Africa: The continuing tradition

A journey through Africa’s naked heritage and artistic expression

Africa. Birthplace of all mankind. Naked we came from there. Naked its people remained. Naked in the face of Muslim armies. Naked in the face of Christian missionaries. Naked in the face of modern consumer society. Though their numbers dwindle, countless Africans remain true to their naked heritage. And her sons and daughters, no matter how many centuries they have been away, cherish the tradition of body freedom. Slave-owners could not beat it out of them. Preachers turned some of their heads around, but not all. They still flaunt it. More and more people are finding the pride in themselves that is Africa.

So it was, and so it is.

Art of Benin

Between 1550 and 1650, Nigerian artists in the kingdom of Benin crafted more than a thousand bronze plaques and nailed them to the pillars of the palace. Though they used the same lost-wax casting method as the ancient Greeks and Renaissance Europeans, the Benin artists refined the technique to produce the most delicately thin bronzes the world has ever seen. High-relief human figures stand against a background of low-relief floral designs. The bronze plates mostly record the Oba, or king, in his royal kilt, and soldiers in their skimpy uniforms. One plaque shows three court attendants in the undress of the common people. Their hair in long braids, wearing beaded necklaces and bangles, these men would certainly not have wanted clothes to cover any of their elaborate tattooing. More about body decoration later.

In 1668, a Dutch traveler became the first and only outsider to view the plaques in place. By the time the next Dutchman arrived, they had been taken down, crated into large wooden trunks, and hauled farther inland for safety. For the next two hundred years, they served as a bulky card file on court etiquette to be consulted whenever a question came up concerning the proper dress or undress of a certain-rank official for a certain occasion. Centuries passed. Portuguese traders had come and gone; Dutch traders had come and gone. But when an English trade delegation died in an ambush in 1897, the British invaded the country, took over the government, discovered the trunks filled with artworks, and sent most of them off to museums around the world. (Notice they did not send the "indecent" one seen here.)

Yoruba traditions

Just west of the Benin people, the Yoruba tribe had been raided heavily during the days of transatlantic slavery. Large Yoruba concentrations have kept their religion alive in Brazil, Haiti, and Cuba, where it flourishes under the name of Santeria. To understand the religion, it is necessary to know something of the African concept of time. Time is divided into three periods: present, remembered past, and distant past. When you die, you move from the present into the remembered past. When your last acquaintance dies, you move into the distant past. The future is not yet time; it is only potential time. When Christian missionaries saw Africans conversing under a shade tree at midday, they grumbled that those lazy people were wasting time. How little the missionaries understood. Those people were not wasting time; they were creating time—taking something which did not exist a few minutes earlier, and turning it into a lasting memory.

