Pettibone Park affair

How a nude bathing scandal redrew the Minnesota-Wisconsin border—America’s last great state line shuffle

The last significant state border change in America was due to nude bathing. Yes, you got that right: nudity caused the last significant movement of state borders in the United States. In the last few years, you have undoubtedly heard of many real attempts to change state and even Federal borders. Wendover, Utah, wanted to move to West Wendover, Nevada, due to time zone and gambling issues. Parts of Oregon and California have proposed merging with Idaho over liberal and conservative values. Point Roberts, Washington, seems a better fit for Canada, and some areas in Maine and New Hampshire seem better suited to Canada, as some areas in Canada seem to be American. The UP of Michigan and Northern Wisconsin have been bloviating about forming the state of Superior for decades, and Bill Maher on HBO has always thought the two Dakotas should be just a single Dakota. Yet it took nude bathers within eyesight of a large Minnesota town’s park to actually get a border change accomplished. I named this the (Great?) Minnesota/ Wisconsin Border swap because, in reality, it has no name that I am aware of. Even the people it affected apparently forgot about it, as we will note.

Pettibone Park: a gift with strings attached

The whole ordeal started simply enough. Pettibone Park on Barron Island, just across the La Crosse Wagon Bridge, was established as a gift to the city of La Crosse in 1901 by the former mayor of that city. Barron Island was then a rugged island that formerly housed the original settlement of the area. It had even been the site of a proposed city, which did not get off the ground. Later, because of unpaid taxes, the land was seized by Houston County (MN), of which the island was part at that point. The land was purchased by former three-term mayor Albert Pettibone and a lumber baron in 1901 for $62,000 from D. J. Cameron. He and his wife, Cordelia, intended to construct a park there for public use.

Understanding that the park would need operating funds and not wanting to burden the city budget, Pettibone gifted the park project to the city of La Crosse along with $50,000 to maintain it, with the stipulation that the city would own the park. It all seemed so simple and civic-minded. Pettibone was considered a philanthropist and received accolades. Despite the park initially being operated as a foundation, the stipulation was for the city to own it, and that was where this happy story took an unexpected nearly two-decade turn.

You see, there was one small issue with all these stipulations. Under state law in Wisconsin (Wisconsin had a variety of laws that seemed like good ideas at the time until they were not), La Crosse (or any city for that matter) could not own property in another state. The fact that the city had built and maintained the roads on the island was moot (they could not own them either). The toll on the Wagon Bridge had caused so much anger that Houston County, Minnesota that they rarely even replied to calls to maintain their part of the road on the Minnesota side.

La Crosse put their foot down. If they could not own it, they were not going to maintain it. Eventually, people also worried that public safety could be at risk since the nearest deputy was probably 20 miles away in Caledonia. In that era, it would take a day or two to arrive. Trying to get the two states and then the US Congress to solve the issue was not as simple as one would think. It seems Houston County was no fan of La Crosse.

Islands of conflict and compromise

In an effort to convince Minnesota to cede the island outright to Wisconsin, a committee of five residents was appointed by the La Crosse City Council to appear before the Minnesota Legislature and plead their case. Houston County was having none of this. The Minnesota Legislature easily defeated the measure. MN Representative Putnam came up with a better idea after the bill was defeated in 1903.

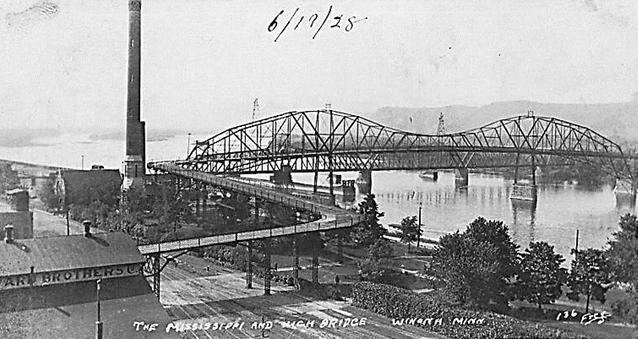

It seemed that Red Wing had a channel island that caused that city much consternation. Island 24, just across from their new High Bridge, was little more than a large sand bar in places, but it was a hotbed of illicit gin distillation, prostitution, and all sorts of nefarious activity of which Pierce County, Wisconsin, seemed to care little to enforce. It was even considered a dangerous undertaking for a farmer to drive on the road back from Red Wing after dark due to the lawlessness of the road through the island. Thus began the push for the interstate land swap.

