Turned away at the gate

Matthew Bullock, Loretta Gueye, and the fight to integrate American nudism

“I thought nudists would be more open-minded.”

—Loretta Gueye, Jet Magazine, July 14, 1966

This one came without warning. I was working on a piece about naturist advertising and digging into New Jersey’s nudist history when I stumbled across a story that stopped me cold—one that deserves to be shared.

Judge Matthew W. Bullock Jr. may have been the most important Black man in the history of Northeastern nudism. Loretta Gueye, you could say, was its Rosa Parks. And yet neither appears in the “nudist hall of fame.” Bullock has a short, hard-to-find blurb in the American Nudist Research Library. Gueye? Almost nothing. This is my imperfect attempt to give them a little credit.

Matthew Bullock’s fight for inclusion

Back in the Sixties, Bullock was an African-American, Harvard Law-educated lawyer based in Philadelphia who had discovered nudism back in 1938. He graduated at the top of his class in 1940 from Bowdoin College, completing his undergraduate degree in three years. He also helped the ACLU, which his father had helped to found. The elder Matthew Bullock was a legal scholar, Black football pioneer, war hero, and even a Baha’i faith pioneer in North America—and the son shared his zealotry for fairness.

While in college in 1938, Bullock read Among the Nudists by Frances and Mason Merrill and realized that was for him. He skinny-dipped at YMCAs in the Northeast as a young man, but had to delay deeper involvement—he had law school, got married, started a family, and moved to Philadelphia. In 1950, he sent a letter to Sunshine Park, responding to “Uncle Danny’s” call to enjoy the sunshine au naturel. Not wanting to be turned away at the gate, he disclosed that he was Black. The letter went unanswered, so he never went.

In the middle of the Civil Rights era, in 1965, a friend got him an invitation to a social event where Zelda Suplee—owner of Sunny Rest in the Pocono Mountains—was present. That meeting led to a visit to the camp with his wife Etta and two other couples, one of whom were members. They integrated the camp, if only for a day. A couple of weeks later, the members they had visited with advised that Matthew and Etta would not be accepted as members. The reason given: Bullock was “too assertive” and might not take racial insults lying down. They didn’t want any trouble.

Another member of Sunny Rest, upset by the rejection, was determined to find a nudist resort that would accept the couple. A few weeks later, he took his two daughters (ages 12 and 18), along with the two other couples who had gone to Sunny Rest, to Circle H Ranch in New Jersey. His wife didn’t attend due to being called out of town on an emergency. Everyone reported a very enjoyable time, and he later said they met many friendly and accepting people. The owners, Lucille and Earl Hansen, told them they would be glad to have the family join the resort.

However, just a few hours later, the offer was withdrawn. Lucille pulled one of the women in the party aside and told her someone had complained that Matthew had spit in the swimming pool. He denied it then—and decades later, denied it again in his biography. A couple of weeks later, the invitation was reinstated after the young couple who had reported him resigned. It was assumed the Hansens had taken a lot of heat.

Then came another roadblock: after a couple more visits, they were told they could not return together since they were not “legally” married. This despite the fact that in 1965 they would have been considered common-law married in many states, and despite the fact that Etta was the mother of his two children—and that several other couples who regularly visited the resort were not married to one another either.

Historian Professor Carl Hild wrote in a 2002 issue of N Magazine that Lucille and Circle H Ranch represented “naturism with a social conscience.” He does not, however, discuss race relations at Circle H. This isn’t meant to throw Dr. Hild under the bus—just to point out that things are always more nuanced. Regardless, Bullock’s visit to Circle H marked the first documented integration of a New Jersey nudist park.

One should not be confused by a 1964 tabloid article that claimed a Black man had integrated a nudist camp at Sunny Grove, New Jersey, as no evidence exists that such a park ever existed. In fact, the secretary of the American Nudist Alliance (which owned the Flamingo Country Club in Delray Beach, Florida) sent the article to the chief of police in Sunny Grove, only to have it returned—because no such place existed. Both he and I believe the article was fictional prose. As of early 1965, the only integrated nudist parks known to this official in the East were Bruins and Zoro. Even though Bullock’s early attempts ended badly, his visit to Circle H remains the first documented case of a Black man or woman visiting a nudist camp in New Jersey. He should be considered a pioneer of integrated nudism.

Loretta Gueye and the Sunshine Park standoff

Attempts to break the New Jersey color barrier continued into 1966, which brings me to our second hero. Loretta Gueye, a married, 27-year-old African-American secretary from Brooklyn, had practiced nudism in Europe and Africa for seven years until she got married and moved to New York City.