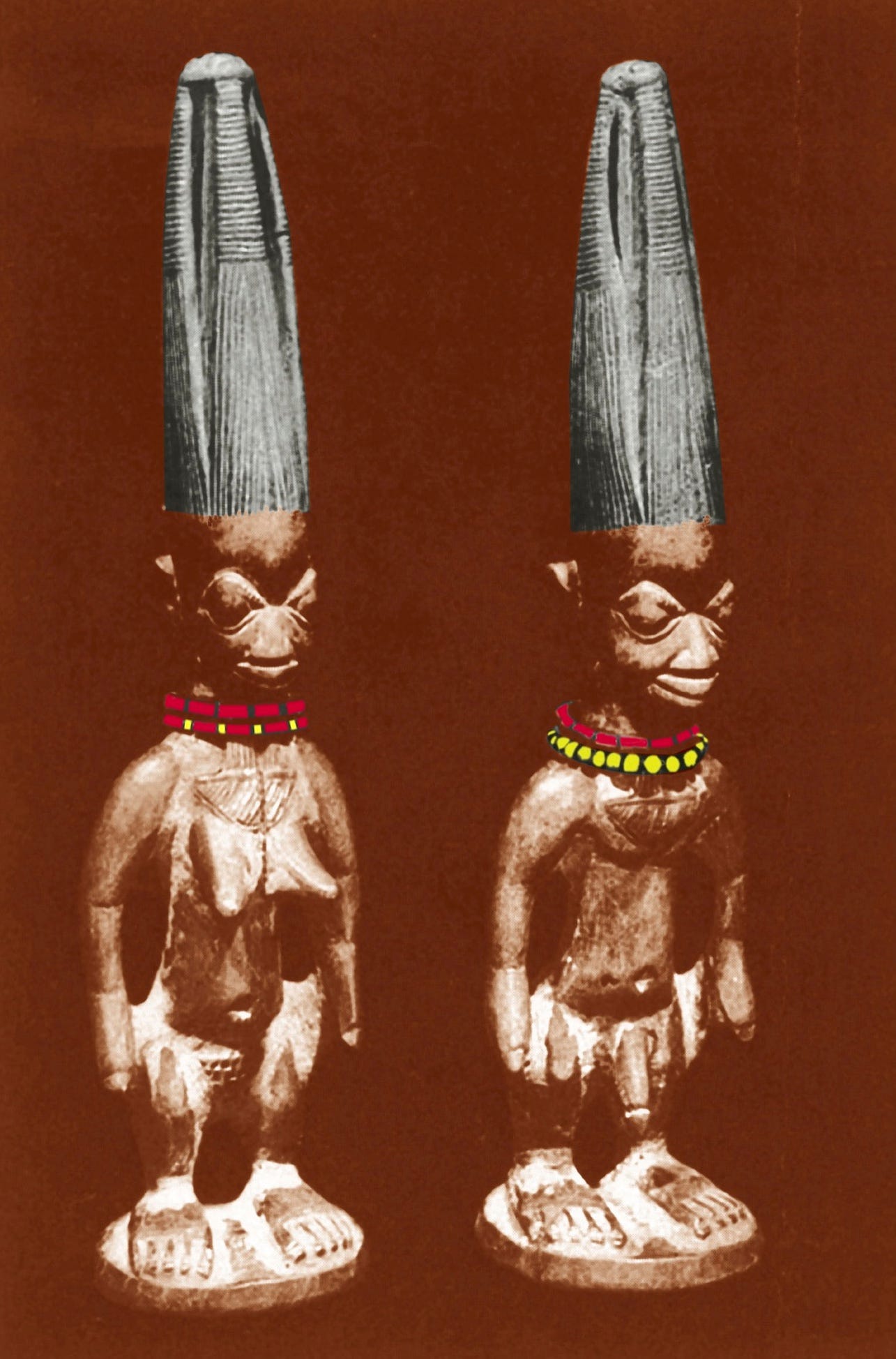

Many African religions teach that God was once closer to mankind, but because of abuse, has become more distant. One of the more colorful versions says that people took bites out of the clouds when they felt hungry, and wiped their greasy fingers on them; so God climbed a spider web up to a higher heaven. With direct communication cut off, messengers now become necessary. And who better for a messenger than friends and relatives in the remembered past? These people now dwell both in the world of the spirits and in the memories of people here on earth. But how to attract these spirits to hang around, nearby, ready to carry a message whenever needed? Just as people put out birdhouses, the Yoruba put out carved wooden totems—human figures that can serve as houses for the spirits of the remembered dead. (These have nothing to do with American Indian totem poles.) To look as inviting as possible, the totems always have the most desirable physical attributes: firm pointed breasts on the female figures, and large penises on the male figures. Among the Yoruba, the bond between twins is a powerful one. If one twin dies, it becomes an especially potent messenger. Thus, a favorite form of totem among the Yoruba are the ibeji, or twin figures. The ibeji traditionally appear as one male and one female, regardless of the sex of any actual twins.

Protestant missionaries have generally felt it their first moral duty to "clothe the naked." Conversion to Christianity could wait. In their eyes, nudity, polygamy, and idolatry formed a trinity of horrors to be exterminated at all cost. They failed to realize that the totems which they urged people to burn represented neither gods nor objects of worship. Catholic missionaries have been more subtle in accommodating traditional art forms into a new religion. A fine example of this policy is the famous Missa Luba, the Catholic Mass set to Congolese music. Yoruba ibeji totems now sometimes appear as clothed statues of Jesus and Mary, to be carried in church processions. Another hybrid presents the ibeji as two nude angels. While the female wears the horns of traditional spring planting ceremonies, the male figure is especially interesting. Here the messenger between man and God is conceived as something like an official government messenger, wearing only his symbols of authority: pith helmet, wrist watch, and dispatch pouch on a belt.

