached by members of the Tate Museum to shoot in London next. Even with their help, he’s approaching strangers with flyers on the streets in order to find models, but his shoot at the Cutty Sark goes well, and we get a nice quote about why Tunick is so driven to shoot large crowds of bodies: “I always like to think of the bodies as water, the bodies forming waves and ripples.” It reminds me that our bodies are mostly water, roughly 60%. From there, Tunick and his team travel to Dublin, where he once again has no support and seeks out individuals to model. A priest and others are interviewed about Catholicism’s grip on the country and how things are changing, a cultural insight that will become more of an ongoing thing for the rest of the documentary.

St. Petersburg, Russia is next. While Tunick spends time with some museum curators here, he’s once again shooting individuals on the fly. It’s here where he has to clarify the nature of his work more than ever before, and unlike in Naked States, this is where I realized we see him interacting more with the models themselves in this film. Throughout, we get to see him taking their hands and helping them up, grabbing their clothes, hugging and shaking hands after successful shoots, and it’s very sweet. I mentioned in my review of Naked States how the affect his work has on his models doesn’t seem to register much to him at all, but here you can tell he knows it. “I’ve always loved contemporary art and have dreamed of participating in it somehow,” one of his Russian models states. “Art is freedom. That’s freedom for me. It’s the most important thing in my life.” This is something that I quietly hope for others to feel when I draw or paint them, for my work and their involvement in its creation to mean something to them.

