Nudist or naturist: An age-old question

Can naked sages in ancient times help us work out the difference between naturism and nudism?

Editor’s note: This article was previously published in Naturist Life magazine and is republished here with permission of the author, Nick Mayhew-Smith.

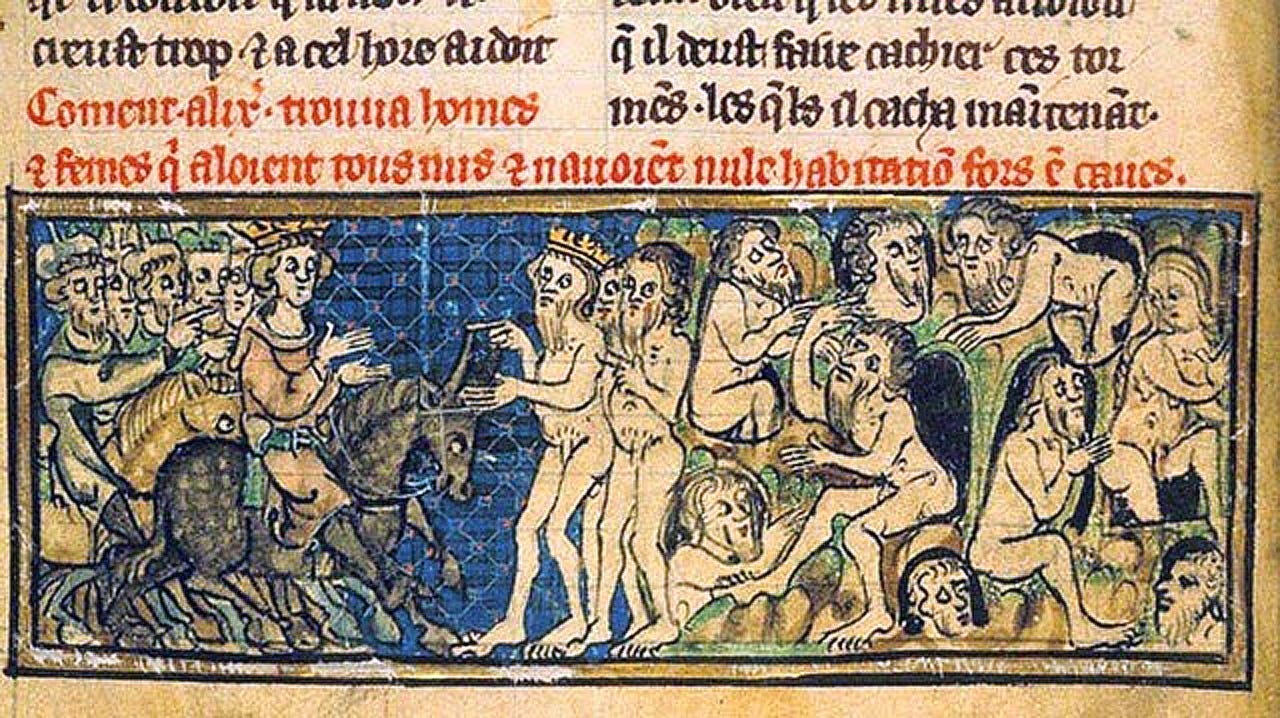

Let me tell you about the time Alexander the Great met some nudists. Back in the 4th century BC, the Macedonian king was travelling on the eastern fringes of his empire when he captured a group of sages, who were advisers to one of his enemies. History records that these sages chose to live permanently naked as a matter of principle. In ancient Greek they were called gymnosophists, which translates as naked philosophers.

The sages believed clothes were a distraction to clear thinking, and their stripped-down lifestyle also included strict vegetarianism and earnest contemplation about moral behaviour.1

Alexander the Great posed these philosophers a series of questions and was sufficiently impressed by their wisdom he decided to set them free. The questions were along the lines of:

“How can a man become a god?”

To which they replied: “By doing something no man can do.”

Short and pithy, as one might expect from a group of people so earnest in living the simple life. Alas the sages never had a chance to answer our very modern conundrum about a naked way of life: “What is the difference between a nudist and a naturist?”

It is a question that will send many of today’s naturists running for the hills, claiming it is nothing more than an exercise in splitting hairs. But I think it is of vital importance. To my mind, our inability to answer such a basic question does naturism a disservice, and hinders our attempts to explain ourselves to the general public.

More to the point, it fails to explain what we should call these ancient gymnosophists. Can they be called nudists? Well, Yes. They are men, and possibly women, who went out of their way to live without clothes. It doesn’t really need anything more complicated than that.

