The nudists of Sager's Lake

A historical tour of the conflicts and controversies that formed the resilient, 90-year-old Lake O’ The Woods Club

“Welcome all ye who seek sunshine and rest, for here they are abundant.”

Prologue: A fleeting retreat

Relentless rain became the uninvited guest at our weekend family reunion, but the joy of reconnecting after so long was unshaken. Nothing could deter my wife's family from reveling in the long-awaited union, finally introducing our four year old son, Eli, to his extended family in the southern Chicago suburb where my wife herself was born.

While rain did not hinder our jubilations, it did pose a dilemma for my Monday morning scheme. From the moment Kim and I conceived of our visit to see her Chicago family, I secretly hoped for a nudist mini-retreat, endeavoring to check one specific nudist club visit off my personal bucket list.

From old photos in antique nudist magazines I had seen of the historic Lake O' The Woods Club in Valparaiso, Indiana, I anticipated a scenic experience. I recently learned that the club was celebrating its ninetieth anniversary this summer—making it one of the three oldest nudist clubs in the country—and for that reason alone I really wanted to see it in real life.

Sadly, for a visit to occur on this particular trip felt like a distant dream. The timing was tight, and our visit really was meant to be a family gathering, not a nudist retreat. I had nearly dismissed it.

Then, like a whisper of fate, a message randomly arrived from a fan of my nudist history podcast, Naked Age, suggesting I look into Lake O’ The Woods Club for a future episode, and urging me to try to meet a man there named Bill P.

Intriguingly, the writer had no way of knowing how close I actually was to the club at that moment, nor that I already had their website up on a browser tab on my phone. I’m not generally superstitious, but I like to take note when coincidence or kismet show face.

Despite the forecast's lingering uncertainty, Monday dawned with a hopeful sky.

With only a few hours to spare, Kim, Eli and I embarked on the hourlong drive from Tinley Park to Valparaiso. We saw only light rain and a lingering sense of a storm receding. As we neared the entrance of this historic oasis, the clouds actually parted.

We pulled up to the front gate and pressed a little “call” button.

“Lake O’ The Woods club, can I help you?”

We spilled out of our rental Kia into the asphalt parking lot and stood agog as we laid eyes on the picturesque view of a placid, lily dappled lake, enclosed by a perimeter of lush woods. The scene was framed by a cozy clubhouse on one side, a children’s playground and diving dock on the other, and underlined by a small sandy beach littered with paddle boats and canoes, adjoining a grassy lawn covered in sunbathing chairs and a volleyball net.

Two plastic decoy swans sat motionless in the water, clumped together; one was overturned, but its effectiveness as a deterrent was undiminished, for nary a goose was to be seen and the grass was conspicuously free of droppings.

I looked up to see an eagle floating furtively over the trees, keeping an eye on things. We jumped when a train horn blared behind us, echoing damply off the trees from the railroad abutting one side of the camp.

Sager’s Lake—I knew it was called from the club’s website—was clear and reflected the now-blue sky, emanating freshness after days of rain. Suddenly the significance of the club’s memorable name was evident—a lake in the woods.

Standing there, taking in this tableau, I felt like we’d entered another era; like we had stepped through time into a 1940s postcard, an idyllic scene of serenity, removed from the hustle of Valparaiso, Chicago, and beyond.

Considering my allotted time slot for a visit fell early on a Monday morning following a weekend of heavy downpour, it was an understandably quiet scene. One woman did water aerobics alone in the swimming pool. Another sat smiling at an outdoor desk in front of the clubhouse. Nobody else appeared to be milling around.

Eager, Eli made a beeline for the playhouse and Kim followed, while I checked us in and paid the gate fee. I’d called ahead, but now I introduced myself and my affiliation with the Western Nudist Research Library, and my affinity for nudist historical research.

I was soon greeted by a friendly couple who looked like they were just about to go on a pantsless hike, wearing nothing between their sneakers and their brightly colored UV-blocking shirts. Both wore smiles. They introduced themselves as Bill P. and Marie.

