Like all good anecdotes and inspiration, it came suddenly and unexpectedly. How I ended up receiving threatening telephone calls and angry emails from a Maryland auction house was one of those life events that started simple enough but progressed. All of this led to me writing a novel, Anders Zorn: Unveiled, and to my decision to no longer have a landline telephone, as well as my becoming an art historian. I sometimes wonder if my being a writer leads to my adventures, or if being adventurous makes me a better writer? To be honest, odd things just happen to me, I think because I do things and I see things that others might not.

How, then, did this odd tale of deception and intrigue start?

In 2010, my wife and I decided to visit Sweden to pick up a new Volvo. Their overseas delivery program was great for enjoying both a fun, free trip and a cheaper car. We have picked up seven such cars, some for people I hardly knew. This was one of those times, but the trip was in February. Now, for nakationers, Sweden in February—aside from the sauna or bastu—is a bit too cold for our usual kind of getaway. Abandoning nudity as our goal, we decided we’d go north of the Arctic Circle to go skiing.

After taking our “delivery” in Gothenburg and driving it exactly fifty feet out of the factory, we took the train north to Stockholm to pick up relatives. We arrived a day early, giving us an afternoon to kill. It was there that a whole different adventure started, yet unknown. We decided to go to the National Art Museum, located in one of my favorite picturesque buildings on the Stockholm waterfront. The large banner out front was of a naked woman. My wife smiled and said, “I suppose you want to go there?”

I walked in, remarking that maybe this is a whole different kind of nakation after all. The “Lust and Vice” exhibit, translated as best as I can, featured some very interesting works that the curator had put together that even made some of the Swedes a bit uneasy. The entire second floor was taken over by art that ranged from simple nudes to the erotic, to the pornographic, and eventually to the strange. It was an interesting visit.

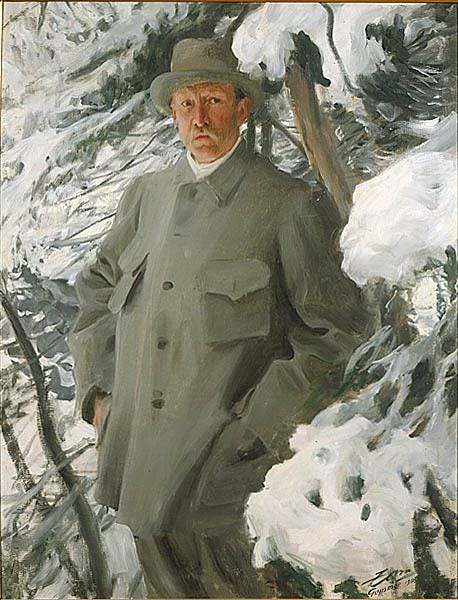

As I made the rounds and then went around again, one artist stood out above all others. It was a classic painting. He was from the same region in Sweden as my family was: Mora in the Dalarna Province. One of the paintings showed a 1908 picture of the Mora Midsommar celebration, one in which my Great-Grandfather could feasibly be included. I looked and looked for him but didn’t see a familiar face. Anders Zorn’s father and my great-great-grandfather’s father, both from merchant class backgrounds, came to Sweden from Bavaria together, sensing opportunity. Zorn’s father died in Finland when he was a young boy (possibly with my ancestor), and his mother remarried a local Swede. Young Zorn was sent to art school after his college education.

Ancestral tensions

To summarize my own ancestry: my great-great-grandfather, Henrik (Henry) Vedelius, went to university and trained for the priesthood, but became disillusioned, joined the Pius movement, and emigrated to America in 1881 to spread the gospel. Still emotionally connected to his homeland, one of his criticisms of Sweden during the Gilded Age was what he saw as the decadence of Anders Zorn’s nude paintings of local peasant women. His religious mission ultimately failed. He married a former nun, who was soon committed to the Minnesota Hospital for the Criminally Insane and died tragically just weeks later. Left with two young children, he became the most educated man scraping by in Wisconsin’s Cut-over. He died a broken man in 1913. His only son—my great-great-uncle Arthur—was later killed in action in World War I in 1918.

