‘FKK in der DDR’: East Germany’s socialist nudism

The story of how one country nationalized nakedness

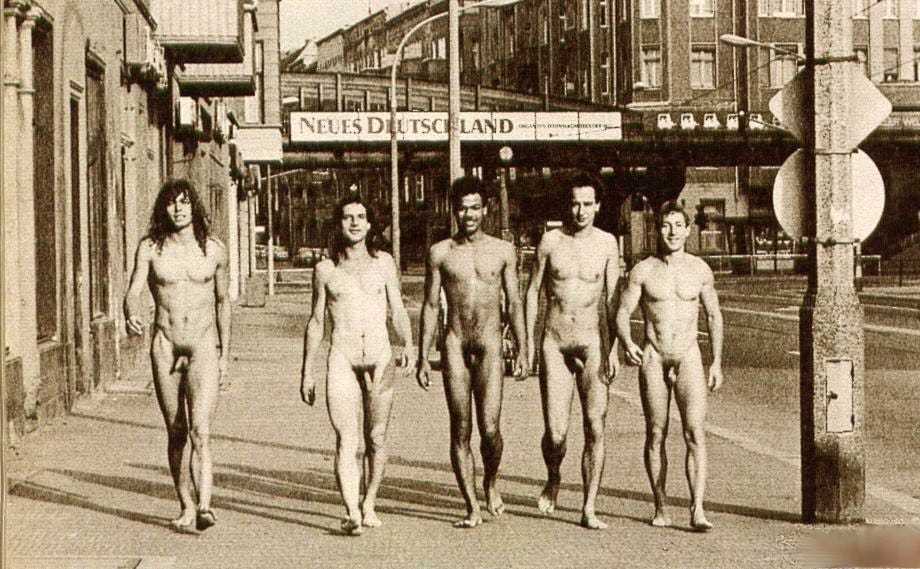

Thousands of red banners and German tri-color flags fluttered in the warm breeze on July 4, 1987 as columns of people snaked their way through the streets of Berlin. Citizen participants proudly showed off the latest economic achievements of the factories and farms where they worked. Actors and dancers performed elaborate spectacles. Soldiers from the National People’s Army demonstrated their determination to defend the country from capitalist incursion.

It was a scene not so different from the many parades and processions held in the Eastern Bloc countries during the Cold War years. The occasion this time was the 750th birthday of Berlin, capital of the “workers’ and peasants’ state”—the German Democratic Republic, or East Germany, as many knew it.

This particular parade featured one group of revelers, however, that set it apart from not only the staid, gray image of communism that Western propaganda tried to paint but also distinguished it from all other state-sponsored events held anywhere on Earth in modern times.

Going right down the center of Karl-Marx-Allee was a float totally unlike the others belonging to various sporting clubs and recreational groups. Atop it, surrounded by fishing poles, nets, and other tackle, sat a couple of beaming bare-breasted women in lawn chairs. The cameras didn’t shy away, nor did Erich Honecker, leader of the GDR. Viewers watched on their televisions at home as the Chairman of the State Council waved and smiled at the sunbathers.

A few weeks later, a river parade was staged in the suburbs as part of the same anniversary festivities. There, a boat carrying dozens of naked men and women and a sign reading “FKK-Anhänger aus Rahnsdorf,” “Nudists of Rahnsdorf,” motored past the East German officialdom, once more earning cheers.

Such scenes may seem unthinkable, given the prudishness and restrictive instincts of most governments, but East Germans weren’t the least bit shocked by their politicians’ reactions. That’s because they’d grown up in a society where nudity was normalized and body shame was officially discouraged.

Survey data collected in 1990, just months before the GDR disappeared, showed that 68% of apprentices between the ages of 16 and 18 had swum in the nude; for young workers in their 20s and 30s, it was 81%; and among students, the number hit 87%.1 Baden ohne, or “bathing without” in German, was a pastime that had grown in popularity with each new generation in the GDR.

Germany is, of course, widely known as the birthplace of modern nudism, of freikörperkultur (free body culture, or FKK). It’s a tradition that has carried through from its roots in the late 19th century lebesnreform (life-reform) movements on up to the present day. But it was in the GDR that FKK, in many ways, reached its pinnacle. East Germany no longer exists, but the persistence of German naturism owes a lot to the fact that it did.

Though initially suppressed after the GDR’s founding in 1949, by the 1970s and ’80s, grassroots nude culture gained official endorsement as a socialist antidote to the commercialized sexuality of capitalism. It became a supplement to the state’s Marxist ideology. As an exhibit in the DDR Museum in Berlin today states, for many East German communists, “nakedness was an expression of classlessness.”2

Years after the reunification of Germany, public nudity remains a faultline between the country’s two halves. It is a fading hallmark of “ostalgie,” the “East nostalgia” embraced by those who miss life under socialism.3 While the society that existed on the eastern side of the Berlin Wall was undeniably authoritarian in many respects, the “people’s nudism” that flourished there contained a liberatory potential that is still worthy of study today.

Proletarian nudism before the war

From its start, nudism in the GDR was a populist affair, a trend that the people themselves developed and forced the state to recognize. Rising from the ruins of World War II, the government established in the Soviet Occupation Zone was eager to make a fresh start, to show it was unbound by Germany’s imperialist and fascist pasts. There was one old tradition, however, which proved difficult to extinguish, especially because its historical lineage was intertwined with the socialist ideology embraced by the new state.

Freikörperkultur, the original modern nudist movement, had eclectic origins, with links to healthier living fads, middle class reformism, vegetarianism, conservationism, critiques of industrialization and urbanism, as well as eugenics and right-wing nationalism.4 It also possessed a strong socialist and egalitarian element, however, whose adherents actually constituted the majority of German nudists in the 1920s.5

In that decade, educator and Social Democratic Party activist Adolf Koch established his Physical Culture School, which fused nude exercise, gymnastics, heliotheraphy, and other practices into a popular all-around health regimen aimed at workers and their families.6 It’s a tradition that partially survives in Germany today in the form of the Family Sports Club-Adolf Koch, which promotes “Nacktsport und Body Positivity.”7

Around the same time Koch was establishing his school, the socialist “Friends of Nature Tourist Association” (Naturfreunde) offered working-class Germans the opportunity to join in nude hiking expeditions and recuperate from the drudgery and unhealthy work conditions of urban capitalist factories.8

Historian John Alexander Williams argues that these early socialist nudists conceived of the worker’s body, male and female, “as a symbol of the health of the working class.” He says that the connection of nudism and health became “a metaphor for the potential of industrial workers to take hold of their own fate collectively.” Physical and mental exploitation in the workplace, repetitive labor, poverty, malnutrition, poor housing and sanitation, bad lifestyle habits, religious manipulation, sexual repression, shame—all contributed to the dehumanization of the working class.