Nudists are people who avoid wearing clothes in situations where others do. Even in a culture where tasks such as exercise or bathing were commonly performed naked, Alexander and his Greek friends thought the ‘naked philosophers’’ nudity was the most remarkable thing about them. They could perhaps have called them ‘vegetarian philosophers’, but they didn’t, their nudity was what stood out the most.

Living naked full-time is as pure an expression of nudism as you are likely to find. For the gymnosophists, it was backed up by a fully formed philosophical rationale about avoiding worldly comforts and distractions. They weren’t simply naked for the sake of it, but as part of a carefully developed outlook on life. If you choose to do something that is unusual, people will ask you why. It is helpful to have an answer ready.

These naked thinkers were not just a one-off aberration. Other unclad communities of people who deliberately practised nudity stand out just as starkly if you dig through the historical records.

Ways to go naked

In recent articles for Naturist Life and British Naturism magazines, I wrote about a nameless, 4th-century Christian hermit who lived without clothes on the flanks of Mount Sinai for 50 years. He was much admired by the early church for his single-minded dedication to solitude.

His nudism arose from a very different place to that of the Greek gymnosophists, although like them he had a good explanation for it: by casting off all the trappings of civilisation, including clothes, he was making it known that he wanted to be alone. His nudism therefore rests on the notion that nudity is inherently anti-social. I was so surprised to discover that there were such long-term nudists in early church history I titled my recent book The Naked Hermit in his honour.2

And indeed this naked hermit was not the only one of his kind, and nor was this practice confined to men only. It was a minority pursuit for sure, but those who practised the discipline of very long-term nudism were greatly revered by early Christians.

St Mary of Egypt is still celebrated by the church today, another desert hermit who is said to have gone naked in the Jordanian desert for decades.3 She tried to cover herself when she finally bumped into another hermit in the desert, because again her nudity was a symbol of strict solitude.

Moving on, we can find another use of deliberate nudity in a spiritual context much closer to home, in 17th-century Britain. The early Quakers and their close cousins, the Ranters, were well known for running down the street naked as a protest against rigid social hierarchies and restrictions on how they could worship. A contemporary image shows a group of such Quakers standing naked in front of a bemused onlooker, with the caption ‘Above ordinances’, a sarcastic way of saying they thought they were above the law.

A lesson we can take from that is that we naturists are not the first to be mocked for our deliberate nudity and no doubt we won’t be the last.

