Edward Carpenter and the intellectual roots of naturism

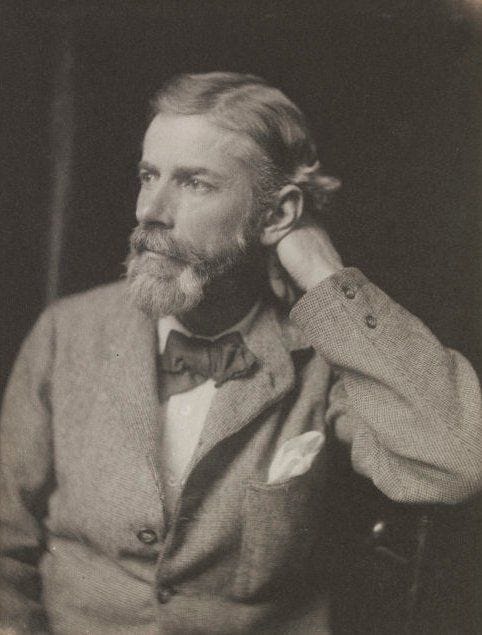

The queer Victorian rebel who brought Walt Whitman’s spirit and social nudity to the UK

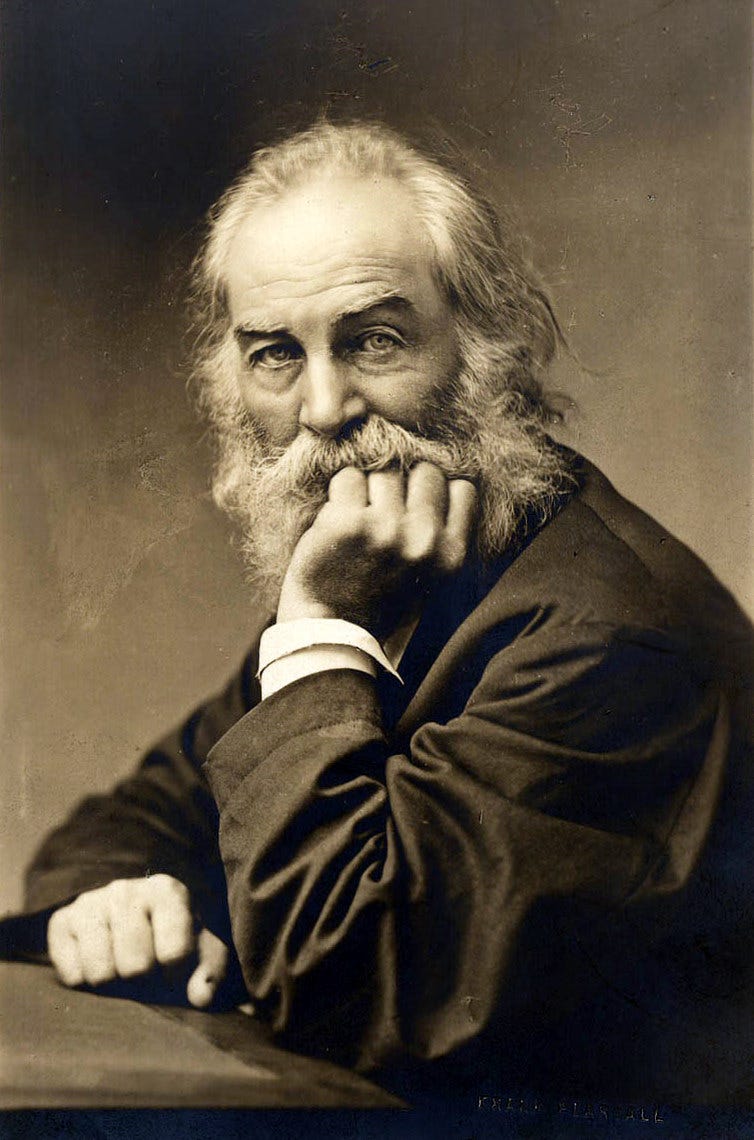

Edward Carpenter did not invent social nudism. But long before it had a movement, a magazine, or a federation, he gave it language. Drawing deeply from Walt Whitman’s poetry and expanding those ideas into philosophy, politics, and lived practice, Carpenter connected the naked body to freedom, health, and spiritual renewal. His work forms a bridge between nineteenth-century radical thought and the organized naturism that would follow.