Koch diagnosed capitalism as the primary illness afflicting working people and prescribed a nude fitness regimen as part of the treatment:

“We exercise in the nude because we can clearly recognize in the body the damages brought by contemporary life. Sagging breast, hanging shoulders, and bad posture are imperfections. The cultural-political work of exercise begins here, and here we should ask the questions, ‘Why have I become so? Are the workplace and apartment, or my own way of life, at fault? Does not my pale, anemic complexion reflect the fact that state welfare and health insurance institutions only intervene when sickness is obvious? Does not bad or impractical nutrition also play a role? Can we fight the political and economic fight when our bodies are weakened?’”9

The socioeconomic system and the denial of scientific education also infected the proletariat with a mentally damaging view of their own bodies and sexuality, Koch argued. Shame, he said, was “an artificial feeling of inferiority” imposed on the minds of the people by the ruling class and its ideological supporters in the church and state. Those in power counted on workers’ “stupidity” to reinforce “the emotional anchoring of bourgeois morality.”10

Liberating the body, the socialist nudists reasoned, would help “ennoble the mind and raise political consciousness.” Their goal: “Restore the body, the worker’s only real capital,” and thus begin the work of creating new human beings to carry the country toward “a just, democratic, and socialist future.”11 Richard Bergner, one of the ideologists of the movement, declared: “Out there in nature, we will get rid of our last constraints—our clothing—and let air and sun work upon our naked bodies…. Air and sun are the worst enemies of proletarian sickness.”12

Such ideas were not unique to Germany. Radicals elsewhere in this era were arriving at similar conclusions, convinced of the revolutionary potential of nudist practice.

No less a figure than Lenin himself recognized the congruity between communist thought and social nudism. He believed that in a state of nakedness a person’s class origins were largely obscured, allowing people to finally treat one other like equal human beings. Lenin had visited Germany and was impressed by its nude beaches; he returned to Russia criticizing those “who coyly insist on the need for a fig leaf.”13

In the Soviet Union that he founded, the Down With Shame (Долой стыд) movement embraced nudism as a symbol of the new society being built after the Russian Revolution. “We have destroyed the sense of shame!” their banners declared. “Look at us and you will see free men and women, true proletarians who have thrown off the shackles and symbols of bourgeois prejudices!” It was reported that 10,000 of the shameless marched through Moscow’s Red Square in the early 1920s before their movement was suppressed during the Stalin years.

In the United States, sociologist Maurice Parmelee, author of the landmark 1927 text The New Gymnosophy, also concluded that “communistic ideas” were highly influential in the nudist movement. “The universal or widespread practice of nudity would involve the obliteration to a large extent of class and caste distinctions,” he wrote. “It would mean more democracy and individual freedom through the disappearance of many oppressive conventional, moral, and legal restrictions.”14 Like many other nude advocates of his day, Parmelee was influenced in his views by repeat visits to Germany and the experiences he had with its nacktkultur.

But Germany’s status as the hub of world nudism, and especially of socialist nudism, ended abruptly after 1933. The dictatorship of Adolf Hitler mercilessly crushed all civil society organizations, including the FKK societies. On March 3, 1933, just five weeks after the Nazis came to power, Hermann Göring issued a decree abolishing the “naked culture movement,” saying it “deadens women’s natural feelings of shame and kills men’s respect for women.” It was also said to encourage homosexuality.15

With liberalism and Marxism both verboten, reactionary gender, sexual, and moral norms were rapidly imposed. Despite this, the naked body remained a regular feature of Nazi art and propaganda—an Aryan ideal of perfection supposedly worthy of aspiration by young men training for war or young maidens preparing for motherhood. In statues, films, paintings, and more, the nude form was ubiquitous.16

With the Social Democrats, Communists, and trade unionists eventually either forced into exile, silenced, or shipped off to the concentration camps along with the Jewish population of Europe, Hitler’s Germany eventually allowed the remnants of the conservative bourgeois nudist movement to step back into the sun.

A few nudist associations were given permission to operate under the umbrella of the government-sanctioned “League for Body Discipline.” An SS major and old-time naturist, Hans Surén, had convinced some of his superiors that, given appropriate supervision, nudism could help produce stronger and healthier Germans, assisting in the goal of breeding a superior race to conquer the world for fascism. In 1942, laws were adjusted to allow nude bathing, but only in places where unsuspecting third parties were unlikely to stumble upon it.17

The lifespan of this racist and restricted form of Nazi nudism was short, however. As the Allies closed in on Germany, the war effort consumed more and more of the country’s people and resources, leaving little time for recreation. By spring 1945, Hitler was dead, and Germany was split among the victors, with the U.S., Britain, and France jointly occupying the west and the Soviet Union controlling the east.

The 1946 elections in the eastern zone were won by the Socialist Unity Party (Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands, SED)—a merger of the old Social Democratic Party and the Communist Party of Germany. In the western zone, the Western Allies continued to rule directly for awhile before eventually re-establishing a party and electoral system. The two halves of the country were put on diverging political paths.

Intended to be temporary, the hardening economic, ideological, and military confrontations of the Cold War quickly made the partition permanent. In May 1949, the Federal Republic of Germany was formed in the western zone, and a few months later, on October 7, 1949, the German Democratic Republic was established in the east under SED rule, and much of the economy was nationalized.

Protect the eyes of the nation

The new SED government was determined to erase all vestiges of the old Germany—the Germany of the Kaiser and of Hitler. This steadfast commitment to creating a new society modeled on the Soviet example made officials suspicious anytime reminders of the old order popped up; the re-emergence of FKK was no exception.