She picked up the mantle for nudist civil rights when she—along with another 27-year-old secretary, her young son, and her niece—drove down from New York on May 28, 1966, after being invited in writing to attend Sunshine Park. Despite the lack of any official “anti-Black” policy, when Oliver York, the psychologist owner of Sunshine Park, turned her away, he unleashed a firestorm. If he had been trying to generate a public relations nightmare for all of nudism, he couldn’t have done it better.

Lucille Hansen of Circle H once wrote that nudism in the Sixties was controlled by “old” and “out of touch” men. In this case, she seems to have been right. As the Civil Rights era progressed, neither the American Sunbathing Association, the National Nudist Council, nor the American Health Alliance appeared to have any thoughts on the matter—let alone guidance. When the story exploded in national newspapers, there’s no evidence any of them issued a rebuttal. There was nothing of note in the nudist publications either. Since ASA had owned Sunshine Park for a long time, many textiles assumed Sunshine Park’s actions reflected ASA policy—even if the association had by then moved its offices elsewhere and sold the property.

Gueye filed a written complaint, alleging a violation of New Jersey civil rights law, and wrote a letter to Senator “Pete” Williams, who demanded an investigation. York offered a feeble excuse, claiming the KKK was active in southern New Jersey and he didn’t want to provoke them—though I doubt the Klan had much time for nudists, white or Black. In the end, he called it a “misunderstanding” and invited her back. There’s no evidence she ever returned. But the article appeared in over 500 newspapers, The Black Panther’s Militant, and in Jet and Ebony magazines.

Institutional silence and quiet reckonings

As things go, Sunshine Park eventually came back around to Matthew Bullock. A full 17 years after he had sent his unanswered letter in 1950, Oliver York finally responded in 1967. “Come back!”—well, not exactly in those words, but he did invite him. I suspect he was hoping for good PR. Bullock declined. He was running for judge and didn’t want the attention. It remains unclear how Sunshine Park ultimately integrated.

The Hansens, for their part, saw the light—at least partially. When they redid their brochure, they subtly included a Black woman in the photos.

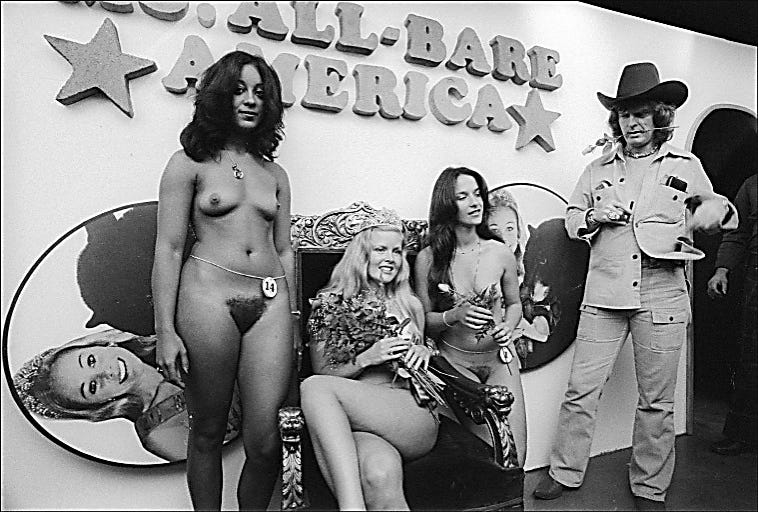

Years later, in 1974, the club hosted the inaugural “Ms. All-Bare America” pageant (a somewhat cringe-worthy event hosted by Don Imus). A Black woman from South Carolina was third runner-up. Could that have happened in the Sixties?

So, there we are. Loretta Gueye’s name didn’t appear in another national newspaper until the Philadelphia Inquirer revisited the Sunshine Park story in 2023. Did she ever get to practice naturism again? I don’t know. But the firestorm she started brought change—subtle at first, but real. She should be remembered as a hero.

Matthew Bullock later served as a judge in Philadelphia, eventually moved to California, and became a founding member of Southern California Naturist Association (SCNA). He lived a long life and died a practicing naturist. Maybe he couldn’t tolerate the spotlight like Mrs. Gueye could—but he, too, should be remembered as a hero. 🪐

Olaf, Thanks for an insightful article. While working at Circle H in the late 1970s I did hear stories of integration and conflict. Lucille and Earl were always walking the line as the owners to be inclusive and not loose existing members. The fact that Lucille was half Native American made her well aware of discrimination. I do not mind the mention, additional information, and commentary as with most research it requires first searching, then re-searching, then more re-searching, always moving toward the facts that make up the truth. Thanks for honoring Loretta and Matthew as well as the kind words for Lucille, my "nudist Mom".

A very good article. It is sad that we can't live together WITHOUT discrimination based strictly on race.