Targeted nudist advertising

Exploring the unique history of advertising in nudist publications

In reviewing tens of thousands of nudist and naturist publication pages over decades of research, this author has been absolutely astonished at a recent discovery. The companies that typically advertise in these publications tend to have ads that could fit into any popular publication. However, the one found may be unique as an ad just for nudists.

The evolution of nudist advertising

A century ago, the proto-nudist magazines dealt with physical fitness. The focus was on physical development through publications, equipment, and places. There were hair products, skin conditioners, little pills, and all kinds of elixirs that we now know contained all kinds of dubious chemicals and drugs. Products to enhance one’s capacity to get a good healthy tan, as opposed to those today to offer the best protection from the harmful rays of the sun. In addition, there were books and pamphlets to provide the latest information on a myriad of topics that related to well-being.

There were also sanitariums that offered electrical stimulation, steam baths, sun lamps, and, of course, healthy meals without the influence of alcohol or tobacco. There were guides on how to chew properly for the best digestion. There were posture devices to help you keep the shoulders back and feet arched, as well as to address hernias. The ads were often written in a hyperbolic style, greatly overstating the potential or breadth of benefits.

The first nudist magazines mostly advertised places. Readers were invited to take a short trip to a paradise where clothing would not be required, and the sun, air, and water could be enjoyed in great freedom. Hardy basic meals were often mentioned as being available for very low prices. This was particularly so during the Depression. More recently, ads for photographs, videotapes, CDs, and websites have become popular. These were ads mostly to attract attention from those already interested in social nakedness.

There are ads that some consider odd for magazines that cater to those whose desire is to go without clothes and adornment. Why market fancy boudoir clothes to nudists if this really is a non-sexual family activity? The towels, hats, drink cozies, and even logo-encrusted t-shirts and outfits make more sense. Then there are the body jewelry ads for parts that are only exposed when naked but appear to draw attention to those parts of the body that are being promoted as being normal. This, too, appears a bit contrary to some of the tenets of nudism and naturism. These dangly bobbles bring additional attention to particular body parts, brought similarly by skimpy swimwear or suggestive garb. Well, it is called marketing.

I have not seen ads that promote buying this vehicle to get to your favorite nude beach or naked hiking trail. An irritated Tribal friend has long complained about how accepted the Jeep Cherokee has been for decades and even quipped, “What about if it was called the Jeep Jew, would anyone mind?” Two wrongs do not make a right. Perhaps we could see the Ford Free Beacher, the Nissan Naturist, the Suzuki Skinny Dipper, or the convertible Tesla Top Free.

I have seen ads for strapless footwear. One is basically pads that stick to your feet and would likely collect a great deal of sand and gravel as well. Also, there are all kinds of sandals that are presented, some to be worn with socks or others specifically for bare feet. Over a century ago, both Edward Carpenter in the UK and Bernarr Macfadden in the USA promoted wearing sandals as part of getting back to nature. Physical Culture had numerous ads for sandals. However, these were really for everyone, not just the naturists.

Upon reflection, these ads might all appear in any travel or sports magazine, except perhaps the body jewelry ones. What struck me recently was an ad that was not only marketed to nudists but was developed specifically for nudist women and targeted to them in their own publication. This is remarkable and unprecedented. If any researcher or reader has found anything like what I am about to discuss, this author would certainly like to know about it.

