The first “clothing-optional” event in America

The forgotten 1927 swim that made headlines, challenged modesty, and may have coined a naturist term

It is odd how two independent tracks come together. I have spent about three months chasing sources deep in the bowels of American history about the real beginnings of nudism. All of this has a tendency to throw one into the weeds, and you can easily be bogged down. The standard date of late 1929 bothers me. First, one needs to examine definitions. This mostly boils down “What is a nudist activity” versus an “activity done in the nude?” To be honest, I have not come up with an answer. I was busy writing either a book, a chapter in something, or an article here on the “St Petersburg Solarium” when Tom Perrin posed a question on the American Nudist Research Library Facebook page:

“When was the first documented use of the term ‘Clothing Optional?’

The question became an interesting distraction to my ongoing project. There were a few responses on the Facebook page until I noticed it. One had said sometime in the Seventies, and another referenced at some point in the Fifties at Lupin Lodge. I knew it was a much older term, but how old?

The term “clothing-optional” predates its nudity definition by at least a couple of decades, as it was used in military speak, as best as I can define it, “wear what you want.” It is documented in British and Welsh newspapers around the turn of the 20th Century, and I think the term was used enough that it is not worthy of my efforts to source them. It was first used in the US press in Indiana on July 10, 1913, appearing in newspapers in Waterloo and Indianapolis independently, two months apart. These articles described two different military field days, both the ½-mile run and the 100-yard dash, which could be “clothing optional.” This author doubts you could show up naked, but I assume you could wear shorts and a light shirt.

But when did it mean being naked? When Tom Perrin asked his question, I had some writing projects saved up, but unfinished. I had stored an AP newspaper article from December 10, 1926. I looked at it again. When William Wrigley Jr. proclaimed the day before that his “Wrigley Ocean Marathon” would be “Clothing Optional.”

It is my belief that the definition of the term “clothing-optional” to imply nudity was born. My answer for ANRL was that it was coined by William Wrigley Jr. (Chewing Gum Magnate) and owner of the Catalina Island Company on December 9, 1926, in order to promote a race which would highlight his island as a winter vacation destination.

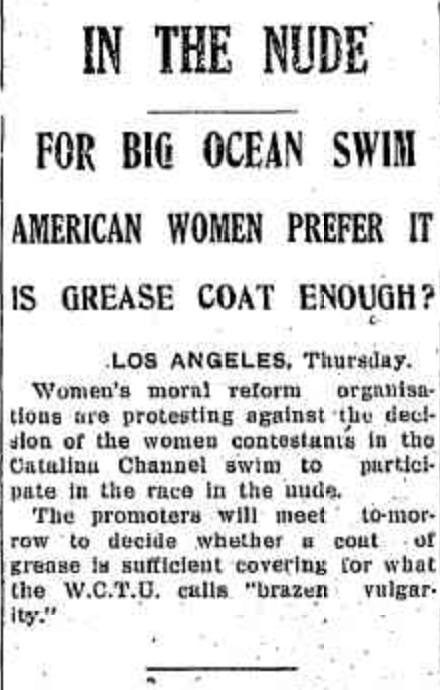

Before you state that his comment does not imply that one could swim the 22 miles nude, think again. There are countless articles about this one-of-a-kind event that collaborates with nudity, I will just include a single one from Australia.

It was a New York swimmer, Charlotte “Lottie” Moore Schoemmell, who made the request to Wrigley, contending that a suit would hinder her progress and chafe her body. The committee agreed, and many others followed her planned attire.

