Dolls and Dues, Suburban Wife, The Torrid Teens, Call Me Bad, Dial ‘M’ for Man—all characteristic titles for pulp fiction short stories and novels of the 40s and 50s. But Orrie Hitt (1916-1975) was not your typical writer of pulp fiction, and some of his 150-plus novels also have more unexpected and intriguing titles—take Panda Bear Passion, Love in the Arctic, Ex-Virgin, Diploma Dolls, and Abnormal Norma for example. The writer Brian Greene dubs Hitt “the Shakespeare of Shabby Street,” and a “visionary artist” who explored characters within “moving human dramas.” (Shabby Street is both a metaphor here and the title of an early Hitt novel.)

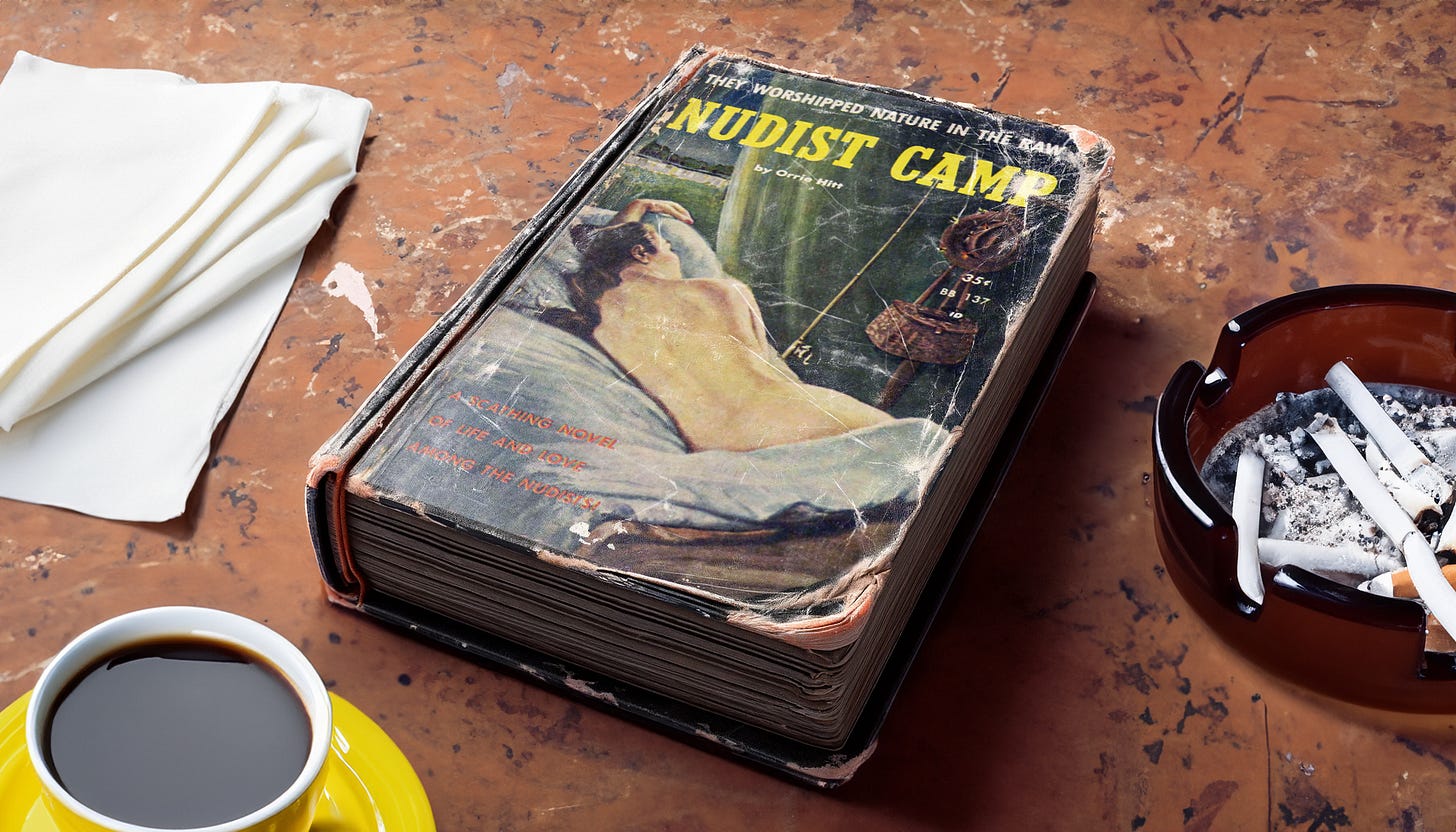

At first glance, Nudist Camp, published in 1957, appears to be just another exploitative example of the genre, but there is a little more going on between its covers than meets the eye.