The spontaneous re-establishment of some of the pre-war nudist organizations and naked bathing spots alarmed authorities. In some areas, particularly along the Baltic Sea coast, they tolerated nude swimming as an individual or family activity, and official beaches were even established for the purpose.18 As more Germans began rushing to the FKK zones, however, SED bureaucrats became paranoid that there might be efforts to form nudist clubs independent of the state. Johannes Becher, minister for culture, implored his comrades in the cabinet to “protect the eyes of the nation” from the threat of nakedness.

In 1954, Interior Minister Willi Stoph answered the call, declaring nude bathing had “no legal foundation,” despite the fact that the Nazis’ 1942 ordinance was actually still law. Regardless, all sorts of claims were made by Berlin officials about the supposed obscenity and sexualization that allegedly happened on nude beaches. They warned of the dangers to children and even claimed nudists were stripping other visitors and throwing them into the sea. Nude beaches were not technically made illegal, but bathers were informed that they could only enjoy their pastime in areas where no one else could see them and that no signs or fences were allowed to indicate a nude zone. With no means of preventing unsuspecting clothed bathers from wandering into nude areas, the restrictions amounted to a de facto ban.

Josie McLellan, who has chronicled the lost history of the GDR’s sexual revolution, observes that the government’s moral panic often deployed Marxist language in an attempt to legitimize repressing FKK. It portrayed nudists as bourgeois intellectuals and diletantes, damning charges in an anti-capitalist society. She quotes one internal government report which called nudist organizations “a product of the disintegration of imperialism in the area of body culture and sport…an expression of imperialist decadence which cannot be tolerated.”19 The authors of the report pointed to the racist blackface “Cameroon parties” that a minority of nude bathers engaged in on the Baltic coast to paint all naturists as Nazi sympathizers and a danger to the racial equality and anti-colonial solidarity promoted by socialist ideology.

The GDR leaders who stoked the anti-nudist fires had spent much of the Nazi period in exile living in the USSR, where Stalin’s turn toward social conservatism in the 1930s had outlawed nudism, abortion, and homosexuality and restricted divorce rights. Several top communist officials’ notions of what constituted acceptable public behavior and morality had traveled quite some distance from the left-libertarian spirit that defined 1920s German radicalism.

The hype around the threat of nude recreation made little headway among the majority of Germans, however, many of whom had memories of the egalitarian and anti-fascist nudism of the interwar years. No sooner was the ban on nude swimming being enforced than they began challenging it. Signs forbidding FKK at beaches repeatedly disappeared or were vandalized. Hundreds swam nude despite orders not to do so, or they wore some small item of clothing like a necktie to ridicule the regulations. Among those arrested were often dozens of local public officials, highlighting a disparity of views among the state’s own personnel.

Letters flooded into the Ministry of the Interior berating the government for abandoning its own progressive heritage. Petitions pointed out the hypocrisy of a state that proclaimed its intention to lead Germany toward freedom and democracy while suppressing the most fundamental of liberties.

Also likely shocking to the SED was the large number of its own members who were among those submitting complaints. In their missives, rank-and-file communists compared the actions of GDR police to the Nazis who had attacked nudists years before. One local SED group near Berlin told Stoph, “Nudism is an integral part of the [communist] party, an old tradition.” They even reminded him that “our Soviet friends also practice nudism.”20

After two summers of flailing enforcement efforts, the state admitted defeat. In the spring of 1956, a new ordinance was issued overriding the 1942 Nazi law as well as the 1954 ban. Local authorities were granted authority to officially designate beaches for nude swimming, to place signs indicating them as FKK zones, and to allocate funds for their maintenance.

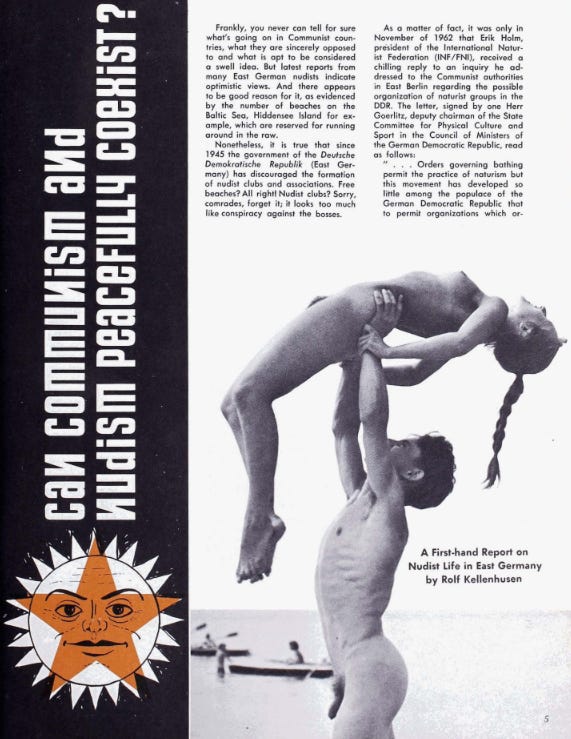

Independent nudist organizations were still not allowed, though.21 The Interior Ministry decreed that it was “forbidden to form societies which organize, promote, or propagate nudism.”22 When International Naturist Federation President Erik Holm inquired with GDR authorities about setting up an affiliate in the country, he received a reply from the State Committee for Physical Culture and Sport saying that the practice of naturism was “so little developed” among the population that “it is neither justified nor necessary to permit” nudist advocacy groups.23 The door was left open, however, for establishing nudist “sections” of existing sport and recreational associations.24

While some party leaders still preferred to pretend nudism was of interest to only a marginal minority, East Germans themselves soon proved otherwise. They had won the right to go naked and began stripping down in increasing numbers, leaving the state to catch up with them.

The naked vanguard

Other factors also played a role in shaping developments. As tensions between the U.S. and the USSR rose and the East German economy struggled with steady outward emigration, the Berlin Wall went up in 1961, a cement symbol of Germany’s division. Facing a future cut off from their compatriots in the west, the government and people of the GDR turned more resolutely toward building a new life amid the rubble they had inherited from fascism.