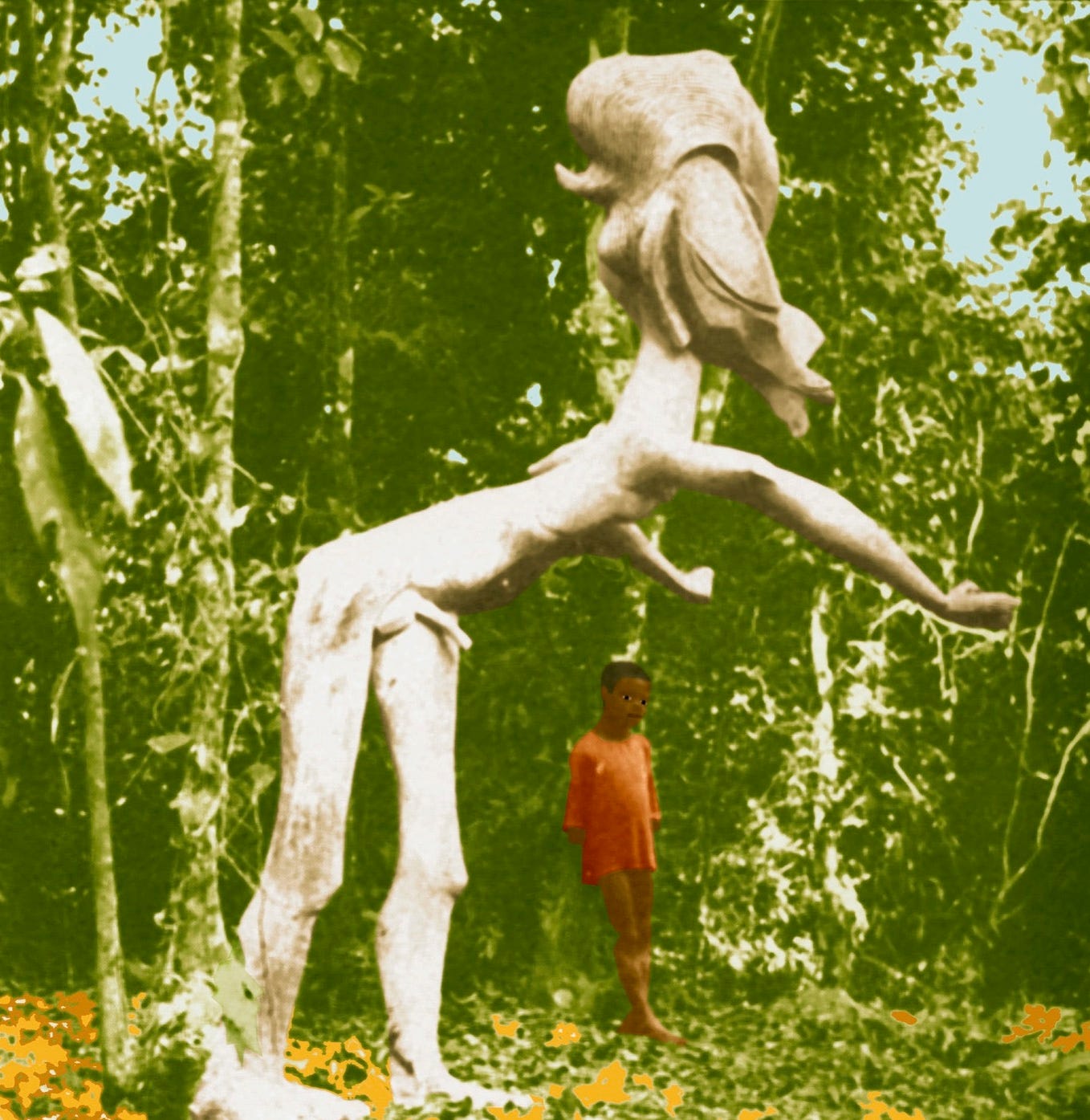

But white-robed Islam arrived in Nigeria well before Christianity, and still poses a stronger threat to Yoruba religion. The Yorubas recognize over 600 godlings, called orishas. (Only about 20 of them are remembered among Santeria worshipers in the Americas.) Some of the orishas are strictly local, but even the best known have their center of worship at a particular place—just as Athena presided as patron goddess of Athens, or Delphi held the main temple of Apollo. The great mother goddess Oshun is particularly associated with the River Oshun as it passes through the city of Oshogbo. There, a surprising revival of Yoruba religion has been going on since the early 1960s, inspired by the architecture and sculpture of an Austrian woman, Suzanne Wenger. She could find only Muslim bricklayers to assist her, but they soon entered into the ancestral spirit. More fanatic Muslims destroyed the first of these new temples.

