More puritanical panic over nude art

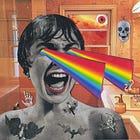

A rebuttal to The Federalist’s fearmongering and the false conflation of art and pornography

In a recent piece for The Federalist (“Art Shouldn’t Get A Free Nudity Pass Just Because It’s Art”), writer Meg Marie Johnson tries to revive a tired impulse: the idea that nudity in art is somehow a moral threat. Cloaked in literary references and appeals to religious virtue, her argument is a familiar one. It plays to a long American tradition of puritanical discomfort with the human body — one that not only misreads history but flattens centuries of art and culture into a paranoid morality play.

It’s worth noting that The Federalist isn’t just any old blog. It plays an active role in shaping a broader conservative narrative that often casts openness about the human body as a cultural threat. Johnson’s essays, presented as earnest concerns, are part of that larger project: to recast art itself as a kind of gateway drug to moral decay.

At the heart of her argument is a wildly selective view of history. She leans heavily on the supposed moral depravity of ancient Greece and Rome, suggesting that because those cultures had their flaws (and they did), their art — especially nude art — must be suspect too. In a very similar essay from last year for Public Square Magazine titled “Rethinking Nudity in Art,” Johnson laid out many of the same claims, insisting that classical nude sculptures were never truly “innocent” and that the distinction between art and exploitation has been dangerously overstated.

This is a misreading so basic it almost feels disingenuous. Greek sculptors didn’t carve nude figures because they wanted to titillate; they did it to represent ideals — strength, divinity, excellence. Nudity wasn’t about cheap thrills. It was about embodying humanity’s highest aspirations. And far from rejecting this tradition, Christian Europe embraced it, built on it, and integrated it into some of its most celebrated religious renaissance art. Are we supposed to believe that Michelangelo’s David or the Sistine Chapel is really just ancient Greek depravity repackaged? That’s the absurd conclusion Johnson’s logic leads to.

A big part of Johnson’s case leans on Leo Tolstoy’s later writings, where he grew suspicious of sensuality and beauty in art. It’s true that Tolstoy was skeptical, even hostile, toward a lot of what he saw as indulgent or elitist art. But wielding Tolstoy here as some kind of absolute authority is shaky at best. His later views, shaped by a personal crisis, were rather extreme, and if we really followed them to the letter, we’d have to throw out not just nude sculpture but most of Western canon from Shakespeare to Beethoven. Citing him here feels less like a thoughtful appeal to history and more like a poor attempt to sound erudite.

Johnson also tries to collapse the distinction between fine art and pornography — though she does distinguish them, incredibly, by saying that art “isn’t addictive” like porn is.

The problem isn’t with porn, and it isn’t with art. Many have tried to articulate the objective difference between the two, and most fall short; however, our society seems to have agreed that there is a definable difference, even if it is that you’ll “know it when you see it.” By and large, the generally accepted definition is usually that porn exists primarily to arouse; art explores vulnerability, mortality, divinity, beauty. But does that mean porn can’t explore those themes? One could argue that it inherently does. The fact is, porn is far more readily censored in our society, while art tends to benefit from wider cultural and legal acceptance. Both deserve freedom from censorship, but most agree they aren’t the same — and flattening them into one category is just another way to justify broad censorship and control.

What Johnson is really tapping into is a familiar American tradition: the moral panic. We’ve seen it before — with the Comstock laws banning “obscene” materials, with censorship campaigns against classic literature, with attempts to scrub textbooks of anything that challenges a narrow view of virtue. Always, the rallying cry is the same: Protect the public. Preserve morality. But the effect is always the same too: suppress bodies, suppress stories, suppress art.

One of her more revealing moves is comparing the sight of the naked human form to “exposing sacred temple rituals” — framing nudity itself as sacrilegious. But if the body is sacred, as so many religious traditions claim, then treating it with reverence should mean not hiding it in shame, but understanding it as a source of dignity and wonder. Early Christians rejected the idea that the body was corrupt or evil; they celebrated the incarnation — the idea that God took on flesh — as the ultimate affirmation of the body’s goodness.

Johnson’s argument isn’t a call for deeper reflection about art. It’s a call for a smaller, more fearful world — one where the sight of a nude figure is automatically a threat rather than an invitation to see humanity more clearly. Nudity in art doesn’t degrade human dignity. Fear of the human form does. 🪐

I love this article so much... but I will argue that art IS addictive.

Back in the late 80s, while servine in the Marine Corps, I spent an entire day in the L.A. County Art Museum.

I wandered from frame to frame, looking for that next "jolt". I needed the next piece to make me pause, make me think, make me wonder.

I have heard the phrase "chasing the dragon" used, historically, about opium use.

My dragon was that next photo, that next sculpture, than next painting that drove some part of my mind over the edge into an oblivion of bliss.

It still is.

This is truly excellent writing, Evan. I so appreciate your measured response in the wake of absolute tomfoolery!

The part of this that I simply can’t understand is the basic premise that humans are attracted to (sometimes aroused by) one another, clothed or not. That perpetuates the human race.

So how then do we contextualize the long standing appreciation for the beauty of the human form, and why are we so hung up on sculpture (where the subjects are typically not well hung! 🙄)

Regardless, you present a compelling case that calls out the author for their predisposition to demonize at will. Really? The Romans and the Greeks??!! Get over it!

Thanks for this thought provoking piece.