As the economy recovered in the late 1950s and early ’60s and housing and other costs became cheaper, GDR citizens found themselves with extra money to travel for pleasure. Seaside trips to the Baltic Coast were a popular way to spend a holiday, especially since such vacations were usually subsidized by trade unions or state employers.

Victor Grossman, an American who lived in East Germany after defecting in 1952, said that unions “like the miners or steel workers had their own hotels, but every factory or office had a supply of two-week vacation tickets to divide up among employees, most of them for an incredibly low 30 marks, including bed, all meals, evening dances, programs of music or talks about local history, and a morning half-hour of beach calisthenics for those who wanted it…. Union hotels in the mountains or at a lake could be enjoyable, but the shores of the Baltic were always in greatest demand.”25

As the number of tourists grew, so too did expectations for nude recreation space at the beaches. Nude bathers multiplied to such an extent that the FKK zones began creeping closer and closer to clothed, or textile, beaches, meaning they were no longer isolated stretches of sand far from public view. Increasingly, nude and clothed bathers were all mixed together on the same waterfronts, regulations be damned.

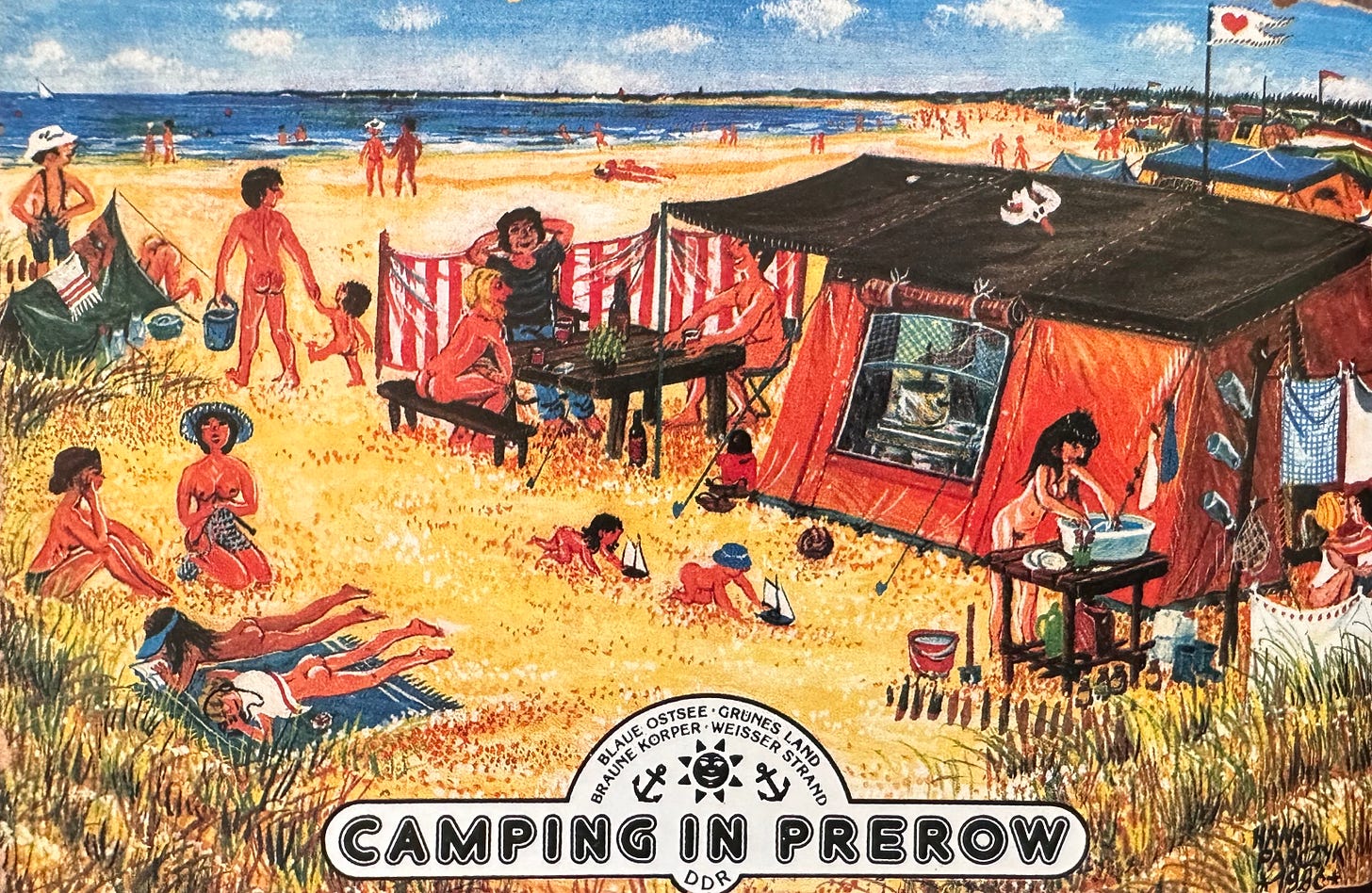

This development was helped along by further nudist civil disobedience, which had continued after the success in overturning the 1954 ban. In the town of Prerow, police efforts to fence in and separate the nude beach failed, as unclothed citizens moved the signs and cordons themselves, tripling the size of the nude zone. They also established an unlawful nude camping area; police tolerated it, largely because its users were the most peaceful and well-behaved of vacationers. Soon, Prerow became known as the GDR’s nude camping capital.26

Some scholars have argued East Germans were so militant about protecting their access to nude recreation because they were seeking an escape from the regimentation of daily life. Others have mocked GDR citizens, saying they only went naked because they couldn’t afford swimsuits or that factories were unable to supply them under communism.27 State surveillance and consumer shortages were no doubt real enough in the GDR, but such shallow conclusions are the product of Cold War propaganda that ignore the opinions of the people who lived there.