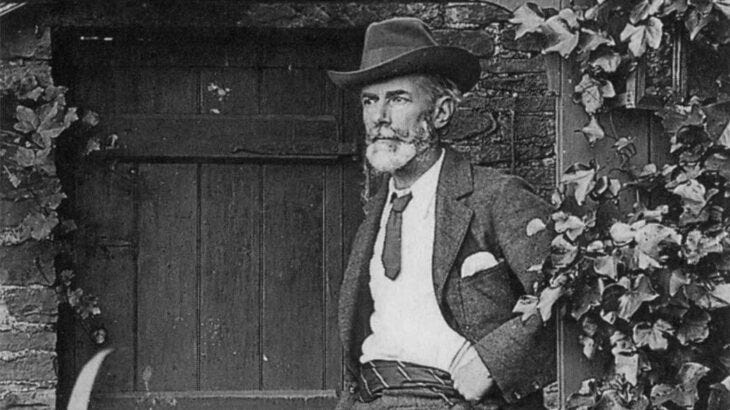

Song of Myself was written when Walt Whitman was about 37, and first published in 1855. Edward Carpenter (1844–1929) of the United Kingdom later commented that it was a composite of so much of what Whitman would come to write over his lifetime and had the elements that offered the title of his meta-work Leaves of Grass. Carpenter felt that Whitman was a true prophet, and this particular poem is steeped with spiritual aspects and a connection to all of humanity and nature; we are all one in life, on Earth, and in the universe. It is a treatise of the diversity of America, the breadth of nature, and the oneness of it all.

Edward Carpenter went on to promote social nudity and gay rights in the UK. Carpenter would later become one of the earliest public advocates for homosexual rights in Britain and lived openly with his lifelong partner, George Merrill.

Sheila Rowbotham provides many details in her 2009 biography Edward Carpenter: A Life of Liberty and Love. He is cited as being Britain’s first nudist. As a young man Carpenter read Walt Whitman. He traveled to the USA in 1877 to meet with Whitman. They corresponded about getting back in touch with nature, breaking down class structures, socialism, and returning to pride in workmanship during the early industrial revolution. Carpenter wrote Toward Democracy in 1881, which some say reads like Walt Whitman’s poetry.

Whitman in the open air

Days With Walt Whitman — With Some Notes on His Life and Work was written by Carpenter and published in 1906. It summarized his visits with Whitman in 1877 and 1884. About their meeting in 1877 Carpenter writes:

It was his delight, and doubles one of the chief attractions of his favorite resort, to go down and spend a large part of the day by the “creek” which I have spoken of – and which figures so largely in “Specimen Days.” At a point not a quarter mile distance from the house it widened into a kind of little lake surrounded by trees, the haunt of innumerable birds; and here Whitman would sit for hours in an old chair; silent, enjoying the scene, becoming a part of it, almost, himself; or would undress and bathe in the still, deep pool. At this time he was nearly sixty years old, and for some eight years on and off had been stricken with paralysis. As is well known, he attributed his partial recovery very largely to the beneficence of this creek, with its water-baths and sun-baths and open-air influences generally.

In the same book Carpenter provides Whitman as Prophet. He waxes on that Whitman’s writings compare to the classic texts of the gospels of Jesus, the Eastern Upanishads and Bhagavad Gita, as well as Sayings of Lao-tzu, offering comparisons of thoughts and philosophies.

Carpenter looks at the inward references from Whitman and discovers that “underneath clothing, costume, ranks, trades, and occupations, the bodily form, its needs and physiology” and greater than the lessons from “the open air”;

In such simple elementary things as these — in the universal human soul, rediscovering itself in all forms, in the healthy and beautiful human body, in sex and fraternity, in the life with the earth and the open air, Whitman sees the root out of which future humanity will spring (as it has sprung in the past): out of which a society of proud, strong, free individuals who shall be brethren and lovers, may easily and naturally arise…

1881 was the same year that Carpenter read the Bhagavad Gita. He traveled to India and took up the habit of wearing sandals, which he wore the rest of his life. Carpenter associated with John Ruskin and William Morris of the British Arts and Crafts movement working toward simplicity in hand-crafted products. He returned to the USA in 1886 and again visited Whitman. Meanwhile, Whitman likewise inspired the likes of Elbert Hubbard and the Arts and Crafts movement in the USA. Carpenter, while striving for simplicity, kept a portrait of Whitman in his Millthorpe home in England.