Before I knew it, my clothes were somewhere other than my body, and we were walking and talking as if we were longtime friends catching up. Marie was kind and affable to Eli, quickly revealing that she is a retired Montessori preschool teacher.

Bill, I learned, is an active resident of the club, a site holder and a member of the board of directors. He’s also passionate about the club’s great history, and gives historical hiking tours along the club’s 1.5 mile Circle Trail, exploring their more than 135 acres.

According to Marie, Bill’s hikes, the length of which took the average person about forty five minutes to walk, often took two hours or more when accounting for Bill’s historical content. The thought of it made me giddy.

I knew that if I started asking questions, we could easily set a new record in the time spent category. Unfortunately, given that my visit was unannounced, and knowing that we only had a couple hours to spare, we sadly had to forego the history hike on this visit. Kim and Eli wouldn’t have had the stamina anyway.

Alas, Bill and Marie kindly urged us to check out Circle Trail at our own pace, and went about their Monday, bidding us a relaxing stay.

I was sad that the historical tour wasn’t in the cards, but still determined to experience this historic club, and resolved to dig into its history and learn more about the origin of this longstanding club on my own time.

With every passing minute we spent there over the next few hours—spotting wild mushrooms along Circle Trail, eating ice creams by the lake side, working with Eli on his kicks in the pool—I fell more in love with this beautiful place. A piece of it came away with me when we left, and since then, I've been captivated by the club's history.

Researching its figures and stories, I discovered the challenges the Lake O’ The Woods Club faced, including police raids, the prying eyes of vice squads, the opportunistic ambitions of politicians, unrelenting media scrutiny, and contentious property disputes.

Histories have been written about the Lake O’ The Woods club once or twice before, usually occasioned by anniversaries like this one—but it’s my hope and belief that this account will dive a little bit deeper into the events, and accomplish a greater perspective of the significance of this incredible and historic nudist club.

The history of Lake O’ The Woods Club

Chapter 1: Sager’s Lake

For more than eighty years before the nudists from Chicago began leasing the land encompassing Sager’s Lake in 1933, the twenty five acre reservoir was essentially treated as a public park, a popular spot for fishing and recreation, especially among students of nearby Valparaiso University. For years, "Sagerology" was a popular euphemism for a party at Sager's Lake.

As early as 1907, the university held events on the south side of the lake,1 eventually establishing the Sager Lake Riding School there as part of its Physical Education department.2 This facility was so integral to student life that the university even constructed a bridge over the railroad tracks to provide easy access.

Affectionately called the "kissing bridge," it became a cultural institution in its own right. Whenever a train would pass, it was customary for students to engage in a kiss until the train had completely crossed.3

In many ways, the story of the nudists of Lake O’ The Woods Club is only a chapter in the larger history of Sager’s Lake, and the many conflicts and controversies which have arisen for generations over the rights to enjoy the lake’s generous bounty.

First called Sager’s Pond, the lake began as a small spring-fed stream, before it was dammed in the early 1840s by William Cheeney for the purposes of establishing a lumber mill.

Cheeney sold his lot to William Sager in 1856, who became the proprietor of the mill. Over the next few generations, Sager and his flour mill established themselves as a key part of the industrial history of the region, selling flour to farmers and townsfolk. He also ran a bakery in Valparaiso. Sager died in 1884 and passed the property on to his ten children, who continued to run the mill and supervise the land and the lake.4

One 1937 article in the local Vidette-Messenger reported:

For years the Sagers have been forced to defend their rights in supervising activities at the lake by legal actions, physical combat and otherwise.

On one occasion they were nearly sent to jail because they became involved in a battle with students who looked upon the lake as a sort of pleasure ground.

In another instance state officials sought to Intervene on the theory that Sager’s lake came under jurisdiction of the state. Suit was filed by the state but later dismissed.5

Interestingly, one of the Sager sons, Chauncey, found another way to derive profit from Sager’s Lake in the 1880s when he began harvesting ice to sell commercially.