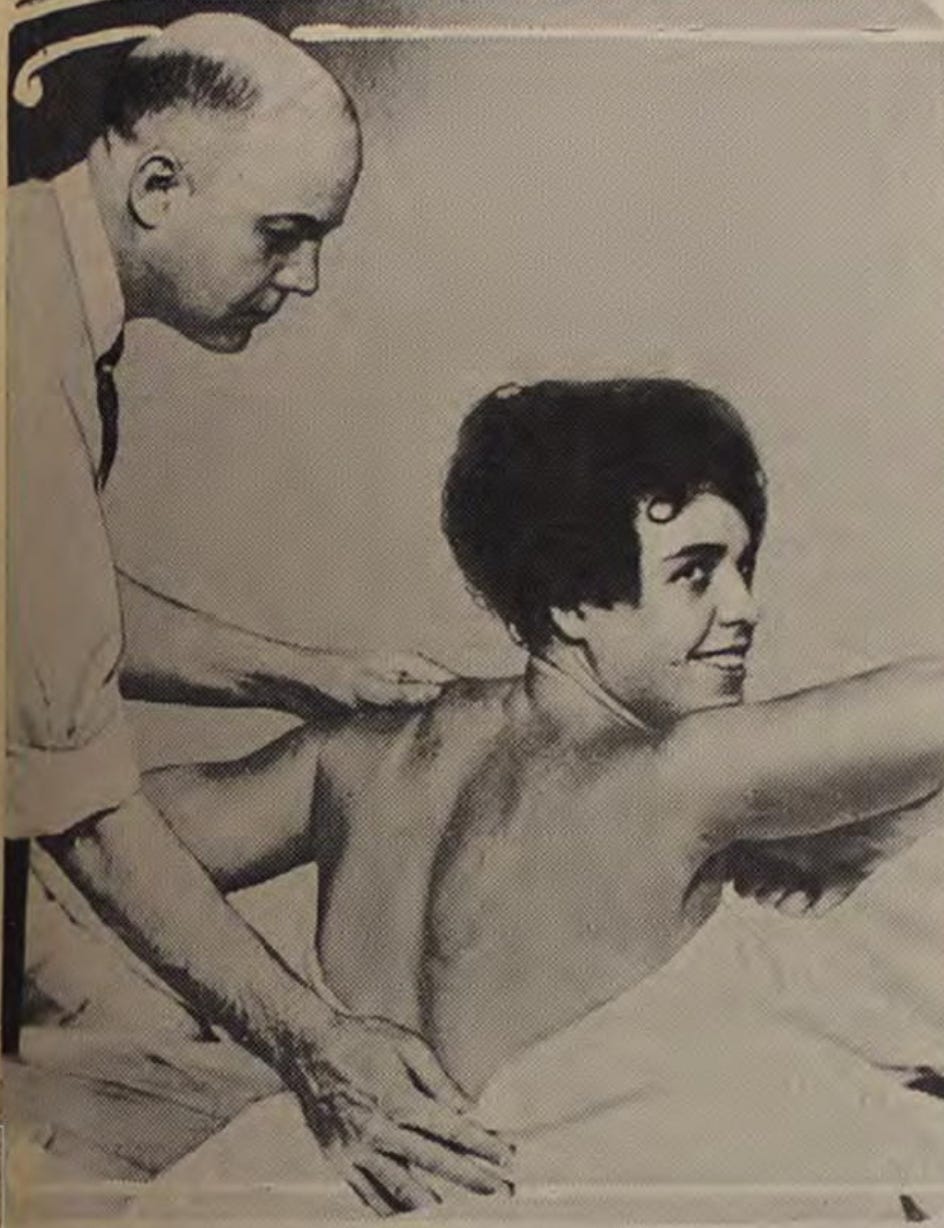

So, what was this event, and why did anybody care? In 1926, Marathon Swimming became all the rage when an American, Gertrude Ederle, swam the English Channel (21 miles) on August 6, 1926, breaking the existing record by 2 hours (it was previously set by a man) wearing a controversial two-piece swimming outfit covered in grease. She received a ticker-tape parade in New York due to her achievement. Suddenly, everyone wanted to do marathon swimming.

Sensing opportunity, that fall, Wrigley decided to organize an event to swim the Catalina Channel, a one-mile wide crossing (22 miles) on California’s west coast. He offered to pay himself the $25,000 cash prize to the winner, and smaller prizes to the female winner if they did not win the whole thing.