In 1883 and revised in 1902, Carpenter wrote Towards Democracy. In it is a poem “In a Scotch-Fir Wood” where he reflects on a person going among the pine trees and listening to their advice:

O man, when wilt thou come fit comrade of such trees,

Fair mate and crown of such a scene?

Poor pigmy, botched in clothes, feet coffined in boots,

Braced, stitched, and starched,

Too feeble, alas! too mean, undignified, to be endured –

Go hence, and in the centuries come again!

Carpenter opens his 1889 book Civilisation: Its Cause and Cure with a Whitman quote: “The friendly and flowing savage, who is he? Is he waiting for civilization, or is he past it, and mastering it?” This suggests that both Whitman and Carpenter appreciated that the Eastern-based American Indians may have within their cultural foundations the philosophies that had moved around the globe from Asia. The oneness of nature and simplicity in living. Being nude in nature.

Carpenter’s 1889 book is remarkable in that he wrote about how civilization came about from hammering through and forging alliances of small groups of nomadic people. Great ideas were codified, and social structures established leading to cities and nations, as well as beliefs and religions. He then proposed, as he gazed into the future, that civilization will become global with worldwide standards and means of communicating. Some new concepts will be required that are very foreign to the thinking of the late 19th century. He mused that future generations will see the need to discard the structures that were developed to build systems. He concluded that a greater understanding will develop of the need to go back to nature, work collectively, and discard the things that are no longer needed, “and developing among others into the gospel of salvation by sandals and sunbaths!” Going back to simplicity by removing superfluous clothing he saw as an aspect of the cure to civilization.

Undoing the wrappings

In the book Carpenter wrote of how the vexation of civilization may be addressed by moving back to nature.

For no outward government can be anything but a make-shift – a temporary hard chrysalis-sheath to hold the grub together while the new life is forming inside – a device of the civilization-period….

Man has to undo the wrapping and the mummydom of centuries, by which he has shut himself from the light of the sun and lain in seeming death, preparing for his glorious resurrection – for all the world like the funny old chrysalis that he is. He has to emerge from houses and all his other hiding places wherein so long ago ashamed (as at the voice of God in the garden) he concealed himself – and Nature must once more become his home, as it is the home of the animals and angels.

As it is written in the old magical formula: “Man clothes himself to descend, unclothes himself to ascend.” Over his spiritual or wind-like body he puts on a material or earthy body; over his earth-body he puts on the skins of animals and other garments; then he hides his body in a house behind curtains and stone walls – which become to it as secondary skins and prolongations of itself. So that between the man and his true life there grows a dense and impenetrable hedge; and what with the cares and anxieties connected with his earth-body and all its skins, he soon loses the knowledge that he is a Man at all, his true self slumbers in a deep and agelong swoon.

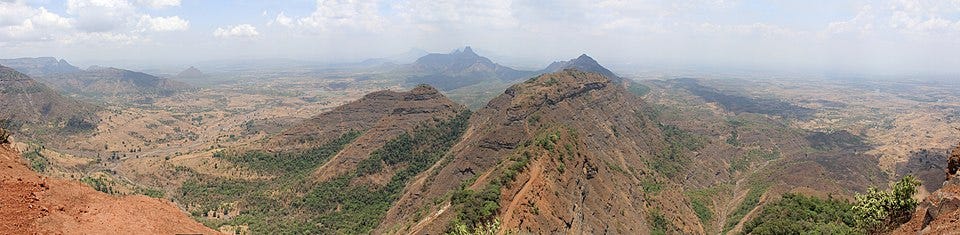

Carpenter produced From Adam’s Peak to Elephanta in 1892 summarizing his trip to India in 1890. Not only did he comment on his own sunbathing but described the value of living without clothes.

I fancy we make a great mistake in these hot lands in not exposing our skins more to the sun and air, and so strengthening and hardening them. In the great heat and when constantly covered with garments, the skin perspires terribly, and becomes sodden and enervate, and more sensitive that it ought to be – hence great danger of chills. I have taken several sun-baths in the woods here at different times, and found advantage from doing so.