He gained some recognition for inventing a technology that automated ice cutting, securing patents in both the U.S. and Canada for his steam-powered ice cutting machine, and was once even featured on the cover of "Scientific American."6

![Engraving showing two Sager Ice Cutting Machines. Source: Scientific American, July 22, 1882 [front page]. Engraving showing two Sager Ice Cutting Machines. Source: Scientific American, July 22, 1882 [front page].](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!8Rsb!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7578fb2b-3cec-42f5-82a8-7b39f30059bb_1600x1302.jpeg)

At some point around 1900, the mill ceased operations, but during World War I, Chauncey installed new machinery7 and reopened the mill to provide flour for farmers from nearby counties. Sadly, after the war ended, much of the market for the mill’s product again dissipated, and the mill was closed for good.

In the following years, Sager's Lake became a crucible of public interest and tension.

In 1922, Chauncey Sager offered to sell the property to the city of Valparaiso, knowing how much the local residents valued the western end of the lake as a de facto city park. The city council declined, opting instead to invest tax dollars in education.

One year later, an unsolicited offer came from the Ku Klux Klan, generating a flurry of public protests that promptly nullified the deal.

In 1927, a Chicago attorney named Frank Hume aimed to acquire both the Sager and adjacent Martinal properties to develop the Sager Country Club, complete with a golf course and hotel.8 However, his grand vision crumbled when his assets were seized by the sheriff over a debt he was sued for, rendering his agreements void.9

By 1933, Chauncey and his brother Charles were the last surviving owners of the land that included Sager’s Lake, and they were both in their seventies and in retirement. The mill was no longer operating, and the brothers needed a buyer.

Chapter 2: Nudists from Chicago

A new group called "The Sunlight Club of Chicago" first made its debut in the club directory in the back of The Nudist magazine in August 1933, listed under a north Chicago address on North Damen Avenue. The Sunlight Club’s principal representatives were Chairman Clyde Terns, Director Rudolph Mischke, and Secretary Treasurer L. Bolling Weller, all from Chicago.10

That summer, the non-landed group of physical culturists was beginning to think of finding a permanent space within a reasonable driving distance from the city where they could gather nude, maybe even establish a community. Illinois’ law books specifically forbade mixed-sex nude gatherings, so Chicago area nudists belonging to non-landed clubs would travel to establishments in nearby Indiana, where the law was much more favorable to the practice—forbidding nudity only when it was explicit or sexual—or Michigan, where the laws were ambiguous.