Pulp with plot

Strictly, the literary term “pulp” refers to fiction magazines, published between the early twentieth century and the 1960s, printed on cheap, acidic wood-pulp paper. Like the short stories of the magazines, pulp-fiction novels boasted lurid themes and equally lurid (now highly collectable) covers. Often writing under a variety of different names, pulp authors of the 1950s might well be producing a 40-50,000-word novel a week. (On a personal note, in the early 1980s when I first taught in the Department of English at San Diego State University, I knew a graduate student who was supporting himself by writing erotic novels for a local publisher and, like those1950s authors, producing four books a month.)

The cover of Nudist Camp is not particularly lurid at all, the anonymous illustrator clearly paying homage to a familiar trope of art history; however, regarding the cover’s accompanying text, as with most pulp fiction covers, it promises more than it delivers. The nudist camp is, in fact, no more than a plot device, yet when Hitt describes the club and its inhabitants, it is without judgment – indeed, it is with respect: “You know,” observes one character, “some of the finest folks in the country are nudists.” And Hitt clearly has some knowledge of the history of social nudism, as when the “leader” of the “camp” gives a speech to the campers that could be drawn straight from William Welby’s 1935 volume The Naked Truth about Nudism. The text on the cover of Nudist Camp promises us that this a “scathing” novel about life among the nudists. I seem to have missed the Scathing Chapter. One wonders whether the judgment-loaded “scathing” is there to protect the backside of the publisher from would-be censors.

A nudist protagonist

Della, Hitt’s protagonist (unusually, for the time, a strong woman), is Icelandic, and not simply “exotic” for being so; as Hitt presents Della, her cultural upbringing allows her to be comfortable—and confident—in her own skin. People keep saying to Della, “You must be used to social nudity, coming as you do from Iceland.” (It’s funny: I don’t believe that anybody has ever said to me, “Oh, you must be used to social nudity, coming as you do from England.”) Hitt makes the point clear that his protagonist is from somewhere other than Puritan-founded America: from Iceland which has hot springs, just as Scandinavia has saunas, and the rest of free-spirited Europe has the Mediterranean and Northerners who appear to be oblivious to cold temperatures and heavy rain. At one point in his life, Orrie Hitt was the manager of an airport club in Iceland, so he and his family were probably throwing off their clothes and jumping into one of those hot springs as soon as he closed down the lounge for the evening.

Della is a strong female character; however, she is also the victim of domestic abuse at the hands of two men, and, improbably, returns at the end of novel to the arms of her physically violent ex-husband. While Shakespeare may have occasionally relished the improbable, at times the reader has to work a little too hard with this novel. As the book screeches to a halt, one has the sense that Hitt is hurrying toward a deadline. He probably is. Similarly, while the author clearly knows something of the laws against nudity in New Jersey as compared to New York, the densely populated, tented nudist camp is established more or less overnight. But, then, when nudists put their minds to something . . .

As I’ve noted, the novel’s focus is not the nudist camp itself; rather, it is a blackmailing plot that abuses members of the camp—involving blackmailers who are, at heart, non-nudists.

In the end…

Hitt does demonstrate respect to his nudists, and there is talk of body positivity – not bad for 1957 pulp fiction. However, there is also a much less admirable passage early in the book: “Ricky’s sister was a tall girl with a thin face and an unimportant body. Her one claim to beauty was a dimple in the middle of her chin.” This is not a character speaking. That “unimportant”—and its erasure of the sister’s personhood—is inexcusable. It’s horrific, and I debated whether I should continue reading. Does a mistake define a person (or a novel)? There is much in this novel that is of its time, but Nudist Camp also has its more pleasant surprises.

“‘There’s something to this nudist thing,’ Della said.” I agree. There is something to worshipping nature in the raw.

Indeed there is. 🪐

An amazing review! I love the layers of your analysis, from the pulp fiction genre, to the character development, to how the book treats nudism in the context of the era it was written, to the "Shakespeare of Shabby Street" author himself, including speculation as to how he might have acquired an appreciation for social nudism. On this cold and wet wintry day, it makes me want to curl up by the fire and read some juicy nudist-themed pulp fiction.