[Since writing the above, I have discovered the existence of a little society in India – of English folk – who encourage nudity, and the abandonment as far as possible of clothes, on three distinct grounds – physical, moral, and aesthetic – of Health, Decency, and Beauty. I wish the society every success. Passing over the moral and aesthetic considerations – which are both of course of the utmost importance in this connection – there is still the consideration of physical health and enjoyment, which must appeal to everybody. In a place like India, where the mass of the people go with very little covering, the spectacle of their ease and enjoyment must double the discomforts of the unfortunate European who thinks it necessary to be dressed up to the eyes on every occasion when he appears in public. It is indeed surprising that men can endure, as they do, to wear cloth coats and waistcoats and starched collars and cuffs and all the paraphernalia of propriety, in a severity of heat which really makes only the very lightest covering tolerable; nor can one be surprised at the exhaustion of the system which ensues, from the cause already mentioned. In fact, the direct stimulation and strengthening of the skin by sun and air, though most important in our home climate, may be even more indispensable in a place like India, where relaxing influences are so terribly strong. Certainly, when one considers this cause of English enervation in India, and the other due to the greatly mistaken diet of our people there, the fearful quantities of flesh consumed, and of strong liquors – both things which are injurious enough at home, but which are ruinous in a hot country – the wonder is not that English fail to breed and colonise in India, but that they even last out their few years of individual service there.]

Carpenter may have taken Whitman’s ideas and catalyzed the Indian group practicing social nakedness. In India in 1891, the British sparked an idea. It appears that correspondence between Judge Charles Edward Gordon Crawford and provocateur Edward Carpenter led to the formation of the Fellowship for the Naked Trust (FNT).

A group of three, Crawford along with Andrew and Kellogg Calderwood, met near Thane, on Salsette Island northeast of Mumbai to enjoy days without clothes. Crawford in other correspondence commented that his late wife stated that she would be accepting of life without clothing. There was a female who was interested in the activities of the FNT, but she apparently never joined the group.

Crawford wrote to Carpenter:

Andrew Calderwood and I were up at Matheran having two day’s holiday to spend naked from breakfast to evening. But that was only by shutting ourselves up tight in our room. Being indoors at our FNT meetings does not of course employ quite the same shutting up as it does in England. The room where we have “met” in this house is upstairs, lofty and spacious, and full of windows. In June Andrew Calderwood and I had a grand day. We went away to a bungalow in the Tulsi Lake without servants and spent from dinner time Saturday till five pm Sunday in nature’s garb. Servants are the great difficulty, because they are everywhere. At Tulsi, where we were quite isolate, we were able to stroll about in the veranda and round the house. I am writing this in “uniform” and we have retired to a secluded room for the purpose of spending a few hours so.

In 1892 Crawford remarried and by 1893 the FNT had ended. The very small, British-based, short-lived experiment in social nakedness in Asia had been documented and then ended. The Fellowship for the Naked Trust is cited as being the first organized nudist group in the world, and it was located in India, not far from the home of the Gymnosophists, although its purposes were different from seeking enlightenment through the discarding of material things. Carpenter was even made an “honorary member” of The Fellowship of the Naked Trust according to Sheila Rowbotham and Jeffrey Weeks in their Socialism and the New Life.

Carpenter wrote Angel’s Wings in 1898 and eloquently expressed his admiration for Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. He compared Wagner’s music, Millet’s painting, and Whitman’s poetry. Also, in Angel’s Wings Carpenter expresses his sense of how the human form and art are intertwined in an entire chapter, “The Human Body in its Relation to Art.”

That the representation of the body in Art should touch us so nearly, and that the sense of Beauty should be so especially associated with the delineation of the human figure may now seem easy to understand. For every outline and feature of the latter wakes trains of emotion in us, and is radiant with meanings. To look at a perfect body, in which all the parts are harmonized and in healthful relation, is to have by suggestion all the emotions of which the soul is capable brought into touch with each other. Thus there awakes far back in the mind a sense of harmony or health of the Soul itself – the stirring within us of some divine and universal Being – to be capable of feeling which is indeed the most excellent prerogative of Man; a sense which we endeavor to express by the word Beauty, and the conveyance of which is the highest message of Art.

We shall not I think go very far wrong if we say that in the free sane acceptance of the human Body, in all its faculties, lies the Master-key to the Art of the future.