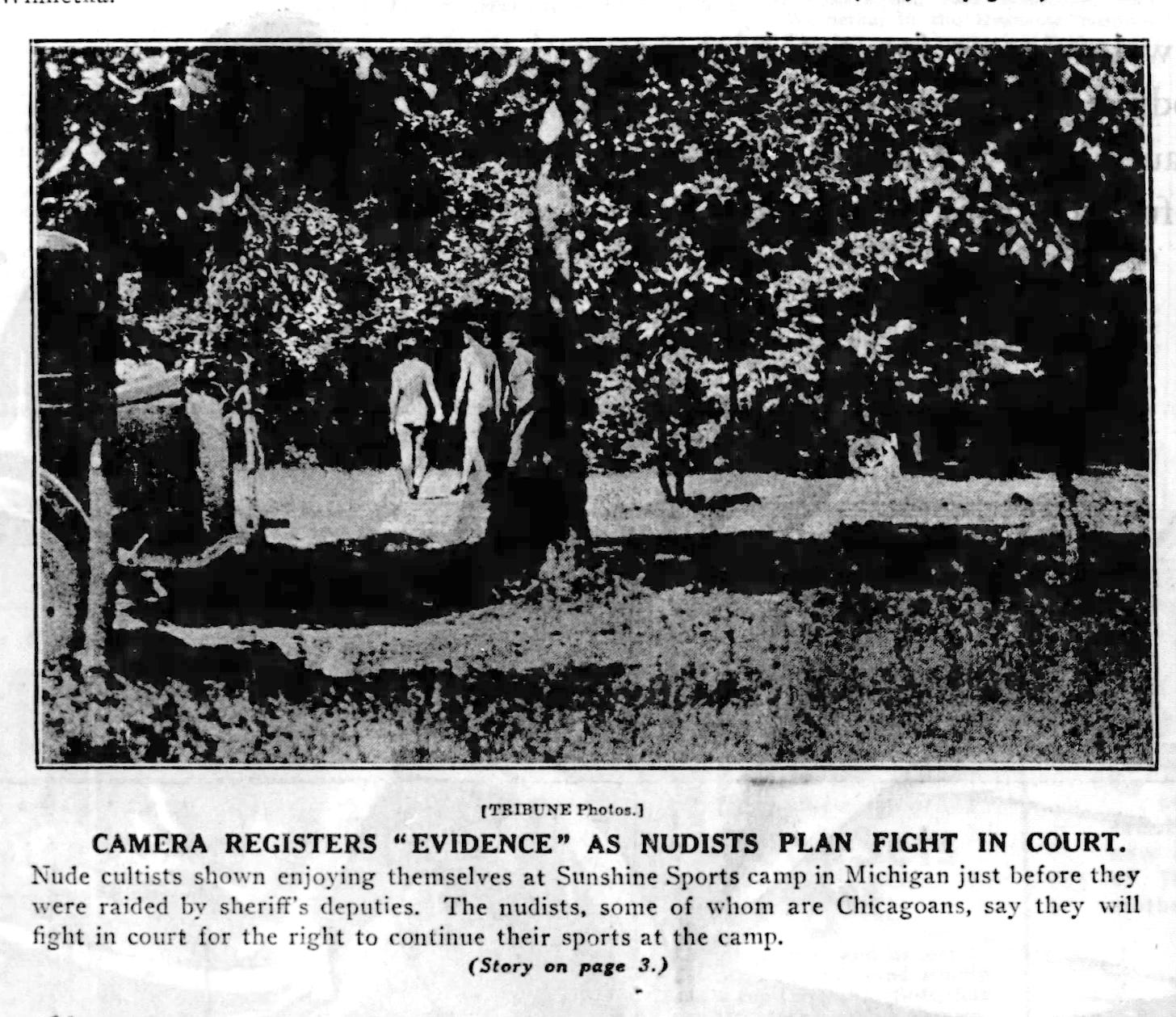

Up until that point, members of the Sunlight Club had been meeting infrequently at Sunshine Sports League near Kalamazoo, Michigan, owned by an ostentatious dance instructor named Fred C. Ring and his wife, Ophelia. Unfortunately, the Rings’ operation had been a little too ostentatious, and had allegedly been operating without the proper consent of local authorities.11 They soon caught the attention of the local Sheriff, Fred Miller.

Sunshine Sports League raid

On Labor Day, 1933, Fred Ring’s property was raided by sheriff’s deputies who had been spying from a nearby vantage point with a telephoto lens. Fred and Ophelia Ring were arrested, and seventeen others were served tickets for indecent exposure.

Among those seventeen named in the warrant were key members of The Sunlight Club of Chicago,12 including misters Terns, Mischke, and Weller, as well as their respective wives.13

Following the public release of the ticketed nudists’ names in the subsequent arraignment, the Wellers were accosted at their home by a Chicago Tribune reporter:

Mr. and Mrs. L. Bolling Weller were located yesterday at 7387 North Damen Avenue. Mrs. Weller, a woman who appeared to weigh about 160 pounds, was alone when a reporter first called. Asked concerning her alleged participation in the nudist colony, she said, "I'm not saying a thing. It's nobody's business. I don't see where you got the names, either."

Her husband, when reached, said he thought his wife was right and that he had nothing to say, either.14

The seventeen ticketed nudists ultimately had their charges dropped by a judge, but the Rings would be successfully prosecuted by a jury of elderly farmers and sentenced to sixty days in jail for indecent exposure, making them the first known martyrs of the American nudism movement.15

“Thus ended the first serious engagement between American nudism and the law,” the executive secretary of the International Nudist Conference, Rev. Ilsley Boone, wrote of the incident in The Nudist. “True, nudism in one way or another had previously faced the law in five other states, but in none of them had more than a nominal conviction been secured.”16

For the directors of the Sunlight Club of Chicago who had narrowly escaped the Rings’ fate, the shocking incident hastened their search for a secure property of their own, safe from prying eyes.