Among Wenger's Islamic assistants, Adebisi Akanji has created remarkable walls of (clothed) cement human figures—both for the Yoruba temples and to screen off the Esso gas station. (Some of Africa's most exciting architecture finds expression in its gas stations. The Total station in Nairobi is another one not to be missed. Nothing needs to be ugly.) Alajere, god of fire, change, and unpredictability, had been all but forgotten at Oshogbo until Wenger rebuilt his shrine. Now a nude flame-haired statue of Alajere rises above the cliff overlooking the river, doing an ecstatic dance of welcome (at a respectful distance) for his opposite, Oshun, great goddess of childbirth and water. On another level, this cosmic attraction of opposites can symbolize the marriage of artistic inspiration and the spirit of traditional Yoruba religion in Wenger's own work.

The Nuba people

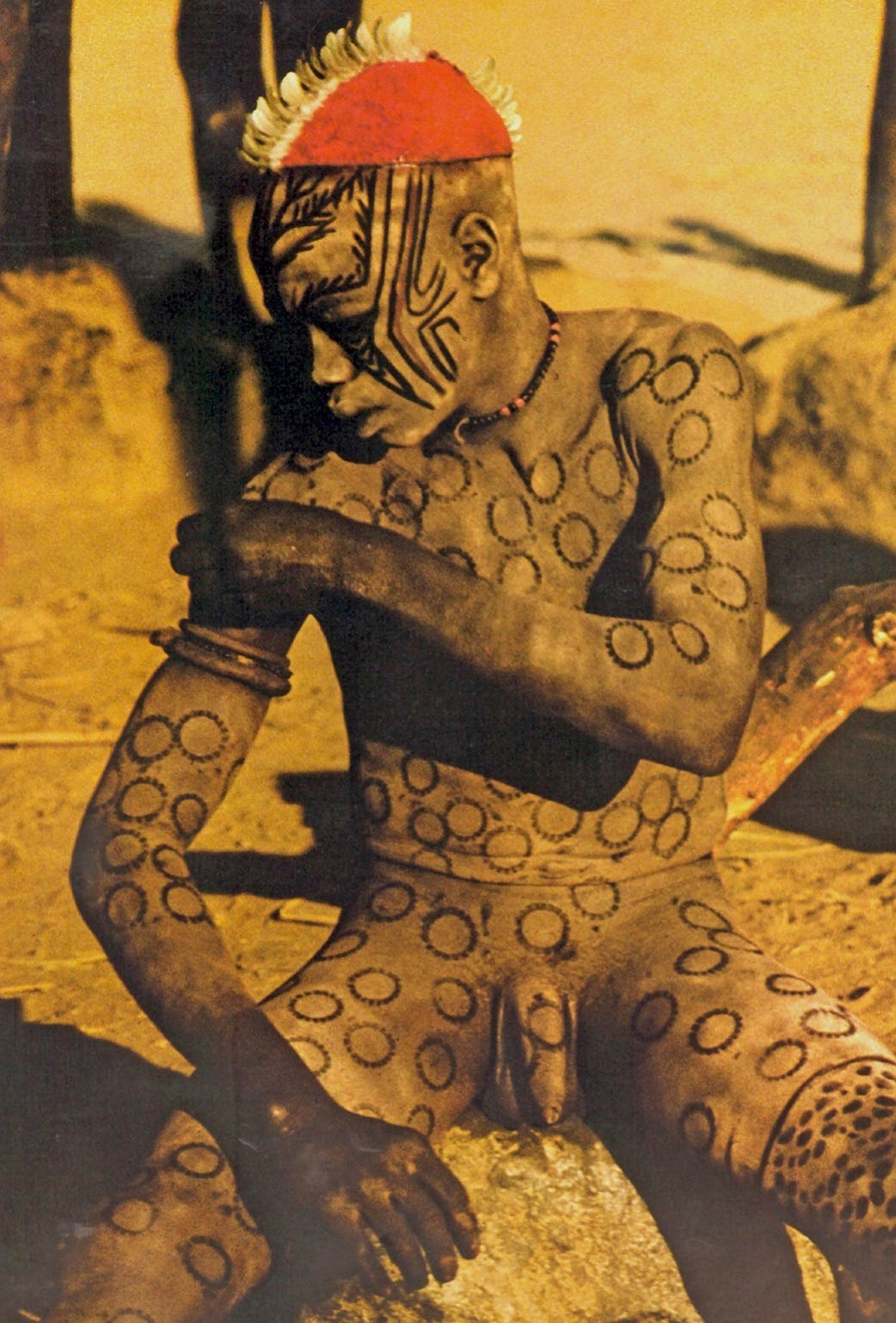

It may be well enough to put up statues of nude gods in city parks, but you will hardly find nude people walking the streets there. For that, you must go deep into the jungle, or clear across the continent. The largest concentration of Africans living traditionally nude recently dwelt in the rocky deserts of southern Sudan. German photographer Leni Riefenstahl visited the Nuba several times. She found village after village where no one ever wore clothes until approaching middle age. Keeping the body beautiful mattered above all. And that beauty was there as an inspiration for everyone to see. The Nuba used clothing almost as a social punishment inflicted at the first sign of letting the body turn to flab. Again, beauty was the guide: best to cover up an eyesore.

Art among the Nuba took the form of body painting. When Riefenstahl showed an interest in this art, the young men began changing their decorations several times a day. The astonishing array of designs at their command meant that the photographer sometimes failed to recognize a man she had spoken to just a few hours before.

Then thirty years of civil war engulfed Sudan, as the Islamic government of the north tried to starve the Christians and the native people of the south into becoming "civilized." For a long time, no one knew whether the Nuba were dead or alive. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, Riefenstahl returned to the Nuba villages—only to find that the people had all converted to Islam and now felt embarrassed to see pictures of themselves living freely as they had for thousands of years.

Cicatrization of Surinam