Advertising to nudist women

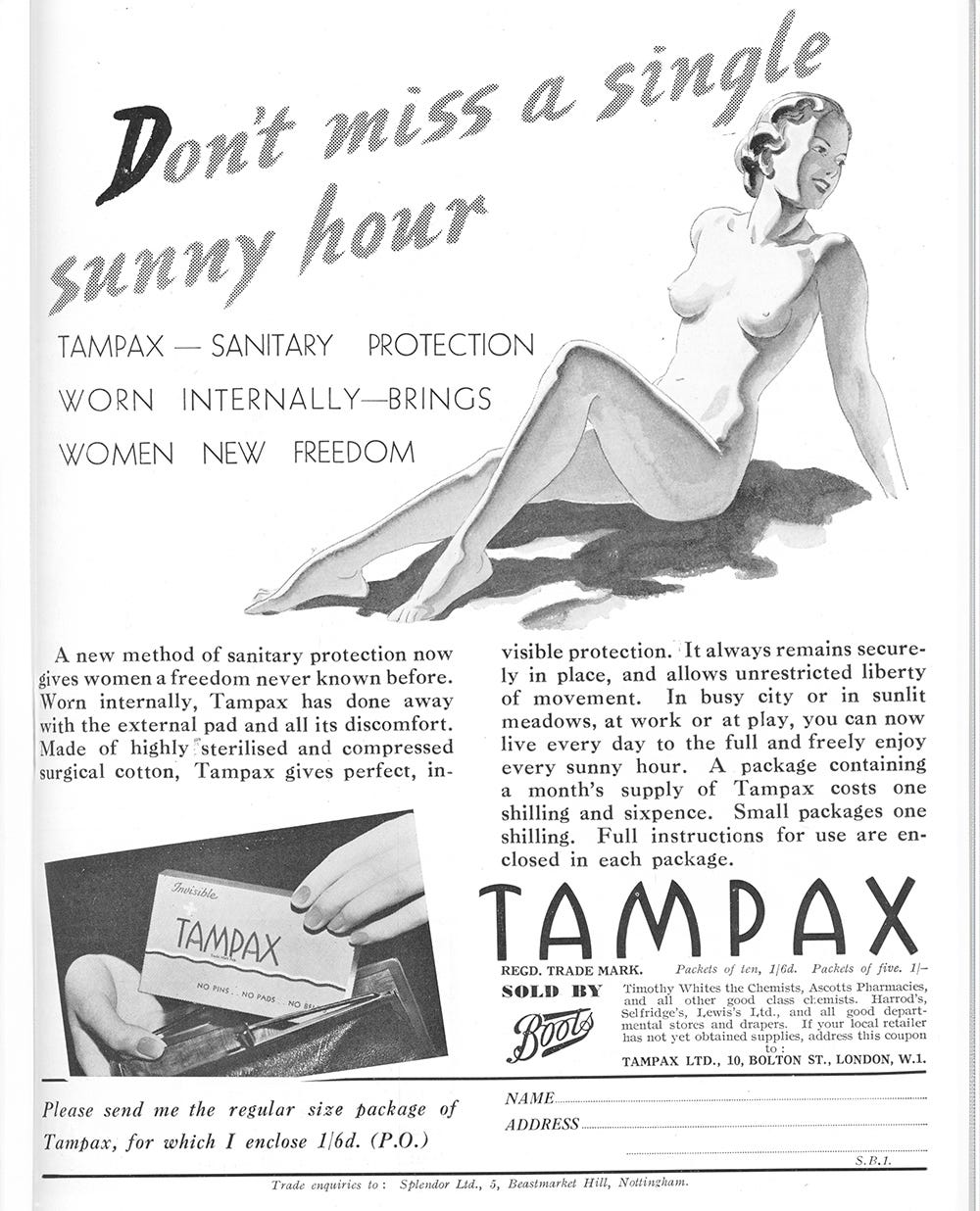

Back in the spring of 1938, a full-page ad appeared in Sun Bathing Review out of the United Kingdom. This magazine had been the official journal of the Sun Bathing Society from 1928 up to 1936, when the editor, Notley French Barford, closed down the Society. He continued to edit the Review until 1938. There, in two-tone print, in large hand-drawn font, was “Don’t miss a single hour,” with a nice drawing of a clothes-free young woman. The top half of the page was both eye-catching and positive in its implied message of enjoying every minute in the sun while you are nude. Wonderful marketing!

Then, there is text to describe the product being advertised. The headings include “New Freedom.” In the narrative are “invisible protection,” “allows unrestricted liberty of movement,” “in sunlit meadow,” and “you can now live every day to the full and freely enjoy every sunny hour.” These are very positive statements about this great product that clearly is being targeted at the women of the Sun Bathing Society. This is a marketing campaign specifically for her. Amazing!

At the bottom of the page is a photo of the product in its commercial box and information on where the product can be purchased. If the reader cannot find the product at their local ‘chemist’ (pharmacy), then there is a form that can be used to obtain the product through the mail. The company was making the product not only attractive to use but also easy to obtain. These were more incentives for buying this product.

Tampax needs to be commended on this very specifically designed piece of marketing. In attempts to do just that, the Tampax company was contacted both here in the USA and in the UK. In addition, the 1937 marketing company that was used, McCann Erickson, was contacted as it is still around. Unfortunately, the current representatives had no information about this nearly 90-year-old advertising campaign.

A history of the tampon

Perhaps there may be other clues to be found in the history of tampons. In 1929 while he was traveling, a female friend in California told Dr. Earle Cleveland Haas of Colorado that she addressed her menstrual cycle with a sponge that she inserted, removed, washed, and reused. Being an inventive physician, he had thoughts that perhaps there could be a better way than having to use fingers to push an irregular, not-so-sanitary sponge, up the vagina, in addition to then having to use the fingers as tweezers to reach up and remove it once it was soaked with menstrual blood.

Dr. Haas worked on his idea of not only developing a one-use cotton-based product but also an applicator that would allow the woman to more easily insert the absorbent material, but that it would also have a string for convenient removal. It took a couple of years to get the product to meet his specifications, and in 1931, he submitted the patent for a “Catamenial Device,” the modern telescoping cardboard tube applicator tampon. It took two years more before the patent was awarded in 1933.