Within weeks, they found their spot; a scenic, private lake in Porter County, Indiana, in which Clyde Terns and his family had discretely skinny dipped during a recent visit. It was a spot that Terns’ daughter reportedly described as “a beautiful lake in the woods”, inspiring the club’s new name17—a spot which had just been listed for sale.

Rumors soon began circulating in Porter County about the prospective establishment of a nudist colony on Sager’s Lake.

On October 11th, 1933, Chicago Tribune announced:

Chicagoans Secure Indiana Site for Nudist Colony

Valparaiso, Ind. — A Chicago syndicate is reported to have secured an option on Sagers lake, southwest of this city, for a nudist colony. Plans are for fencing the property, consisting of 135 acres.18

By November of that year, Terns, Mischke, and Weller had signed a lease option on the Sager property, and the Chicago group, under the new name “Lake O' The Woods Club”, was first listed as an affiliate of the International Nudist Conference (INC).

A few months later, the club was officially incorporated by the trio as a not-for-profit entity in Indiana, listing as its objective, “to secure for members the beneficial results of out-of-door recreation and sports through physical culture.”19 By this time, the club already boasted over seventy members and growing.20

Lake O’ The Woods Club’s official establishment as a cooperative member-owned nudist club marked the beginning of a transformative journey which would continue at least ninety years into the present day. But as one might imagine, it would take the fledgling fraternity time to find its legs. In fact, the group was about to be faced with significant challenges.

Chapter 3: Yarrow’s crusade

In the Spring of 1934, with less than a dozen legitimate landed nudist clubs in the country, the media scandal over “nudist cults” setting up “colonies” in the United States was still novel, and the sensationalizing newspapers loved to frame their stories around this fear or distrust of unscrupulous cultists. Especially following the Fred Ring arrest, the media and law enforcement seemed to amplify the heat on nudists in the region.