My great-grandfather, Wilhelm Danielson, was a mail-order husband who married Henrik’s only daughter. The two were an oil-and-water mix. My great-grandmother was an elitist (though poor), a religious zealot like her father, and a classically trained pianist who played only in church. Her husband was fun-loving, made moonshine, and was happiest naked in a sauna. They’re even buried in separate cemeteries. I grew up running naked across the land they once owned—plus some adjoining tracts my grandfather later bought—and did so for decades, a full century after Henrik’s death, delighting in how much that might have irritated the original owner.

Unlike my ancestor, Anders Zorn had great success and became Sweden’s most prominent portrait artist. By 1900, Zorn was arguably the preeminent Swedish artist of his time. His portrait fees ranked among the highest in the world. He painted three sitting U.S. Presidents, and his 1911 portrait of President Taft remains the official painting in the White House. He famously turned down a $50,000 commission from John D. Rockefeller because it would have interfered with his beloved Midsommar celebration back in Mora—an event he never missed. While examples of his traditional portraiture can be found at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and elsewhere, Zorn is best known today for his nudes.

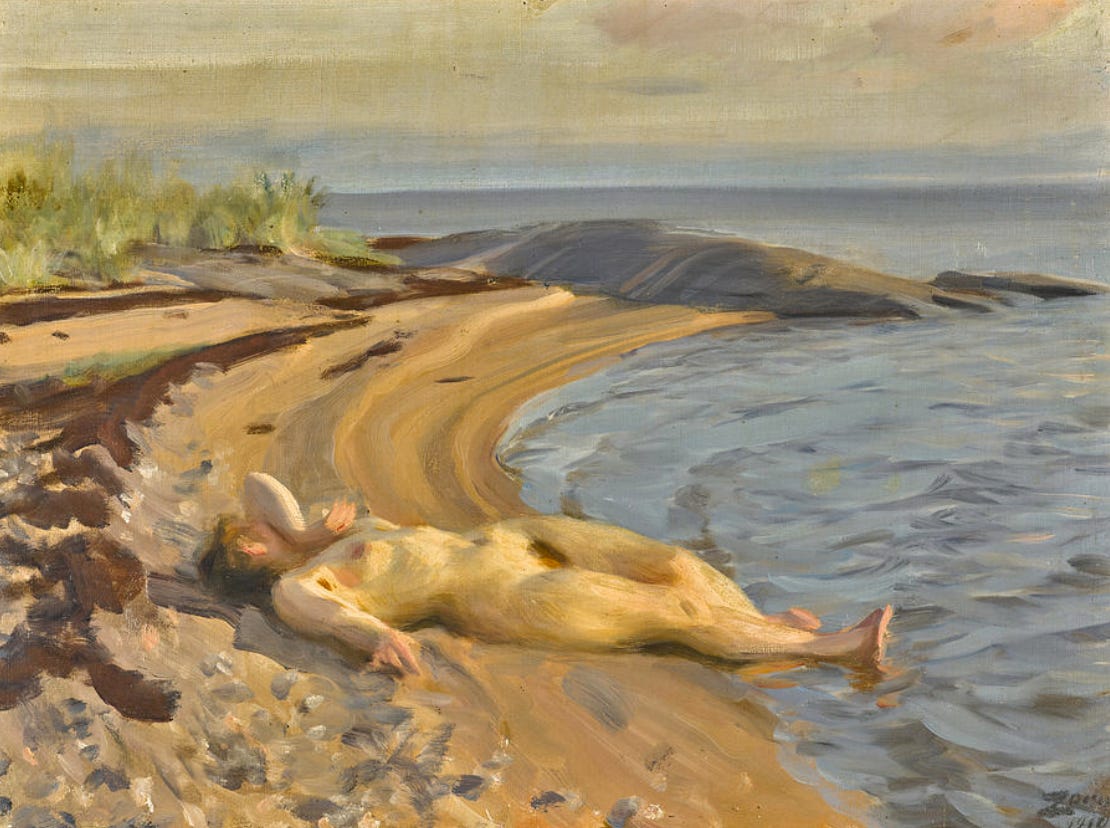

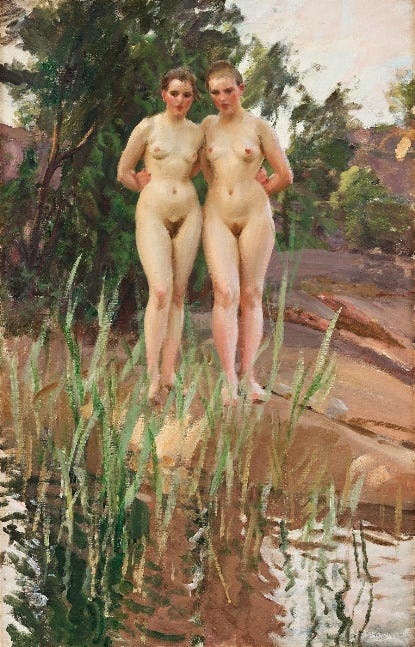

When I see his nudes, it is almost like I can talk to the women, like they are alive on the canvas. In many cases, I feel I even know these ladies like they are old friends and relatives (I probably went to school with their great-grandchildren). I know this is odd, and to be honest, when I visited the Zorn Museet in Mora once, I had to leave; I was overwhelmed. The museum director even came to comfort me. I have only seen one male nude of his, however, and despite this, in my opinion, he captured the essence of what was to eventually