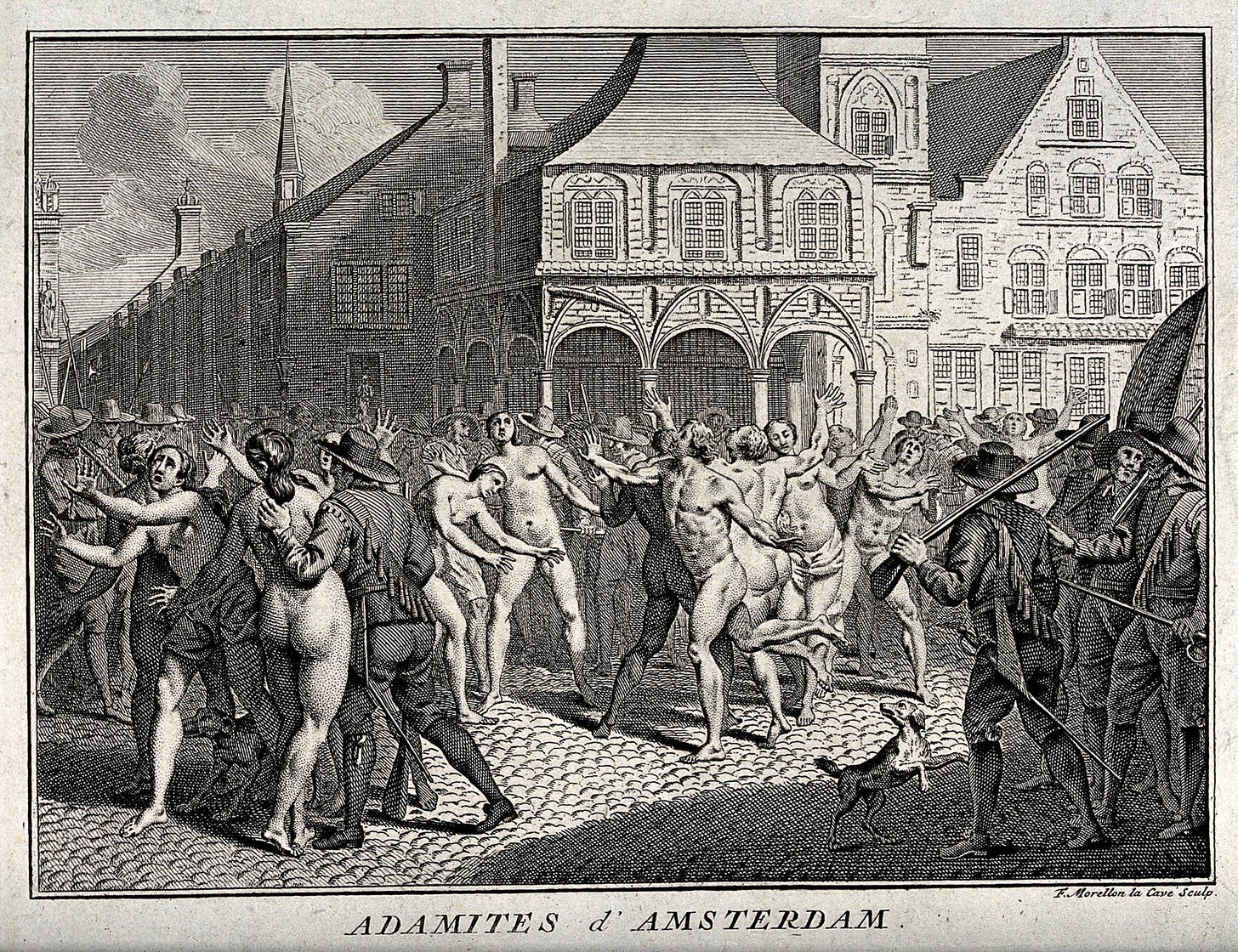

Another image shows some Neo-Adamites protesting in Amsterdam, men and women being arrested in a public square for their dedication to the nudist cause; an image of prejudice that we naturists do well to remember.

This form of nudism is essentially a rejection of society’s norms, of the social contract that binds us to the authority of the state. For this reason dissenting groups such as the Quakers were known by the term 'non-conformist'. As a form of protest this public nudity has obvious parallels with today, as in the naked bike rides. You might also have heard of the academic Dr. Victoria Bateman, an economist at Cambridge University, who has used nudity to express her dissatisfaction with contemporary politics, and Brexit in particular. It is clear that Dr Bateman is not promoting or expounding naturism as such through her nude activism, but rather rejecting social and political norms. She’s certainly sympathetic to naturism, as are many participants on the naked bike rides, but there are mixed motivations behind those protests that do not all amount to naturism as we understand it.

There are many other forms of deliberate and sustained nudity being used in a wide range of contexts, but I will finish with one modern example where nakedness is used as part of an outdoor ritual; communing with the natural world. Modern Neo-Pagan ceremonies, such as Wiccan, often incorporate some form of magical circle in which participants go 'skyclad' or naked at night. The reasons for this are again many and varied and indeed some claim the custom has been inspired by an Indian philosophy related to those Greek gymnosophists we met earlier. Some devotees also claim that they are not truly naked but are instead ‘wearing’ the natural environment, dressed in the sky.

A lot of the early adherents of the Neo-Pagan revival in the 20th century were also naturists, as it happens, but by no means all of them. At an academic conference on New Age spirituality, recently, I met a Wicca practitioner who described the nudity as a matter of strict ritual necessity and argued that the movement should minimize it as far as possible because it made them look eccentric and trivial.

In a non-spiritual expression of this same impulse towards the environment, television presenter Kate Humble has spoken of her joy of dancing naked outdoors, something that she does in the wilderness as a way of getting closer to nature. In an episode of BBC Two's Off the Beaten Track she skinny-dipped in a Welsh mountain lake with artist Natasha Brooks, and received mostly glowing plaudits for doing so.4 You can see and hear Humble’s reactions on a YouTube video.5

What is nudism?

Having described the many ways people have chosen to go naked, I can think of only one word that encapsulates all of them: nudists. By consciously deciding to go naked where others would expect to be covered, they are deliberately practising or embracing nudity.

There are many reasons that drive them to do this. Some are profoundly philosophical, others deeply spiritual, some are anarchistic while others are the opposite, very gentle and in tune with nature. It is nice to think that the experience of being naked can mean so much to so many people, and has created such a rich culture over the whole of human history. This is our heritage, and we would do well to embrace it, celebrate the millions of men and women who have put their bodies (some literally) on the line to keep the nudist flame burning. Indeed, three of the world's great religions, Judaism, Christianity and Islam, record the start of human existence with a pair of nudists: Adam and Eve.