According to internal survey data unearthed by McLellan, the reality was that many FKK enthusiasts saw themselves as socialists and framed their nudism as an expression of progressive values like equality and human fulfillment. Many believed they, rather than the paternalistic conservatives at the top of the SED, were the true communists. The class origins of those surveyed also debunked government claims that nude recreation was a bourgeois affair: 55% were from working-class backgrounds, while only 6% were born into educated white-collar families.28

Many of the younger and most eager nudists were actually products of the socialist system, beneficiaries of the upward mobility it provided for the children of workers and farmers. The party’s promise that Marxism-Leninism would cultivate free and forward-thinking people turned out to be true; it just happened that the people ran along the path toward liberation faster than the party itself.

In 1963, Neues Leben (New Life), the magazine of the Free German Youth (Freie Deutsche Jugend, FDJ), the SED-affiliated youth organization, broke new ground when it published a photograph of a nude communist young woman, face turned confidently toward the future.

A short time later, Junge Welt, the FDJ’s daily newspaper, published an article critiquing the lack of humanity in a Soviet art exhibit in Dresden: “During past centuries, the naked human form was depicted in great style by famous painters. What has happened to our socialist realism these days? Why do we shy away from nude men and women symbolizing the healthy strength of the working class? Why all this fuss about clothes or no clothes? It's about time that a new storm blew away those taboos which do not match with our progressive ideas for tomorrow!”29

It was abundantly clear, then, that the youth were in the vanguard of the nude revolution. The GDR’s comprehensive sex education program, implemented in the ’50s, was bearing fruit, producing a confident and body-positive generation. They’d learned that exposure to the naked body at a young age was a prerequisite for healthy adult sexual identities and that it inculcated respect for women and gender equality.30 The bottom-up push for a socialist nudism advanced rapidly as the debate over nudity came to occupy a prominent place in the conversations of public life.

It also received a bit of help from the top. In 1971, the Stalin-era SED party chief who’d led the GDR since its founding, Walter Ulbricht, was nudged aside in favor of 58-year-old Erich Honecker. While the new leader was by no means a democrat, his government was determined to craft a more modern and appealing socialist society, to make the GDR a place where people would want to live.

A cultural thaw soon set in, along with an easing of ideological rigidity and more concessions to citizen individualism. The government remained resolutely anti-capitalist, but it pursued a form of “consumer socialism” aimed at giving GDR citizens a greater stake in the system. This was matched by the GDR’s effort to gain more recognition and respect on the international stage.

Socialism strips down

The GDR of the ’70s was a young and forward-looking country, with fascism and the war now comfortably in the rear-view mirror. The economy advanced rapidly, putting the GDR at the head of the pack of socialist bloc countries. The workweek was shortened, wages were raised, housing improved in both quantity and quality, and laws forbidding homosexuality were overturned (though gay men and lesbians still lacked official recognition or rights).

Women enjoyed greater social equality as they became more financially independent via their own employment, and they could easily access contraception, abortion, and divorce. According to McLellan, “Freed from economic and ideological repression, women were able to build relationships with men based on mutual trust and respect” in these years.31

All these measures and others affected sexual behavior generally as well as attitudes concerning freedom of the body. Unlike in the capitalist countries, however, the sexual revolution in the GDR did not spawn a commercialization of sex; pornography was absent, and prostitution was unheard of. Instead, love became “more socially unburdened,” conditions for intimacy were “encouraged and optimized,” and a “sexuality without taboos” emerged.32

As one woman put it, “Not everything was good in East Germany, but in principle you could live out your sexuality freely.”33 It was in this context that nudism became a truly mass phenomenon in the GDR.

As the borders opened to international tourists, naturists from the west no longer had to speculate about what was happening behind the so-called Iron Curtain; they could go and see the situation for themselves.

One British naturist who spent time at the Dimitrov Recreation Center on the Baltic coast in 1971 wrote in the magazine Sun and Health:

“What’s so strange about Communist Germany? The odd thing about the beach was that it was public. We are not used to this kind of thing in England. Here, naturist clubs are hidden away, and their members, though exposing their bodies to one another, go to great lengths to conceal them from the general public. Members of the general public, for their part, often go to great lengths to spy on naturists. But in the GDR, no one on the naturist beach seemed to care whether the general public could see them or not. And for their part, members of the general public walking along the footpath beyond the bushes gave no more than a casual glance whenever they came to a gap that brought the naturist beach into full view. I suddenly realized that this was as it should be.”34

A visitor from the United States told readers of the Bare in Mind newsletter:

“For a change of pace, and for curiosity, you might want to venture into a Communist country while vacationing in Europe…. Whereas in the USA you find mostly single men, couples, a few single women, and very few families [at nude beaches], here in East Germany a more ideal situation exists. It is primarily families you find, then couples, and only relatively few singles. The East German naturist composition is thus…a section of the average population curve.”35

Another British tourist urged everybody to “try East German naturism at least once, for it is not the same as elsewhere.” Though there were no separate naturist organizations in the GDR, he observed the government “to be mindful of the increasing demand for naturist sites,” as demonstrated by the constant enlargement of naturist beaches and FKK lake zones at the expense of textile sections. But even if nudists strayed from their designated areas, there was little to worry about, for “to be found naked on unofficial grounds, beaches, or lakes is to risk nothing at all. It is tolerated.”36

Michael Behr, an East German who wrote to Bare in Mind, reiterated the same point: “At the beaches, there reigns a mixed culture…. People sunbathe and bathe in a completely free clothing style…. Everyone respects the free will of the neighbor who lies ten meters away.”37

In contrast to its reputation as a police state, when it came to body freedom, the GDR was actually more liberal than the capitalist countries. Nude recreation was accessible for everyone; there was no need to pay membership fees, join an association, or worry about discrimination on grounds of race, ethnicity, or marital status.

Western nudists often criticized the GDR for its lack of separate naturist organizations or private for-profit camps, citing this as proof of communist repression. But nudism actually flourished far more in East Germany precisely because it was public, because it was nationalized, and because it was socialist.

The state evolved from its previous grudging tolerance of FKK to the position of enthusiastic sponsor. Body positivity, greater connections to nature, the overcoming of ageism, the de-eroticization of the body, and enhanced gender equality—all were promoted by the SED government as benefits of nude culture.