In 1892 and revised in 1904 Carpenter wrote “Health a Conquest,” that appeared within the 1921 fifth edition compilation of a number of his articles. He reflected on his 1890 experiences in India and wrote:

Certainly the exposure of the skin to the sun and air is one of the most important conditions of health; and I believe that what we call ‘catching cold’ is greatly due to our everlasting covering it, and so checking the action of its innumerable glands.

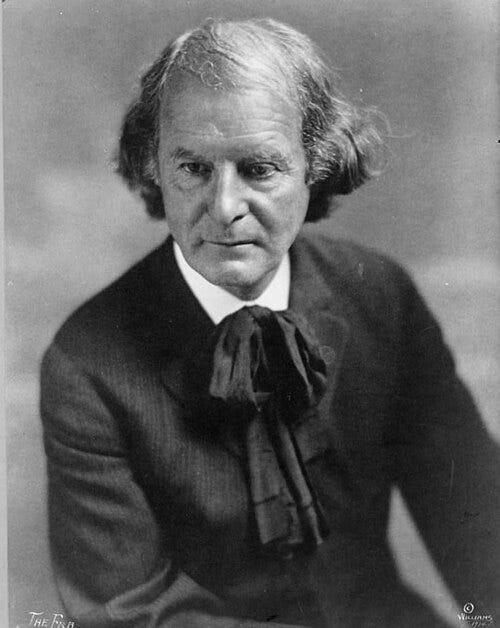

In 1903 Carpenter wrote Love’s Coming-Of-Age. He references the notorious, fictional, but always present and objectionable “Mrs. Grundy.” In it he describes the healthy attitudes that youth have toward the body, albeit the challenges they face.

Our public opinion, our literature, our customs, our laws, are saturated with the notion of the uncleanness of Sex, and are so making the conditions of its cleanness more and more difficult. Our children, as said, have to pick up their intelligence on the subject in the gutter. Little boys bathing on the outskirts of our towns are hunted down by idiotic policemen, apparently infuriated by the sight of the naked body, even of childhood. Lately in one of our northern towns, the boys and men bathing in a public pool set apart by corporation for the purpose, were – though forced to wear some kind of covering – kept till nine o’clock at night before they were allowed to go into the water – lest in the full daylight Mrs. Grundy should behold any portion of their bodies! and for women and girls, their disabilities in the matter are most serious.

Till this dirty and dismal sentiment with regard to the human body is removed there can be little hope of anything like a free and gracious public life. With the regeneration of our social ideas the whole conception of Sex as a thing covert and to be ashamed of, marketable and unclean, will have to be regenerated. That inestimable freedom and pride which is the basis of all true manhood and womanhood will have to enter into this most intimate relation to preserve it frank and pure – pure from the damnable commercialism which buys and sells human things, and from the religious hypocrisy which covers and conceals; and a healthy delight in and cultivation of the body and all its natural functions, and a determination to keep them pure and beautiful, open and sane and free, will have to become a recognized part of national life….

But however things may change with the further evolution of man, there is no doubt that first of all the sex-relation must be divested of the sentiment of uncleanness which surrounds it, and rehabilitated again with a sense almost of religious consecration; and this means, as I have said, a free people, proud in the mastery and the divinity of their own lives, and in the beauty and openness of their own bodies.