What I would like to stress is that nudism is an integral part of the human story, stretching back to some of our earliest written records and some of the earliest artworks too. People have deliberately chosen to take off their clothes outdoors, in public, driven by deliberate, ethical, passionate and coherent reasons for doing so. Nudism, therefore, is an enduring part of human culture. It always has been and it always will be.

I think this is something we would do well to remember when we try to explain what we are to a sceptical textile society, taking pride in the fact that nudism has been and still is an essential and long-standing part of the human story. That it has something positive to say about our nakedness in so many contexts. The naturist movement is a modern and highly successful chapter arising from this nudist heritage.

What is naturism?

But why not call all of these many naked pioneers ‘naturists’? Well, the answer becomes pretty obvious when looking at the very mixed reasons that have been given for living clothes free through the millennia.

Take the naked hermit, living on the flanks of Mount Sinai. For him, nudity was the embodiment of rejecting society, and therefore rests on the notion that the naked body is anti-social. He would never agree to living naked in the company of others, and indeed was said to run away if anyone came near him. If nudity is seen as a way of keeping other humans at bay, it stems from a fundamentally different place to modern-day naturism. We believe in and practice a form of nudism that is essentially communal, where men and women socialise freely and equally in the nude. This notion that nudism is inherently anti-social still lingers today, but is now mostly expressed by those who are opposed to public nudity.

Other nudists we have met had very different reasons again for their deliberate nudity. Far from avoiding the public gaze, the Ranters, Quakers and Neo-Adamites positively revelled in running down the street, disrupting the status quo and trying to shake people out of their complacency. For them nudity was subversive, and highly political.

Yet another expression of nudism that is different to modern naturism is found in the naked sages that Alexander met. They considered themselves to be a class apart, an elite reserved only for those who met their intellectual, physical and dietary requirements. Naturism today doesn't have such strictures, and indeed these strict nudist gymnosophers would no doubt frown on such ideas as sunbathing, holiday resorts and naked leisure generally.

So in summary, all these nudist cultures may have one very obvious thing in common with modern-day naturists, but there are also differences and nuances that run far deeper. We are all nudists, but nudism is a very wide and general term that encompasses many beliefs and practices. Naturism is a subset of the very diverse and enduring universe of nudism, a type of nudism that sits alongside many other nudist movements.

A modern-day naturist might well agree with and participate in some of the other expressions of nudism I’ve outlined, but not all of them because they are so different and in some cases mutually exclusive. I have never heard a naturist argue that nudity must only be practised in absolute isolation, for example, or confined to a brief moonlit ritual.

I am passionate about my naturism, and take huge pride and satisfaction in fitting it into this bigger vista of what the naked human body has managed to represent over the millennia; connecting it to so many rich and varied expressions of that wonderful nudist impulse. When we compare our naturism to the nudists of old we can see that there is much more to nudity than simply getting undressed. 🪐

A modern dictionary definition of gymnosophists is: ‘a member of an ancient Hindu sect wearing little clothing and devoting to contemplation.’

Nick, Thank you for your article. There is a spectrum of behaviors over the eons that have included social nakedness (See 1996 "N" 15.3 113-124). Each person has their own level of comfort and acceptance of when being clothes free is best. Hygiene is linked to bathing in water and heat. Spiritual practices are linked to removing oneself from the material work as well as accessing its natural attributes be they rain, moonlight, tellurian currents, negative ions or other stated values. Mental and cultural practices are linked to protests and confronting the current norms of society. There are also the pleasure seekers such as the hedonists, Bohemians, swingers and now lifestylers.

Cec Cinder's "The Nudist Idea" documents the factors that came together in the late 19th century to become the definition of nudism with its absence of clothing, alcohol, tobacco, animal flesh, and pornography, while engaging in regimented physical exercise. It became a community of health minded individuals, however it was restrictive to physical places. The Naturists wanted to focus on the social nakedness aspects but in public areas to promote general body acceptance and fostering self-esteem. You are correct that hours of discussions and gallons of ink have not resolved a strict definition between nudism and naturism, but knowing the history from whence we have come, is foundational to knowing how to describe who we are. Thank you for this informative background.

If you want to know more about the Gymnosophists, I have written the only available book on the topic, Seekers of the Naked Truth: Collected Writings on the Gymnosophists and Related Shramana Religions. The last time someone did that was in 1665. And despite the definition in the article, they were certainly not Hindus. I have also written a film script on the topic, Seekers of the Naked Truth, available in the second expanded edition of my book, Naturist Writings of Paul LeValley, Including Movie Reviews. Both are available from my web site, paullevalley.com/books, or at higher prices on Amazon.