become the FKK movement in Europe later on: innocence and comfort in being naked in nature. People have joked that my great-grandmother could be one of the nude models. No, two could probably be great-great aunts of mine. As a result of that emotional recognition, of seeing something both familiar and freeing in his nudes, I fell in love with outdoor nude art, and with Anders Zorn in particular.

Myth and mystery of Zorn

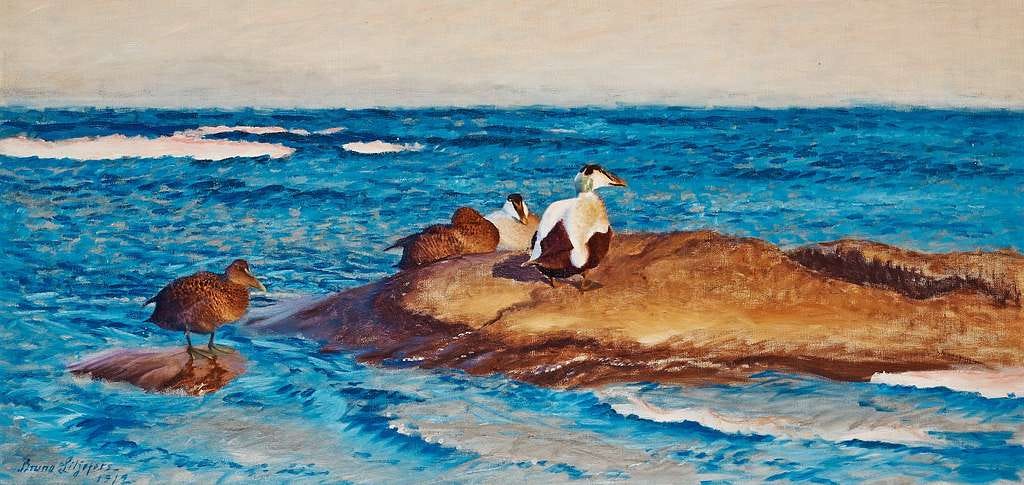

There are many Zorn stories, and it is sometimes hard to know what was really true. Some of it has been whitewashed from history. It is implied that he lived a Bohemian lifestyle. He spent many summers cruising around the waters of Sweden with other artists in tow, men like wildlife artist, Bruno Liljefors (same age and trained together), or others. On one boat trip, with two models, the women made a vow to the pair that they would live naked the entire summer if the men would. Were they the first nudists in Sweden?

The artists painted the scenery, the animals, and the women. Liljefors was never known to ever paint a nude, although Zorn implied he did; possibly he destroyed them after his crazy summers with Anders. One can only guess at the day’s events—nude women, drinking wine, etc. Zorn and his wife got into constant fighting over these sojourns, and whether the artist was saintly or a hedonist, the records never collaborated concretely. Zorn never had any documented children, neither by his wife, Emma, nor from any of the models. Were these young maidens, and Zorn’s illegitimate children, sent with money to America to get away from central Sweden and public scrutiny? Maybe Zorn was infertile? It’s easy to speculate.

One thing that you can appreciate is the wonderful peasant nudes that he left behind, still adorning museums around the world. The best place to see them are the ones in Stockholm or at the official Zorn Museet (museum) in Mora. They are closed on Mondays, so beware.