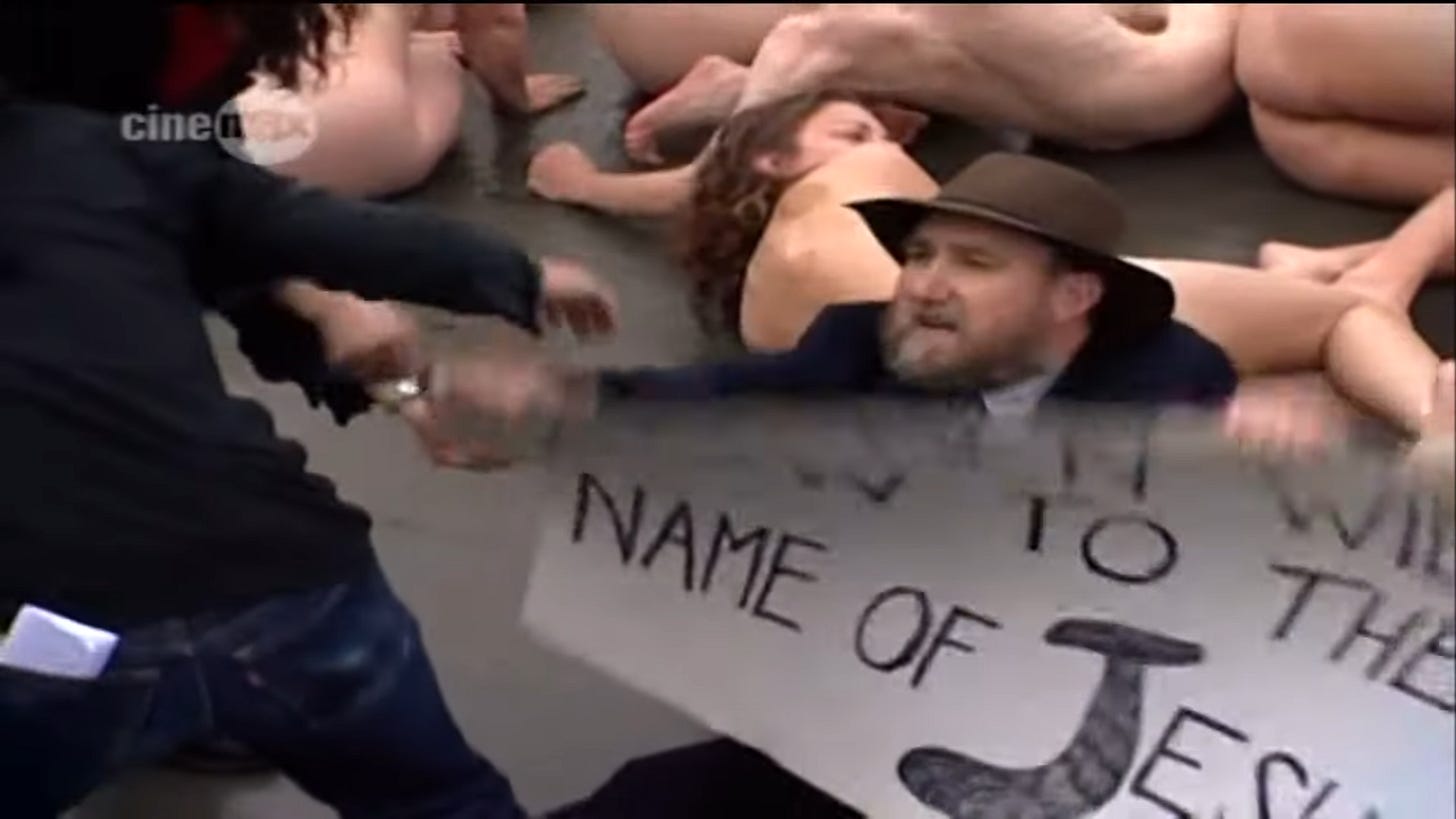

The next big installation shoot happens in Melbourne, Australia, for the Fringe Festival. Now that he’s more well known, it’s funny to get to hear what folks have to say about Tunick. One man is pretty critical of him, but then immediately states afterwards that he’ll be going to model for this shoot. This is the first time we see the weather actually cause issues, but the skies eventually clear and a new problem presents itself in the form of a protester running up to the group of bodies with signs as he repeatedly shouts “all men will bow to the name of Jesus Christ.” Police and assistants quickly remove him and one of Tunick’s most iconic shots is taken. I do wonder if anything like this has happened at other shoots of his. There’s also an interview with an HIV positive woman speaking about the shoot and what it meant for her that’s truly moving. We later see her with another model who’s gripped with emotion, and it’s a beautiful little moment of connection.

It’s interesting to see how Tunick and the nature of his work draws marginalized people. His Japanese models in the next segment discuss how in the corporate culture there, modeling nude would be unheard of, it’d cost you your job if your boss found out. One woman quietly states: “I do feel that I’m different from other people, but I don’t think it’s a good thing to tell other people that I’m different,” which broke my heart. When Tunick goes to Cape Town’s District 6 in South Africa, models openly discuss the Apartheid and how they are viewed. One of his models is a 73 year old political poet who mentions having been arrested in the 1970s. He reads from one of his poems about freedom, and talks about how incredible it is to get to model at his age, to keep surprising people. “I’m taking off my clothes and looking into the future, naked as I am.” This is the one place where Tunick’s work feels truly political in a way it hasn’t to me.

Antarctica is a surprising next stop, but Tunick did state he wanted to shoot nudes on all seven continents, didn’t he? His partner Kristen Bowler models for the first time here, posing with penguins, and another older model discusses stripping off in the cold and revealing the scars from where she had been severely burned as a two year old.

The project’s final stop is in São Paulo, Brazil. Tunick was approached to exhibit for the 25th Le Bienal and we see the show being set up before he sets out to do his final installation shoot for the project. These huge installations cannot happen on their own, with one person. Tunick needs to collaborate with museums and galleries, with local governments, to make these things happen, and it’s kind of awe inspiring to see how it all comes together. It’s a very different vibe from the small team he had traveling together in a van for Naked States. To see someone get the resources they need to execute such a large scale project is incredible, but…not exactly relatable for me. I will never get to achieve something like this as a watercolor painter, but that’s okay. I don’t need to.

All in all I enjoyed this much more than Naked States. Everything I found lacking in that documentary is more on display here, and the movement from one culture to the next was really fascinating. The copy I watched was a CineMax rip that I found on Youtube, with Spanish subtitles you can’t get rid of, and there seem to be other, sketchier places to watch it online as well. It seems the documentary got a DVD release, but it’s only available in the secondhand market. Again, like with Naked States, this was produced by HBO, so why it doesn’t seem to be available on HBO Max is beyond me. 🪐