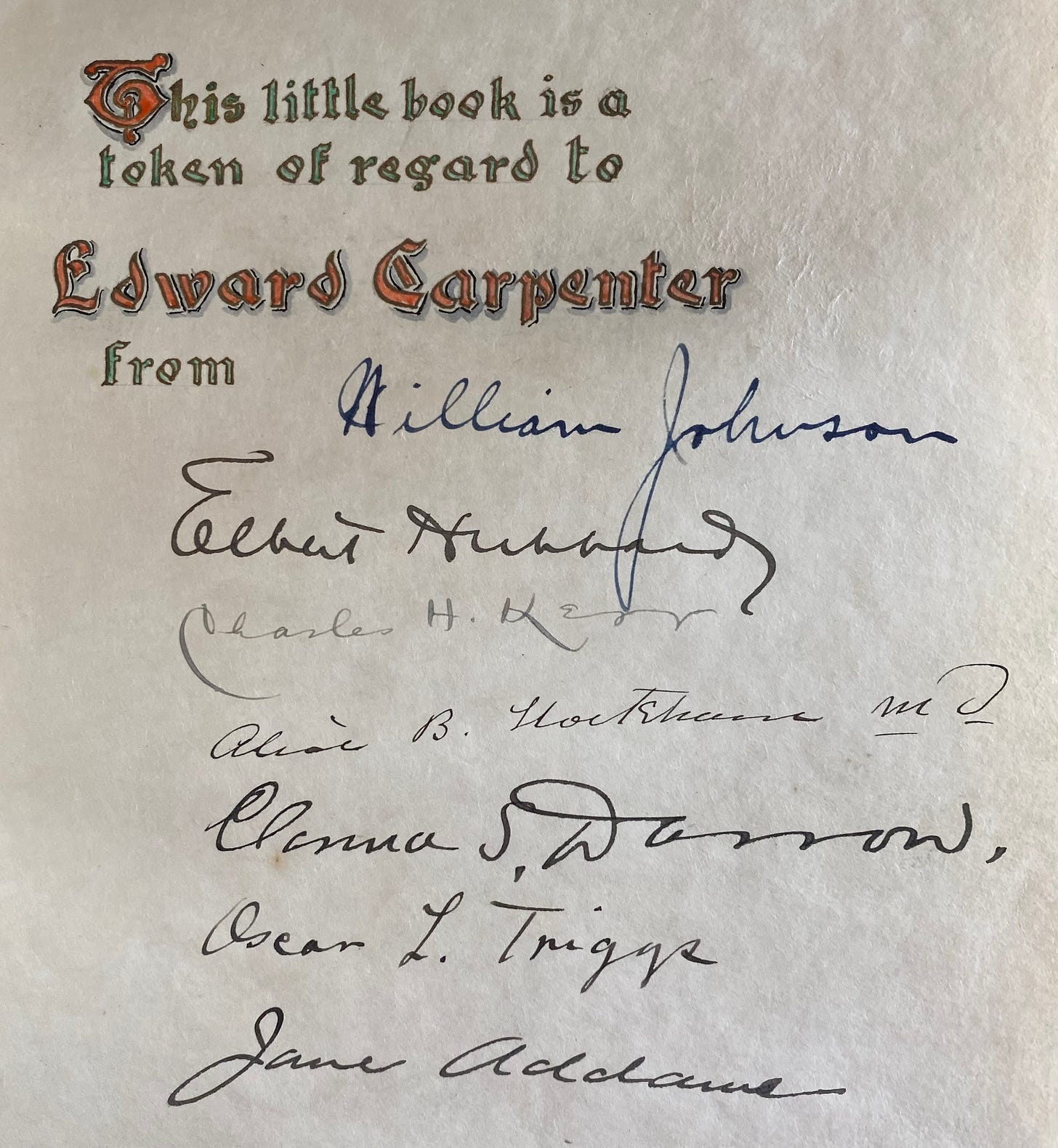

A book that is not a book

In 1904 Elbert Hubbard had 100 copies of Whitman’s Song of Myself printed and bound at Roycroft. This may have been for what would have been the 85th anniversary of Whitman’s birth or in anticipation of the 50th anniversary of the book’s first publication in 1855. Copy #37 was prepared for Carpenter’s 60th birthday. It was hand illuminated with “This little book is a token of regard to Edward Carpenter from.” It was then signed by seven significant individuals whose names read like a roll call of early twentieth-century reform.

William Johnson, likely the one from Coventry, NY, known as “Pussyfoot” for his prohibition work in Indian territories of Oklahoma, leader of the Anti-Saloon League, and active in the temperance movement, who traveled globally with the World League Against Alcoholism.

Elbert Hubbard, director of Roycroft and leader in the Arts and Crafts movement in the USA, who challenged the social norms of clothing of the time and in 1898 and 1908 published Carpenter, Morris, Salt, Shaw, and Wallace’s Hand and Brain: A Symposium of Essays on Socialism.

Charles H. Kerr, whose family moved from Georgia to Wisconsin via the Underground Railroad, a publisher who produced International Socialist Review along with radical, socialist, feminist, temperance, and labor histories, publishing Clarence Darrow, Isadora Duncan, Jack London, and Upton Sinclair, and sympathetic to the Industrial Workers of the World.