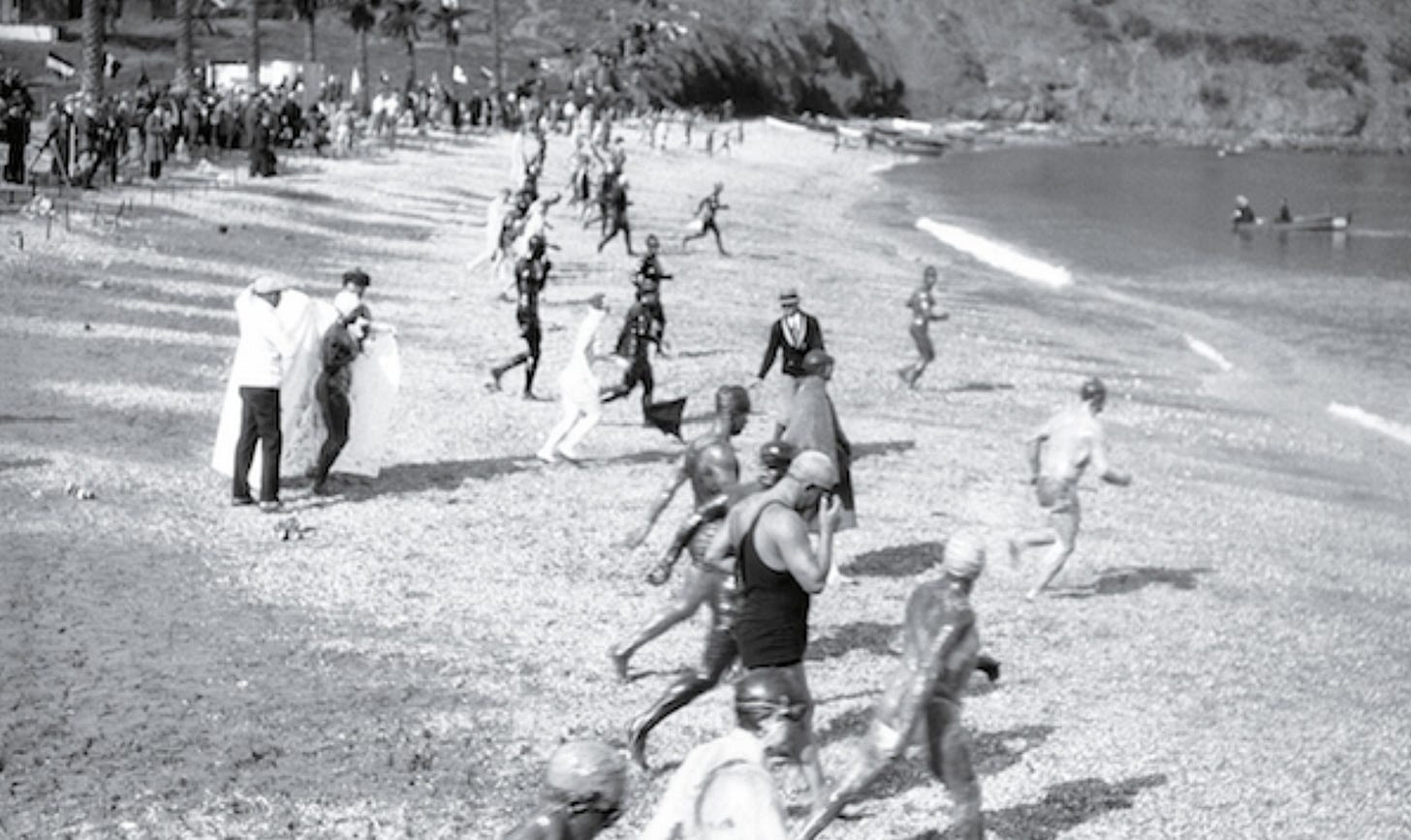

149 people entered. Over 100 swimmers, covered in grease, animal fat, and oils of all kinds, thought to have thermal properties, started in the water at 11:21 am on Saturday, January 15, 1927. Mack Sennett’s famous “Bathing Beauties” (who were definitely clothed) were on hand for the big send-off.