The Bronze Caper

Personally, now captivated, I went on to expand our own art collection, not with Zorn works per se, as they go at auction for between a quarter to a million dollars each. However, one day while I was tracking down a work on Maria Szantho, a Hungarian artist also with an interesting life at an auction house in New York, I found something that looked much more interesting. It was a bronze sculpture of a naked woman, and on the back, the words “Zorn” and “1910” were etched in the original cast.

Anders Zorn did periodically cast bronzes, and after we switched from looking at the painting to this piece, the owner played it cool. “Well, I don’t know anything about this being a Zorn, I’m Hungarian.” He said innocently. “I got it in Europe from an old man who said he worked as a sailboat crew in Sweden when he was young. I’ve had it for many years.”

He set the hook and was starting to land a fish named Olaf. I demurred enough to get home since he neither took credit cards, and I didn’t have that much cash on me. We eventually agreed to the price of $1500, which he seemed quite firm on, and was one-tenth the going rate of a normal Zorn bronze. At home, I found that similar bronzes had occasionally been sold at auction, and excitedly, I sent the man a check.

There’s an old saying in fishing: just because you hook a fish doesn’t mean you’ll get it into the boat. The same applies to buying and selling art. The very next day, while waiting to fly home out of Newark Airport, I was browsing a Swedish auction site and fell in love with a painting. I started writing a novel almost immediately. Curious about the painting, I emailed the auction curator to ask if they knew anything about the models—one of them looked strikingly like my aunt. He responded that he didn’t, but said the director of the Zornmuseet would be the expert to ask, and gave me her email. As it turned out, it was the same woman I had met in Sweden a few years earlier. For two hours on the flight, I carefully composed a letter in my poor Swedish, aided by a battered dictionary, trying to ask my questions thoughtfully. Feeling proud of my effort, I added a postscript to show off the statue I had just bought.

It took two hours for the reply, and I had not yet arrived home when I read it. In only seven words in perfect English, this international authority darkened my mood. “Olaf, bad news, that Zorn is fake!” I stopped payment on the check five minutes later and penned an email that I had “changed my mind” to the seller. Lucky me!

Everything had worked out, and I had a nice correspondence with a woman at the museum. She even remembered me from my odd reaction to her museum. It turns out she had visited Minneapolis and attended a function in which I had met the King of Sweden. In an “it’s a small world moment,” we apparently sat next to each other, but she was not sure it was me and did not want to be embarrassed if she was wrong. It seems counterfeits are everywhere in the art community. I figured the whole ordeal was over… famous last words.

From fiction to forgery

I published my novel Anders Zorn, Unveiled in 2015. It became my best-selling eBook, but with my royalties around $0.13 per copy on Amazon, there was never going to be a pot of gold at the end of that rainbow, no matter how many I sold. I think most people bought the book because of the cover. It actually has very little to do with Zorn. I never marketed the softcover version much. The story follows the fictional, illegitimate great-grandson of Zorn and one of his models, who ends up on a life-changing adventure.

About a year later, I got an email from someone who bought the book. They apparently took me as an art expert on Zorn and wanted me to “authenticate” a bronze they were thinking of bidding on at auction. I said I was not an expert, far from it. They sent me a picture of the statue. It was probably the exact same piece I had bid on that was listed in an auction catalogue in New York as an original Zorn! I sent them a copy of the email from Sweden that I had. I also forwarded my letter from the director to the auctioneer. The item was pulled from the auction the next day. Reputable auction houses will not knowingly sell fakes, as it ruins their reputations. I was, however, a little disappointed by the lack of provenance that auctions seem to require. It wasn’t difficult to determine that this was a fake.

The same statue later showed up at an auction house in Maryland. I repeated the process, but this time the auctioneer was not very receptive. He even threatened me for “tampering with an auction.” I threatened back, giving him the direct telephone number of the museum director in Mora, Sweden. I felt I was on the moral high ground. He persisted that it was none of my business.

I never knew if he called or not; they eventually changed the listing to “attributed to Anders Zorn” and refused to respond to my further emails. It was then that the original “Hungarian guy” I’d encountered started to threaten me, first by email, and then by telephone. He suggested he’d charge me with trying to pass a worthless check. I had to disconnect our landline telephone.