Gertrude Tendreich, aka Gertrude Voss Schulte-Tenderich Sears, was born in Germany in 1890 as Gertrude Voss. In 1911 she married Ernst Schulte-Tenderich. He moved to the USA in 1923 and settled in Denver, CO, where her two brothers lived. She followed ten months later, in 1924, with their two children, Josef and Maria, along with her widowed mother, Gertrude Voss. Gertrude became a naturalized citizen in July of 1933. On her citizenship application paperwork, she listed herself as “business woman”—a bit unusual for 1933, but a sign of what was to come.

Dr. Haas lived in Denver, CO. Gertrude Tenderich learned about his endeavors and saw the potential for this product. In 1934, she started manufacturing his tampons on her home sewing machine, using the compression machine that he had developed to pack them into the tubes. She later hired additional women to produce the items, which were distributed locally in Colorado.

In 1936, she purchased the patient and the product name “Tampax” from Dr. Haas for $32,000 and went into large-scale manufacturing, hiring business, manufacturing, and advertising expertise. The name is a combination of the words tampon and packs, which was the term for menstrual pads—tam packs = Tampax.

A unique marketing position

Tenderich also hired McCann Erickson Marketing to promote this new product, which would offer women much greater freedom from wearing large, bulky, restrictive external pads held in place with pins, straps, and belts that frequently did not do the required job. Very soon, Tampax was available internationally.

As the advertising firm was contracted in 1937, and the naturist ad was in the spring issue of Sun Bathing Review in 1938, it was in the vanguard of Tampax publicity. Someone, likely at McCann Erickson, knew that the nudist movement was rapidly expanding in the 1930s and that participants wanted to enjoy every single hour of sun when the opportunity arose. Being on one’s period could remove that opportunity for full body exposure to the sun as well as being tied up with awkward belts, pads, and clothing that also kept women from being able to swim. In addition, this product allowed women to address their cycle without having to necessarily announce it to the entire world.

Gertrude Tenderich, a German immigrant to America, a hard worker making the first tampons on her own sewing machine, and an entrepreneur seeing the value of the produce, was able to scale up her home-based business to the large international corporation Tampax. Had Gertrude grown up around nudism in Germany? She became an adult and lived in Germany until 1924, so she very likely did have some knowledge of and perhaps experience with the Free Light Movement. From two dates we know that she and Ernst were a bit more liberal than many at the time. Their son Josef was born 27 January 1912, just five months after their marriage on 19 September 1911.

Did she know that active women wanted this type of internal sanitary product? She was an entrepreneur and was quite active herself. When women took jobs during World War II to help the effort, being able to work actively during their monthly cycle gave the product a great demand. The war also put a demand on materials for bandages, so the machines and personnel used to make tampons were diverted to make dressing for the forces. Tampax actively contributed to the war effort.

As the marketer said, this product would allow “New Freedom” through “invisible protection.” It “allows unrestricted liberty of movement” for all kinds of physical activities, be they indoors, in a pool, or “in sunlit meadows.” This ad targeted each naturist woman so she could “now live every day to the full and freely enjoy every sunny hour.” This all in 1938. This author’s grandmother might have seen these ads, and they are still as current and positive today.

Remarkable! 🪐

This author would be very interested in anyone who may have additional insights in two areas.

Information on the early targeted marketing of Tampax specifically to sunbathers.

Information on any specifically targeted marketing materials to nudists, naturists, or free beachgoers.

Additionally, thanks are due to Brian Curragh, Historian and Archivist with British Naturism, for assisting in the research for this article.

Thank you.

Thanks for the feedback. I do hope that this article does engage others into a discussion that explores not only the topic of female cycles, but how most commercial products are not marketed specifically to the small population of nudists. In 1938, women were wearing long dresses, block heels, hats, and regularly had bulky pads strapped between their legs, all of which greatly hobbled their capacity for recreation and movement. I would think that a product like Tampax would be a quantum leap in liberating women, not unlike the impact of the birth control pill in the 1960s.

Dr. Pollen, Thank you for your comments. While Edward Carpenter in the UK and Bernarr Macfadden in the USA were promoting more physical activities and less restrictive clothing for greater movement c1900, there was no open discussion of menstrual pain or how to better address the discharge. While sponges had been used, I have not seen ads for them. This topic was just not openly discussed, let alone written about. The menstrual cup was patented about the same time as the Tampax tampon, and yet it too was not marketed in the materials targeted to those who might be physical active and / or want to be without clothing. I have been working my way through a number of Havelock Ellis books and have been surprised at the lack of mention of menstruation. He does write about the equal energy expended by males and females for their different roles, but then assigns a type of "weakness" or need to stay close to the home or "nest" which keeps women from being active in public life. These are all factors that make this 1938 Tampax ad so remarkable. It would be great to know if Gertrude Tenderich had experience with nudism in Germany or if someone from the advertising firm was similarly experienced to know to specifically market in Sun Bathing Review. The ad brings forward the topic of menstruation, the potential to deal with it in a way that allows freedom from pads and clothing, and puts it in a positive light of being able to enjoy every hour of sunshine. It is a unique ad in nudist publications from my research.