The issue was brought up again in 1905 in the Minnesota Legislature, with Red Wing and La Crosse now proposing swapping islands for building amusement parks, but nothing was done about it. After a period that resembled more of a ground war across the river in Red Wing, in 1913, the issue was brought up again in the state of Minnesota legislature. In Minnesota, the objections of Houston County were not considered relevant as the den of iniquity had to be stopped in Red Wing, and the bill was easily passed pending approval in Madison, which was never considered a problem….until it was. Wisconsin demurred this case until 1915. Shockingly, it was rejected by a simple five to two vote in committee with no debate. The lawlessness of Pierce County must have had powerful friends in Madison.

It is tough to appreciate how corrupt Wisconsin was in that extended period in the beginning half of the twentieth century until you start to think that many of the hideouts of the notorious gangsters of the Twenties and Thirties were located in the “Badger State.” Those stories are beyond this one. It was then that Winona came to La Crosse’s rescue in 1917.

Winona’s bathing beach

It is not clear which city came up with the new idea of offering Minnesota the smaller and less significant Latsch Island in exchange for the 320-acre Barron Island. Latsch Island or Island 72 as it was officially called back then, was a small 48-acre island lying similarly in Winona as Island 24 was at Red Wing. Like Island 24, this was basically a treeless island whose ownership at the time was somewhat conflicted in the historical record, especially since the island was growing naturally to the south through sand deposition. The best source indicated that at the time, the island was owned by the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad Company, or at least most of it.

Unlike Red Wing’s lawlessness, Winona had a drowning problem at various unsupervised swimming points around the city. Way too many residents could not resist the urge to swim in the river and often chose the wrong time or place by putting their lives at risk. Many died. Having a public beach was considered a plan to promote public safety and personal hygiene. Rarely has there been a city-wide mayoral campaign that seemed only built around public bathing.

When John A. Latsch, a Winona businessman, became mayor in 1906, he negotiated an agreement with the railroad to lease the island to the city perpetually for use as a bathing beach for $10 per year. The island was already connected by the unique Winona Wagon Bridge and was willing to rescind any toll for people going to the beach.

The railroad was not very receptive to this idea initially. They did not see the civic issue or have much concern over a few naked “urchins” swimming on their island, as they called them. They also did not want a city waterpark on their property. Latsch and his connected constituency, some of who shipped on the railroad, did not take the CNW’s reticence lightly and did not ask the railroad without a plan B. A number of Winona’s wealthy — valued freight customers all — later entrained (we may assume aboard a C&NW coach) to boycott shipping on the railroad systemwide. The railroad soon changed its mind.

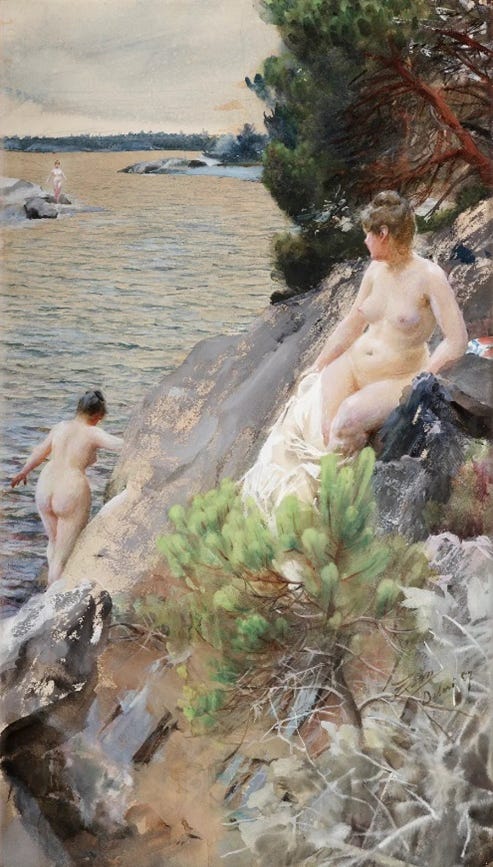

Island 72 was chosen since that place had been a swimming place for years, albeit usually sans clothing. Having been settled by recent immigrants from Scandinavia and northern Europe, these people were used to bathing naked, and many Scandinavians to this day think wearing a swimsuit, especially a wet one, is unhealthy. The Finnish naked sauna culture had already caused concern in many conservative Minnesota communities. With the completion of the bridge a decade earlier, this habit converted mostly to an after-dark activity due to privacy concerns. To solve the problem, the wealthy Mayor Latsch promised to donate $10,000 to the city to build a bathhouse to change, plant trees for cover, and for the city to purchase 750 bathing suits for men and boys and 50 for women to rent out to the patrons for a nickel so they would be encouraged to cover up since few residents owned swimsuits.