Rather than body paint, traditional Nuba women preferred the permanent designs of cicatrization, or scar patterns from hundreds of little slits cut into the skin. This cosmetic surgery occurs soon after the breasts form, and was once common all across Africa. For instance, the similarly-decorated “Bush Negroes” or Maroons of Surinam originally came from Nigeria and nearby areas. On reaching shore, they soon escaped from slavery and set up their own African villages in the South American jungle. There the tradition of bare-breastedness and cicatrization continues. Yet it remains a tradition of constant change. An interesting study of cicatrization patterns in Surinam shows that fashions in body decoration change just as rapidly as fashions in clothing do. The trend in recent decades has been toward smaller areas of scar patterns, but the fashion pendulum could swing as unpredictably in this as it does in clothing.

The call of Africa

Unpleasant though the subject remains, one point needs to be made about the transatlantic slave trade. Some West African prisoners had never worn a stitch in their lives; others came from puritanical Muslim areas. Shipboard sanitation remained crude under the best of conditions, and was so appalling below decks on the slave ships that a great many died in the filth and disease. It did not take slave traders long to notice that the nude prisoners, without germ-infested clothing, arrived in healthier condition. Soon all Africans were routinely stripped before boarding ship. They all made the crossing nude, regardless of previous background. For most of them, their first puzzling experience with clothing—(Where do the arms and legs go?)—came just minutes before they stepped onto the auction block. Clothing and slavery came together. Early slave-owners grumbled that new slaves kept giving away their clothes, despite heavy penalties for this display of ingratitude.

Several European and American sculptors from the sixteenth through nineteenth centuries caught the symbolism of clothing and slavery. Statues cast off their clothing along with the expectations of an oppressive society. Now, more than a century later, isn't it time for people to do the same?

The spirit of Africa calls. 🪐

Editor’s note: This article was previously published and is available in Paul LeValley’s book, “Art Follows Nature: A Worldwide History of the Nude.”

Paul LeValley is an author and researcher with a deep interest in naturism and art history. He has written four books on naturism, including “Art Follows Nature,” “Seekers of the Naked Truth,” “Naturist Writings of Paul LeValley,” and “In His Own Image Created He Them: Nude Illustrations of the Bible.” He currently serves as the president of the American Nudist Research Library in Kissimmee, Florida.

You can learn more about and purchase Paul’s books through his website, here.

Terrific information! Thank you for sharing this here, Paul!

Thank you for this interesting article and references to the books. I look forward to reading more.