Concerned about the safety of swimmers, Wrigley implemented a number of safety requirements. Each swimmer was required to have a boat with one sanctioned official on board. A power boat could not get any closer than fifty yards; one half hour before the race, each winner had to turn in a certificate from a doctor stating that the swimmer was in good physical condition; all boats had to have the swimmer’s number painted on the side, and the number rigged so that it could be seen at night. In case of illness, an attack, or possible drowning, Mr. Wrigley transformed the Catalina steamships (the ferries that shuttled everyone back and forth to the island) into temporary hospital ships.

The race started at a beach in Catalina at Two Harbors. 15,000 people gathered in San Pedro and awaited the finishers.

As for the race, almost all swimmers had given up at various points during the race. The water temperature in the Catalina Channel was reported to be in the low 50s. No one got attacked by sharks, and no one drowned. As darkness approached at the end of the day, and with a full moon to help light the way, only twelve swimmers remained.

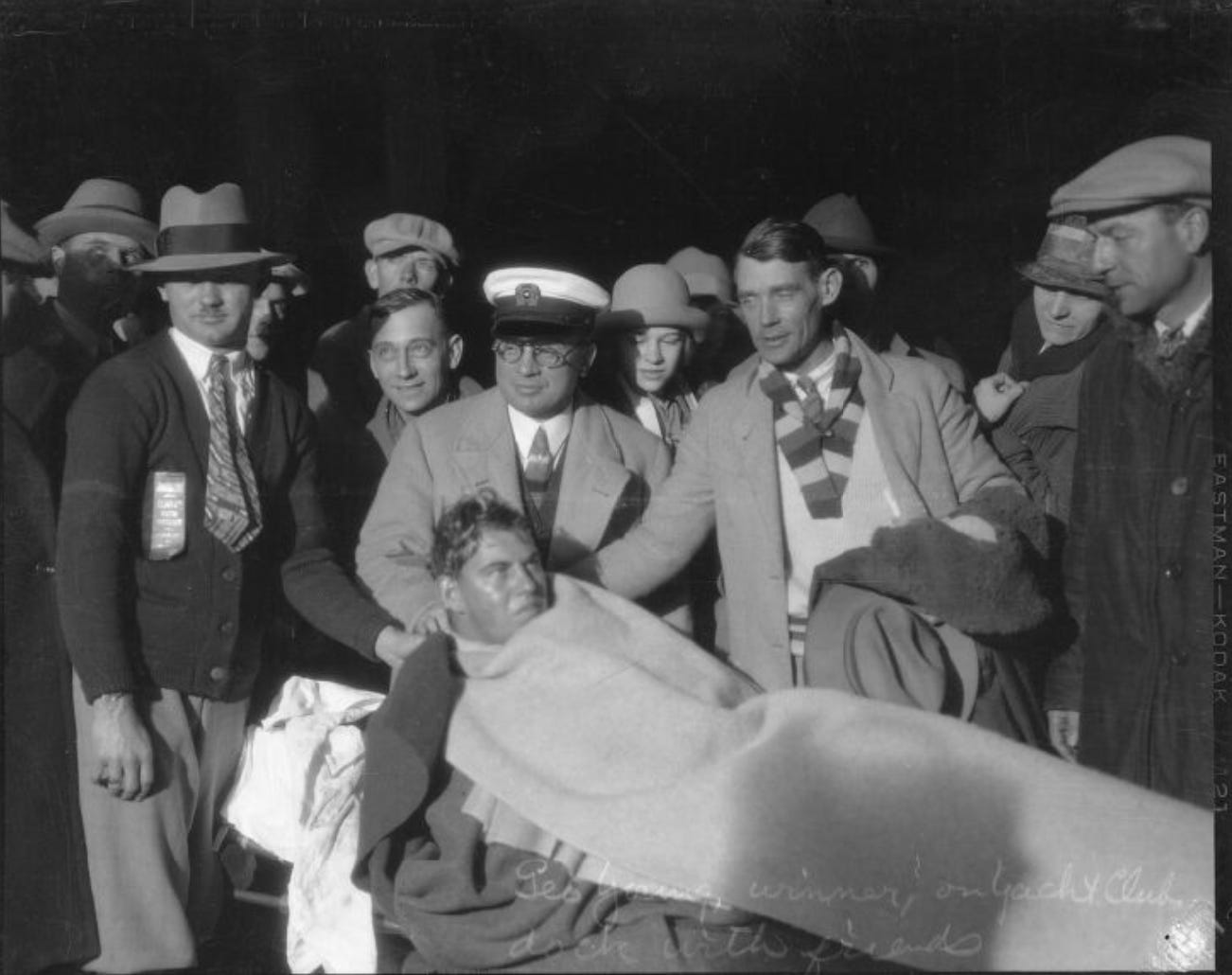

From the start, George Young, a seventeen-year-old Canadian amateur swimming champion, had taken the lead. George had come to Catalina from his home in Toronto, with just $135, money his crippled mother had taken from her savings. By 2:30 am, Young could see that the prize was within his grasp. As he approached the shore, the judges waded out to shake his hand. At 3:05:30 am, Young emerged from the water having spent 15 hours, 44 minutes, and 30 seconds on his journey. 15,000 spectators were on hand for the finish. Boat whistles, auto horns, and human cheers joined in the chorus as flares of Roman fire lit the scene.

When Young emerged, two remaining competitors, Margaret Hauser and Martha Stager, were still in the water, both a mile from the finish. They were pulled out, and although they did not finish, Mr. Wrigley awarded them $2,500 each for their valiant effort.

Young later recalled, "We put a covering of graphite over the grease before I put on my bathing suit to help keep out the cold... I had taken off my bathing suit when I was two and one half miles from Catalina, and I forgot that grease and graphite were my only covering as I rose out of the water."