It began to promote nudism as the socialist antidote to commercialized sexuality. East German naturists took to calling one another “comrade” and said they felt at home in the “collective community” of the nude beach or camp.38 By the early ’70s, a survey showed that 62% of young workers and 75% of students said they approved of nude swimming.39

Some commentators would later speculate that the reason the state gave FKK its stamp of approval so eagerly was that SED General Secretary Honecker was himself a “great supporter of nudism and liked to bathe naked.”40 Regardless of the party leader’s own proclivities, the truth is that the original pressure for change had come from below, and the result was that nudism became the norm in GDR society.

Daytime news programs sent naked reporters to the nude beach to answer the public’s questions about what it’s like to go for the first time. Feature articles on FKK recreation appeared regularly in prominent state-owned newspapers and magazines. Films and television series depicted nude recreation just as it would any other pastime, with no special attention, warnings, disclaimers, or advisories attached.

In 1976, when the Palace of the Republic, the new parliament building, opened in Berlin, it featured an exhibit titled, “Are Communists Allowed to Dream?”—based on a quote from Lenin. Its centerpiece was a painting of naked bathers called simply “Menschen am Strand” (“People on the Beach”).41

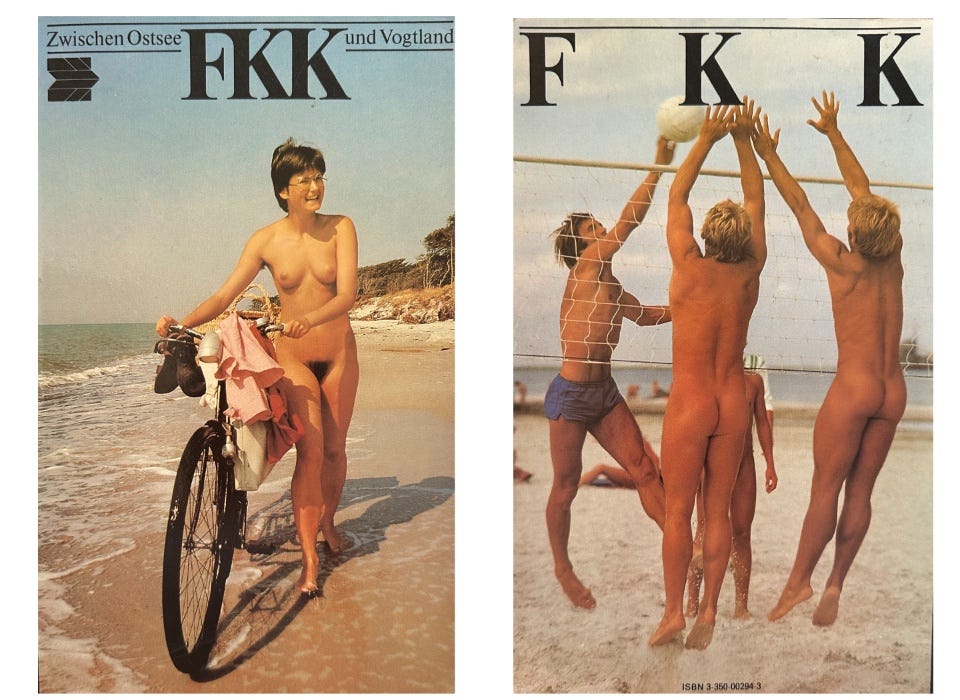

Nudism also became a major part of the government’s tourism campaigns, both domestic and international. Nudist camp facilities were regularly enlarged and modernized to meet the growing demands of an educated and increasingly well-off workforce seeking to rest and recuperate out in nature. Efforts were made to capture a share of the foreign naturist market, as well. In practice, the separation of FKK and textile beaches came to an end; naked and clothed bathers swam side-by-side. Public nudity was even deemed acceptable in designated areas of urban parks.

In 1982, the first East German nudist guidebook, Baden Ohne (Bathing Without), hit store shelves.42 It catalogued all the country’s nude beaches and inland nude swimming spots, or almost all of them—the unofficial gay nude beach, Müggelsee in Berlin, didn’t make the list. Put out by the state-owned VEB Tourist publishing house, the book saw print runs in the hundreds of thousands over the next several years. A review in the U.S. magazine Clothed With the Sun noted it was “attractively illustrated and useful.”43

Along with other socialist countries like Yugoslavia, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia, the GDR was setting the pace internationally for naturism, beginning to compete even with long-term hubs like France. The future of nude culture in the German Democratic Republic appeared bright.

This golden age of body freedom could not exist in isolation from the events and developments that were swirling around it, though. As the 1980s drew to a close, so too did East German socialism. The economic and political crisis that engulfed the Soviet Union during the Mikhail Gorbachev years spread to its allied states in Eastern Europe.

By late 1989—just two years after nudists strode through Berlin’s streets and waterways during the grand 750th anniversary parade—the Wall had crumbled, and the GDR’s days were numbered. On October 3, 1990, the country ceased to exist, as West Germany swallowed it up whole and capitalism was restored.

Capitalist cover-up

The end of socialism did not mean the end of nudism, of course. It was still Germany, after all, the original home of FKK. But nude culture had looked very different on the two sides of the inner-German border, and the merging of the Germanies exposed tensions which persist decades after the GDR’s disappearance.

While it counted more practitioners than many other nations, naturism in West Germany had remained a minority affair and it resembled places like Britain, France, or the U.S. Nude recreation was something that, with few exceptions, was mostly only enjoyed at private campgrounds or within very defined boundaries on (usually isolated) beaches—a sharp contrast to the open, public, and majoritarian nature of East German nudism.

A 1992 Washington Post headline summed up the difference in attitudes: “Eastern Nudes vs. Western Prudes.” Speaking to the Post’s reporter, former GDR citizen Annette Unger railed at the “Wessis”—West Germans—invading her Baltic coast town of Warnemunde. "I am not ashamed of my body; I have a good body, and I like to show it,” she said. “They are hypocritical, bringing us all their pornography and then telling me I cannot bathe naturally.”