Alice B. Stockham, MD, who in 1892 became the fifth woman to earn a medical degree in the USA, an OBGYN who established her own publishing company to produce progressive literature, supported equal rights, dress reform, birth control, and sex education, promoted tantra sex, befriended Havelock Ellis, opposed tobacco and alcohol, and was defended by Clarence Darrow in 1905 for sending the 1903 edition of her book Karezza on marital couples sex and health education materials through the mail, a case that cost her dearly.

Clarence S. Darrow, attorney in the Scopes Monkey Trial and in Alice B. Stockham’s trial, and an early supporter of the American Civil Liberties Union.

Oscar L. Triggs, expert on Walt Whitman, who met William Morris of the Arts and Crafts movement in the UK in 1883 and twice visited Merton Abbey Mills, a site of Morris’s socialist activities, who may also have met Edward Carpenter while in the UK, and who later became a founding member of the Industrial Arts League in 1899 and founder of the first Morris Society, 1903–05, in Chicago.

(Laura) Jane Addams, founder of Hull House in Chicago, feminist, charter member of the NAACP, suffragette activist, founding member of the American Sociological Society in 1905, the first woman to receive an honorary Master of Arts degree from Yale University in 1910, co-founder of the ACLU in 1920, Nobel Peace Prize winner in 1931, later inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame and the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame.

On the closing page of the book is a statement printed in all uppercase letters in red ink:

SO HERE ENDETH THE “SONG OF MYSELF,” AS WRITTEN BY WALT WHITMAN. DONE INTO PRINT [THIS IS NO BOOK, WHO TOUCHES THIS TOUCHES A MAN.] BY THE ROYCROFTERS AT THEIR SHOP, WHICH IS IN EAST AURORA, ERIE COUNTY, NEW YORK, U. S. A. COMPLETED IN FEBRUARY, ANNO DOMINI, MCMIV

The square-bracketed line comes from Whitman’s “So Long!” first published in 1860. One line later he writes, “It is I you hold and who holds you,” followed by, “Dear friend whoever you are take this kiss, I give it especially to you, do not forget me.” Whitman’s voice remains startlingly present.

In the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass, the final poem included in the volume was “So Long!” Did Oscar Triggs, the Whitman scholar, suggest this square-bracketed notation? Did it enter the citation through Elbert Hubbard or even the Roycroft typesetter? Was the passion between Whitman and Carpenter known, and this note offered as quiet assurance? The 1924 and 1950 editions of Leaves of Grass include an introduction by John A. Kouwenhoven that ends with the same words found in the brackets. They were well known Whitman words and intentions.

Copy #37’s red ribbon page marker remains pressed in place at sections 28, 29, 30, and 31. The end of 28 and the beginning of 29 dwell on “touch,” and section 31 opens with “I believe a leaf of grass in no less than the journey-work of the stars.” Whitman’s life work became the compilation he titled Leaves of Grass. He wrote from his mind’s eye of the world he embodied.

It is fitting that the Roycrofters declared, “This is no book, who touches this touches a man.” To hold this item is to be with Walt Whitman and Edward Carpenter, along with Jane Addams, Clarence Darrow, Elbert Hubbard, William Johnson, Charles Kerr, Alice Stockham, Oscar Triggs, and the unnamed Roycrofters who produced it. This remarkable document now resides at the Western Nudist Research Library in Temescal Valley, California.

Editor’s note: The Roycroft edition mentioned above now resides at the Western Nudist Research Library thanks to the author, who acquired and donated the volume but characteristically did not mention that detail in the text. Carl Hild’s decades of collecting, research, and preservation have substantially shaped WNRL’s holdings, including rare international naturist publications and early documents that push back the accepted timeline of American social nudism. In recognition of this work, the library formally established the Carl Hild Collection in his honor last summer.

In a parallel gesture, in 1914, nearly 300 individuals signed The Address to Carpenter for his 70th birthday. The signatories included at least three future Nobel Prize recipients and an Academy Award winner for Best Screenplay, alongside a remarkable cross-section of reformers, artists, and intellectuals.

Jane Addams, who had also signed Carpenter’s 60th birthday greeting, was among them.