Luckily, South Dakota is a long way to go to settle a score. I cc’d him a letter I sent to a few auction houses as a warning with a copy to the FBI. I never heard from him again, and the statue or a clone appears from time to time at various minor auction houses, but I guess the adage buyer beware is applicable, and I do not bother saying anything. It probably isn’t any of my business anyway.

Zorn’s final chapter

Although largely ignored, Zorn was an enthusiastic photographer. The full extent of his work is believed to be buried somewhere in the Swedish archives.

With the outbreak of World War I, Zorn turned to using the riches his painting had earned for the greater good: in 1915, he donated two aircraft to the Swedish armed forces, and in 1917, he gave one of his properties in Mora with a capital sum to found the Zorn Children’s Home. The previous year, he had exhibited with Carl Larsson and Bruno Liljefors at the inauguration of the Liljevalchs Konsthall on Djurgården Island in Stockholm, which is now owned by the city.

In 1919, Zorn made an endowment to the Swedish-American Foundation which formed the Zorn Award. Early the following year, his mother died. He was then finally elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts, and he continued his philanthropy by funding a chair in art history at Stockholm University. Then, on 22 August 1920, Anders Zorn died at the age of sixty; his widow, Emma, died in 1942. Dying without children, he willed his property, his extensive art collection, and the rights of all of his paintings to the Swedish people in the same way Tolstoy had done, it was a way to give back for what the people and mostly the local women of Mora and Falun Sweden had done for him.

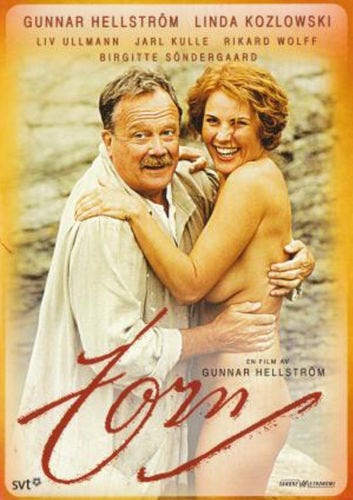

There is an excellent movie on Zorn (in Swedish), done by Swedish TV, that might as well be a naturist movie. It is a lot like “Sirens” (a movie based on Australian artist Norman Lindsay) in that the women are frequently depicted naked. My copy is European format, and I am not sure if you can find it here in North America, but it is a good story.

It is quite likely that I shall never own an original Anders Zorn work of art. His lithographs are more affordable and run a couple thousand dollars. A coffee table book of his works was even cheaper. I love to get lost in the pages. They make me smile as I drift off daydreaming, thinking of my wife and me enjoying ourselves naked at similar spots in the Swedish countryside back in the day. Maybe now, after reading about Mr. Zorn and getting a taste of his impressive art and my crazy tale of my intrigue in the art world, I can share a few of his paintings with you. You may even see naked paintings of my ancestors…I only wish I knew for sure. Some might find that uneasy, but I think it would be grand. 🪐

I've long admired Zorn's work and I've wished it was more readily accessible in the U.S. Do you happen to know of anywhere in the states with a good collection of his works?

Olaf, Thank you for an informative and easy to read article. I remember being at a meeting in Washington DC and coming across an antique shop on my way back to the hotel. In the shop, in a dusty corner, there was a lovely nude sculpture. It was cast copper and on her butt was stamped MAILLOL. I called my wife in Alaska, as we had been collecting nude artworks. It was $500 and while I really, really liked it, the price was not in our budget at that moment. She responded, if you really like it, get it, you may not find another piece that moves you in such a way. I still have that sculpture and this story albeit she is gone.

We later took it to an Antique's Roadshow in Anchorage. Aristide Maillot was a noted sculptor so we were excited to hear the appraisal. It was concluded that the sculpture was not an original Maillot, however the art historian did state that it very likely was from his studio, being a study piece or serving as a model for students. The level of patina had secured its timing to the artist. We still enjoyed having it and displaying in a spot of honor.

We liked collecting nudes where either we knew the artist or the model. It is wonderful how you can look at Zorn's work and genetically relate to the models. That is a very personal connection. It is also wonderful that Zorn gave his life's work to the people of Sweden, who had given him so much. Lovely in many ways.

As a stone sculptor who has exhibited pieces and a buyer, the one phrase I most often hear is "buy art that you really like to look at."