She complained of the proliferation of “Nudity Prohibited” signs and of being badgered to put on a swimsuit at the beach. Another woman told the Post that in unified Germany, the human body and sexuality were being turned into commodities to be bought and sold. “If nudity was seen as natural,” the way it had been in the GDR, she declared, “they could not sell sex the way they want to.”44

West German laws related to nudity—restricting it to officially-designated times and places—were imposed on East Germans, along with capitalism, the market economy, and privatization of public property. The free beaches where the clothed and the naked had mingled without incident were once again segregated. The free or subsidized FKK holidays of the past were gone, and the union- and state-run hotels and campsites were now privatized and financially out of reach for many.

Access to several nude recreation facilities and grounds suddenly came with a price tag, as their owners—private individuals or dues-based organizations—charged hefty fees. Pornography became a staple on the magazine racks and video shelves of stores. Body shame and sexist attitudes toward women’s bodies, long disavowed in the GDR even if not totally eradicated, returned with a vengeance.

For many East Germans, it all amounted, quite literally, to a capitalist cover-up. The condescending attitudes of some West Germans only rubbed salt in the wound for those who wondered what they’d given up in exchange for bourgeois democracy. “Now they have the right to have their clothes on,” one wealthy West German remarked to a journalist. “They were naked before because they did not have bathing suits.”

Another, a man who’d paid top-dollar for a room in the formerly publicly-owned Neptun Hotel in Rostok, turned to insults. “The Ossies [Easterners] look better dressed,” he said. “Some don’t have figures to show, and it’s very unaesthetic. For some of those old grandmothers, they should have special [hidden] sections” on the beach.45

The attitude of West German chauvinism that was displayed in the early days of reunification continues in the present. Victor Grossman, a longtime GDR resident who still lives in united Germany today, says that historians are “occupied with denigrating everything about the GDR” and join in the pastime of oversimplifying nudism in the East as nothing but a “protest against strict authoritarian rule,” a “chance to get a small taste of freedom.”

When it comes to the GDR and socialism in Eastern Europe, they only conjure images of the Berlin Wall, secret police, or Soviet puppet governments. They dismiss any notion that the socialist societies that grew up in the east actually possessed some redeeming qualities in the eyes of many of their citizens.

For Grossman, who enjoyed FKK beaches with his family during the GDR years, nudity was simply about avoiding wet bathing clothes, getting some sun, and enjoying the friendly and comradely spirit that prevailed. Before the Wessis came, he said, no one saw any reason for shame.46

Mario Lars, author and illustrator of a 2020 book of FKK cartoons who grew up in the GDR, wrote about his memories of the past and how things have changed:

“I walked along the pristine Baltic Sea beach of my youth, and there were naked people lying everywhere in the sand, as God had created them, as they say…. Whether young or old, wrinkled or toned, fat or thin, they were all equally naked on the beach…. When the Wall fell and the GDR disappeared into the history books, when voyeurs fell in love with our beaches, the small, once naked country was flooded with swimsuits and trunks…. The East German Baltic Sea beach lost its virginity, and now there are people lying on the beach dressed, as if God had not created them, as they say. They are still fat or thin, wrinkled or toned. They just don’t dare show it anymore. The naked people were locked away, often in small, remote reserves. And there they have remained in their niches to this day.”47

Neither the GDR government nor the SED ever attempted to craft a full theoretical underpinning for socialist nudism in Marxist terms, but historian Mark Storey developed a Marxist argument for naturism, seeing it as a means of combatting the alienation, or estrangement, humans feel from one another under capitalism.

Though originally developed by Karl Marx and Frederick Engels as a way of analyzing how the division of labor, exploitation, and the commodity economy estrange people from the products they create and the ideas they formulate, later scholars have expanded the theory of alienation to other areas of life.48

According to Storey, prohibitions on nudity and the forced adoption of clothing “alienates us from each other” via the “social status that clothing confers.” He wrote in 1997:

“All humans are of equal inherent value, but clothing, probably more than anything else, conveys a false sense of hierarchy. When you are naked talking to a naked person, you are forced to relate to that person on more even terms. There are other false or artificial barriers someone may put up, but social nudity removes most economic and social restrictions that are not essential to a person’s character.”49

German sexologist and researcher Kurt Starke, discussing the GDR in the 2006 film Do Communists Have Better Sex?, made a similar observation concerning alienation and nudity:

“Once a nudist, always a nudist. Everyone was equal, it wasn’t organized, you didn’t have to join a club. People lived that way and felt free. It reflected a different attitude toward the body. If I live in a society where I can’t sell my body, I have another kind of freedom. I’m not distanced from my body, which happens if I can sell it.”50

Socialist nudism in the GDR may never have had the official backing of the ideological guardians of Marxist-Leninist philosophy, but such a stamp of approval was unnecessary. The “people’s nudism” which developed in this small country during its 40 years of existence was the product of grassroots longing for human connection; it was a revolution from below driven by collectives of people searching for comradeship, equality, and authenticity.

The people of the GDR were reared on the promises of a party and state that pledged a more egalitarian and prosperous future. Many of them concluded that taking off their clothes was one way to speed up their journey along that path to a socialist tomorrow.

They would have no doubt found common cause with Mark Storey’s paraphrasing of the closing lines of The Communist Manifesto:

“Marx wanted to change the world, and so should we. Let the prudish classes tremble at a naturist revolution. Naturists have nothing to lose but their clothes. They have an Eden to gain. Naturists of all countries, unite!”51 🪐

Appreciation to the Nudist Research Library Consortium for access to their collections.

Cited by Josie McLellan, Love in the Time of Communism: Intimacy and Sexuality in the GDR. Cambridge University Press, 2011, p. 144.

Exhibit: “Politics Without Swimming Trunks.” DDR Museum, Berlin. Viewed by the author, August 2022.

Josie McLellan, “State Socialist Bodies: East German Nudism from Ban to Boom,” The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 79, No. 1, March 2007. (pp. 48-79).

Michael Hau, The Cult of Health and Beauty in Germany: A Social History, 1890-1930. University of Chicago Press, 2003.

John Alexander Williams, Turning to Nature in Germany: Hiking, Nudism, and Conservation: 1900-1940. Stanford University Press, 2007.

See Jan Gay’s account of her visit to Koch’s school in the early 1930s: Jan Gay, On Going Naked. Garden City Publishing, 1932, Ch. 3.