Photographer Alvin L. Coburn, who famously photographed Bernard Shaw posing nude as Rodin’s The Thinker, signed the address, as did Shaw himself.

Sanshiro Ishikawa, later associated with nudism in Japan, was another signer. According to Daniel William Schnick’s 1995 thesis at the University of British Columbia, Ishikawa returned to Japan in the 1920s, embraced anarchist positions after World War II, and participated in nude bathing at hot springs in defiance of prohibitions enacted in 1872. A 1970 article by Chushichi Suzuki described Ishikawa’s view of “nudity as the symbol of natural freedom.”

Gwen John, who modeled nude for Rodin, added her name. So did John Nicholson, whose poem about nude bathing appeared in the April 1894 issue of The Artist and Journal of Home Culture.

Poet Alfred Noyes signed as well. His story The Return of the Scare-Crow, published in the United States as The Sun Cure in 1929, centered on an attempt at sunbathing. Cecil Reddie, reportedly influenced by Walt Whitman and early German FKK culture, was included, as was painter Henry S. Tuke, known for his love of nude sea swimming and paintings of boys by the shore.

Several signers were closely aligned with Whitman’s circle and with broader movements for sexual equality and communion with nature, including Frank and Mildred Bain, Leon Bazalgette, John Burroughs, T. W. Rolleston, Horace Traubel, and J. W. Wallace.

Taken together, the nearly 300 names form a striking panorama: artists, Dames, humanitarians, Knights, Nobel laureates, politicians, prohibitionists, Quakers, royalty, suffragettes, socialists, Theosophists, Trotskyites, unionists, vegetarians, and writers. It reads like a roster of progressive thought at the turn of the twentieth century.

Carpenter responded with a thank you note on 1 September in which he wrote about coming to be conscious of The Victorian Age in 1860 and that it was “a strange period of human evolution.” He goes on to give some examples of the things that “marked the lowest ebb of modern civilized society”

…the starving of the human heart, the denial of the human body and its needs, the huddling concealment of the body in clothes, the “impure hush” on matters of sex, class-division contempt of manual labour, and the cruel barring of women from every natural and useful expression of their lives, were carried to an extremity of folly difficult for us now to realise….

If the world or any part of it should in consequence insist on being reformed, that is not my fault. And this perhaps after all is a good general rule: namely that people should endeavor (more than they do) to express or liberate their own real and deep-rooted needs and feelings. Then in doing so they will probably liberate and aid the expression of the lives of thousands of others; and so will have the pleasure of helping, without the unpleasant sense of laying anyone under an obligation.

In 1916, Carpenter wrote My Days and Dreams – Being Autobiographical Notes. In it he expressed himself and described his life and what was important to him. From his 1873 trip to Italy:

The Greek sculpture had a deep effect. The other things, pictures, architecture, etc., interested me much from an historical or aesthetic point of view; but this had something more, a germative influence on my mind, which adding itself to and corroborating the effect of Whitman’s poetry, left with me as it were a seed of new conceptions of life. The marvelous beauty and cleanliness of the human body as presented by the Greek mind, the way in which the noblest passions of the soul – the tender pitying love of Diana for Endymion, the haughty inspiration of Juno, the heroic endurance of the fallen warrior, the childlike gladness of the faun – were united and blended with the corporeal form – or rather scarcely conceived of as separated from it; the emotional atmosphere which went with this, the Greek ideal of the free and gracious life of man at one with nature and the cosmos – so remote from the current ideals of commercialism and Christianity! – to become aware of all of this in the midst of that “delicate air” and delightful landscape and climate of Italy, was indeed a new departure for me.

Carpenter wrote an article “Back to the Wild” promoting social nakedness in nature in 1921 after “swimming wild,” i.e. skinny-dipping, at Lyme Regis in the UK, not far from his own backyard. From the Sheffield Library Archives, “Back to the Wild” by Edward Carpenter from The Free Oxford: A Communist Journal of Youth, October 1921 comes:

There is a strong prejudice…that the uncovered body is not a fit object for decent people to look at! Yet, take it how you will, the prejudice (for I can call it by no other name) is a strange one, and suggestive of something out of joint in the order of our so-called civilisation. That the most elaborate and perfect product of animate creation should be taboo, that it should be forbidden from sight, on no account to be ever seen in public, is an extraordinary dispensation, and one which baffles explanation. 🪐