A bathhouse was quickly built, and the John A. Lasch Public Bath opened in 1907. Sand was dredged from the main channel of the river and used to expand the beaches and contour the river bottom at the bathhouse site. Piles were driven deep into the island for a foundation. Steel rails were bolted to the top of the pilings, solidly anchoring the 210-foot-by-23-foot bathhouse to the beach. When completed, the bathhouse had lockers for 116 patrons. There were two general dressing rooms, one for men, one for the ladies, with the ladies located on the west end of the building “so that they will not have to walk so far.”

Sunbathers save the day

The bath was a great thing. Public sanitation was improved citywide, and drownings decreased. During the summer some people even bathed twice a day since many did not have a way to bathe otherwise than to do it in the river. There was still one (major?) problem, however: not everyone wanted to pay a nickel to rent a bathing suit. Some of the men were also drunk, and if what was called lewd or otherwise illegal behavior happened, the city of Winona had no jurisdiction to arrest anyone on the island. Brave naked people even waived at the passing trains. Whereas La Crosse’s jurisdictional crime problem at the Pettibone Park was theoretical since no crimes had occurred there in fifteen years. In Winona’s eyes, their crime was ongoing on hot weekends. By the time word made its way to a constable in Wisconsin that someone was swimming without a bathing suit, it might take hours, if not days, for anyone to investigate, if at all.

As such, Winona became much more interested in La Crosse’s border problem, and in 1917, Minnesota passed a law agreeing to this new land trade on March 26. As apparently the skinny-dipping lobby was less connected than the bootlegger and speakeasy lobby in Madison. The bill there was brought up without discussion that April, but this time, the vote was almost unanimous.

Winona was so concerned that the trade looked on paper that Minnesota would be getting the short end of the deal (in both land value and tax income), the mayor of Winona sent a letter supporting the bill to the US Congress cryptically referred to their clothing-related bathing problem. With this letter, and since the two states had now agreed to trade islands, the US Congress took up the matter, and it zoomed through committee. The redrawing of the border was officially approved without much-added trouble by both houses of the US Congress and signed by President Woodrow Wilson in September 1918. It took 15 years and nearly a war at Red Wing, but in the end, it could be said that nude bathing led to the only modern change in the region’s state borders.

In 1923, due to declining water quality, they moved the entire bathhouse to the other side of the island to be on the main channel. For reasons unknown, neither the state, nor Winona County assigned this island to any township or municipality upon its inclusion within the state of Minnesota, despite now being in Minnesota, it was in all actuality, nowhere. It may have never even been in Winona County. As such, the railroad had not been assessed any taxes as the land was not part of any tax district. Had anyone ever been arrested for public indecency or any other crime not explicitly covered by state law from 1919 through 1939 by city or county policeman in Winona, a smart lawyer could have had the crimes thrown out on procedural issues.

This was noticed in 1935 when a relative of the Landrieu family, the famous Louisiana political dynasty, was killed along with his wife when they hit the La Crosse Wagon Bridge with their car; the span collapsed, and the Plymouth went into the river.

Minnesota was eager to share the costs of the repair and the replacement of the bridge until someone in St. Paul realized they did not own half of the bridge anymore, and no one had ever transferred any of the deeds for the two islands. In fact, they had been taking care of the road, too. La Crosse and Wisconsin had to pay the entire bill. Likewise, a decade later, Minnesota had to replace the Winona bridge but somehow convinced Wisconsin to also pay a little. When the bills were all totaled up, Minnesota still paid a lot more and is still paying more, mostly due to the bridge(s) in Wisconsin lasting longer. Today, Wisconsin is about 272 acres bigger than it once was, and Minnesota is smaller.

Pettibone Park is still a well-used park today. The Winona’s bathing beach closed in 1972. Locals note that hardly anyone swims in the river anymore. Nude use on the river… occasionally, one comes across a few brave people in a corner of the river. 🪐

Olaf, Great article. Now we can add that nudists have helped change the laws of the nation on gender equality, use of the postal service, what can be worn, and how state lines have been determined. Thank you for this insightful article.

Quite a little history lesson. Lots of back and forth involved.