See the “Über uns” (“About Us”) section on the website of the Familien Sport-Verein Adolf Koch e.V. (Adolf Koch Family Sports Club), available here: https://www.adolf-koch.de/ueber-uns/

Williams, p. 17.

Quoted by Michael Andritzky and Thomas Rautenberg, eds., “Wir sind nackt und nennen uns Du”: Von Lichtfreunden und Sonnenkämpfern—eine Geschichte der Freikörperkultur. Anabas, 1989, p. 57.

Quoted by Williams, p. 38.

Williams, p. 24-5.

Quoted by Williams, p. 39.

See: Curtis Atkins, “Down With Shame! Soviet nudism, Lenin the nudist, and the naked communists of the 1920,” Planet Nude. Feb. 28, 2023. https://www.planetnude.co/p/down-with-shame

Maurice Parmelee, Nudism in Modern Life: The New Gymnosophy. Alfred A. Knopf, 1931. pp. 36, 13.

Several of the socialist nudists of the 1920s had been paranoid about the efforts of right-wing nationalists and the Catholic Church to connect their movement to homosexuality and took great efforts to restrict participation by gay men. Though Adolf Koch and other leaders held relatively progressive views about the inborn nature of homosexuality and the fruitlessness of any effort to change a person’s sexuality, others, like Hans Graaz, worried that gay men were too subject to blackmail, and thus, “through no fault of their own” posed a danger to the nudist community. So, just like the left-wing movement in the U.S. did during the Red Scare in the 1940s and ’50s, Germany’s socialist nudists sought to exclude homosexuals in the name of security. Such efforts, of course, did nothing to save their organizations from the Nazis.

Matthew Jeffries, “’For a Genuine and Noble Nakedness’? German Naturism in the Third Reich,” German History, Vol. 24, No. 1, 2006. (pp. 62-84).

Chad Ross, Naked Germany: Health, Race, and Nation. Bloomsbury Academic, 2005.

McLellan, Love in the Time of Communism, p. 147.

Ibid., pp. 150-51.

Cited by McLellan, p. 153.

“Nudism Banned in Soviet Germany,” Sunny Trails, Vol. 6, No. 4, April 1957, p. 11.

Reuters, “East Germans Ban Nudism,” New York Times, June 10, 1956, p. 81.

“INF in touch with Soviet Zone Government Office,” International Nudistour Guide, Vol. 1, No. 4, 1963, pp. 38-9.

Rolf Kellenhusen, “Can Communism and Nudism Peacefully Coexist?” Sundial, Vol. 3, No. 2, September 1964.

Victor Grossman, A Socialist Defector: From Harvard to Karl-Marx-Allee. Monthly Review Press, 2019, pp. 76-77.

McLellan, Love in the Time of Communism, pp. 155-56.

Humorist Will Rogers had said the same of the Soviet Union in the 1930s after witnessing mass nude swimming there. See: Will Rogers, There’s Not a Bathing Suit in Russia. Oklahoma State University Press, 1973 (reprint), pp. 75-80.

McLellan, Love in the Time of Communism, pp. 155-56.

Kellenhusen.

Kristen Ghodsee, Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism—And Other Arguments for Economic Independence. Bold Type Books, 2018.

McLellan, Love in the Time of Communism, p. 2.

Ibid.

Quoted by McLellan, Love in the Time of Communism, p. 1.

Ernest Trory, “British Naturists in East Germany,” Sun and Health #65, 1971, pp. 4-5.

Leif Heilberg, “FKK Naturism in East Germany,” Bare in Mind, January 1986, pp. 13-14.

Hans Schmidt, “Naturism in East Germany,” British Naturism #92, Summer 1987, p. 16.

Michael Behr, “As Walls Tumble: Nudism in East Germany,” Bare in Mind, Vol. 18, No. 7, Summer 1990, p. 1 and 14.

Survey data cited by McLellan, Love in the Time of Communism, p. 161.

Ibid., p. 165.

See: Lothar Herzog, Honecker Privat. Neue Das Berlin GmbH, 2012.

Also: “Servant ousts Honecker as a nudism fan,” FOCUS, Sept. 10, 2015. https://www.focus.de/panorama/welt/diener-outet-erich-honecker-als-fkk-fan-private-seiten-des-ddr-staatschefs_id_2106314.html

Bärbel Mann and Jörg Schütrumpf, “Galerie im Palast der Republik. Auftraggeber: Ministerium für Kultur,” in Monika Flacke (ed.), Auftrag: Kunst 1949-1990. Bildende Künstler in der DDR zwischen Ästhetik und Politik. Deutsches Historisches Museum, 1995, pp. 245-60.

Baden Ohne. VEB Tourist Verlag, 1982.

“East Germany,” Clothed With the Sun #044, Winter 1984-85, p. 46.

Kara Swisher, “Eastern Nudes vs. Western Prudes,” The Washington Post, September 5, 1992.

Ibid.

Grossman, p. 78.

Mario Lars, FKK: Die Nackte Wahrheit—Cartoons mit ohne Badehose. Bild Und Heimat, 2020, pp. 5-6.

Marx and Engels argued that humans were essentially productive beings who relate to one another and to nature through our act of creating—material things like food, houses, art, or steel, as well as immaterial objects like ideas and scientific theories. By denying us of the ability to determine how we use our productive capabilities and stripping us of the things we create by privatizing them, capitalism alienates us from our own nature and from one another. Communism, or the socialization of property and commodities, is the negation of such alienation. See: Karl Marx, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844; and Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, The German Ideology.

Mark Storey, “Social Nudity and Freedom from Alienation,” Naturist Life International, No. 20, Autumn 1997, p. 29.

Kurt Starke, commentary in the film, Do Communists Have Better Sex? (2006). Available online.

Storey, p. 29.

Fabulous article on nudity in East Germany. It would be nice if we could take a lesson on how to really enjoy freedom and appreciate our bodies from the attitudes of these founders of an early nudist movement. Thanks for bringing this to our attention.

I love this excellent article!! It seems all very valid and consistent with my limited experience of FKK in the DDR. I would love to see a similar article covering nudism and naturism in the Federal Republic of Germany during the same years, with some exploration of why nudism is still more widely accepted in Germany than in other cultures currently.