Although the swim generated lots of publicity for the island, with safety concerns in mind, Wrigley decided not to “tempt fate” again, making the swim the first and final Wrigley Ocean Marathon.

It is always sort of funny thinking about all of the faux morality back in the day, not that Catalina was ever a naturist mecca or even a destination. I assume naked women paraded around most of the pools of the “gilded class” mansions there back in the day, probably even Wrigley’s. One of the first things I saw when I disembarked from the ferry boat on Catalina was not the spotted dove I had come over to see. It was this mural on the Avalon Theater building. This was the first photo I took on the island.

So today, we have learned three things: when the term “clothing-optional” was first used, and the first clothing-optional swimming marathon in America. I have also identified the location of the first anatomically correct mermaid placed in public view. Speculation, possibly, so I await corrections to these assertions. I am a big fan of mermaid art, so any leads to alternatives would be appreciated. 🪐

Thanks for another great article. Bernarr Macfadden held a beauty / physique competition in NYC where the participants posed nude before the judges (with supposed holes cut through the privacy curtains for high paying viewers) prior to this open to the public swim. The Common Sense Club had Camps in every one of the 48 states by 1919. It was the first organized nudist effort in the USA. Informally, they are documented back to 1905. Social nakedness among friends and family, including descriptions of nude hiking, camping, doing board games indoors, and sun, air, and surf bathing were written about in 1904 by John Russell Coryell. In 1902 “Clothed With The Sun” was the newspaper of the Home community in Oregon where clothing was optional when swimming or sunning along Puget Sound. It is great to discover these early pioneers of social nakedness right here in America.

Thanks Olaf for this wonderful history lesson! It’s so fun to learn about the history of social nudity, organized or not, both in America and beyond. I appreciate you, @The Nudist Archive, @Evan Nicks and many others for the stories you share on Substack. I can only imagine the hours/days/weeks of research each article requires. I hope the effort is as fun and rewarding for you as it is for me to read it 🙏🏻