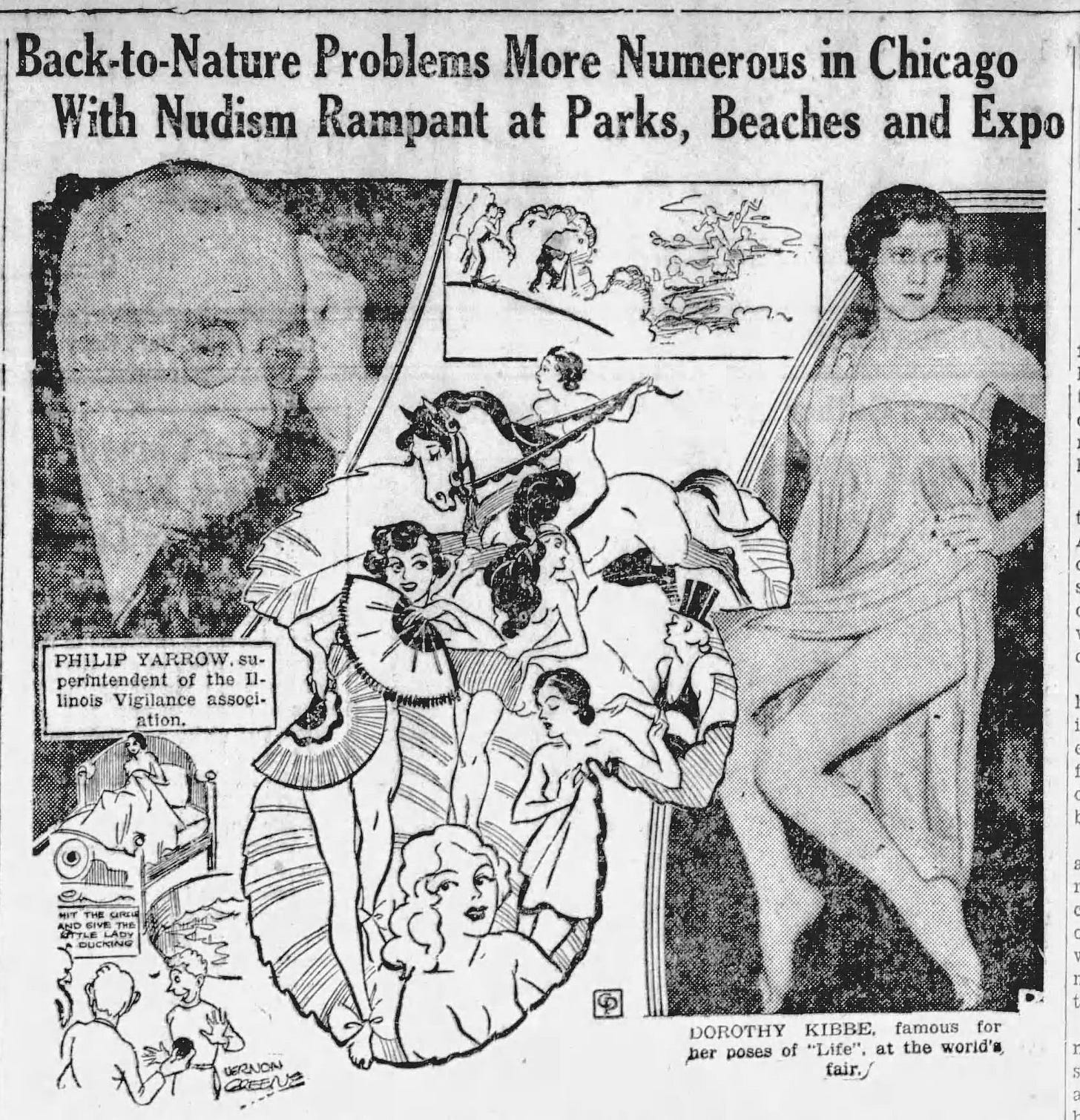

In Chicago, a notorious vice crusader named Reverend Philip Yarrow, the superintendent of a powerful anti-vice organization called the Illinois Vigilance Association, had begun raising alarms about nudism’s rampancy in the Chicago area.21

Yarrow had previously staged raids on brothels and speakeasies, battled with Al Capone and Chicago politicians he asserted were taking payola, and in 1933, as nudism’s popularity had begun to percolate around Chicago—with the city preparing to host the World’s Fair the following year—he’d determined it a threat worth campaigning on.

Under Yarrow’s direction, the Illinois Vigilance Association began scouting potential nudist activities “in various disguises.”22 His investigators also sought memberships in nudist groups to report on their activities.23 For months, the vice squad’s chief investigator Jack Brown kept tabs on a hotel where nude swimming had reportedly occurred in the pool.24

Three Links raid

On April 10th, Yarrow’s man Jack Brown and a gang of squad investigators and police raided the Three Links Hotel, just a few blocks from the North Damen Avenue home of L. B. Weller.

The news reports specifically named Lake O’ The Woods Club as the subjects of the raid, but revealed that the nudists—who rented the hotel’s swimming pool on a weekly basis for private use—were alerted of the police presence by the gym’s owner, William Feinberg, who was able to hold investigators off long enough for the swimmers to disperse from the pool and into the sex-segregated dressing rooms, saving them from indecent exposure charges.

When the officers charged into the dressing rooms and found roughly twenty nude men in one and a similar number of women in another, cops were reportedly left “blushing”25 and threatening to come back later and arrest Feinberg with a warrant.26

Just within the first year of their foundation as a membership group, the nudists behind Lake O’ The Woods Club had already been involved in two police raids, and had been written about in newspapers across the country.

It must have felt to members, on some level, like achieving some peace and privacy for their “back-to-nature” practices would never be possible.

Chapter 4: Fencing with the press

In an apparent attempt to shift the narrative and head-off any upset rumblings from their new Indiana community, Lake O’ The Woods issued a statement offering certain assurances; particularly that they would go about their nudism gradually, vowing to first don underwear until the nearby farmers could get used to the idea.

The story was picked up by Associated Press and reprinted in dozens of newspapers across the country.

It is unclear whether an attempt to adhere to this promise was actually performed, but the public announcement that they would hide that which they claimed they had no reason to hide effectively undermined the wholesomeness of the nudist idea that the group purported to represent.

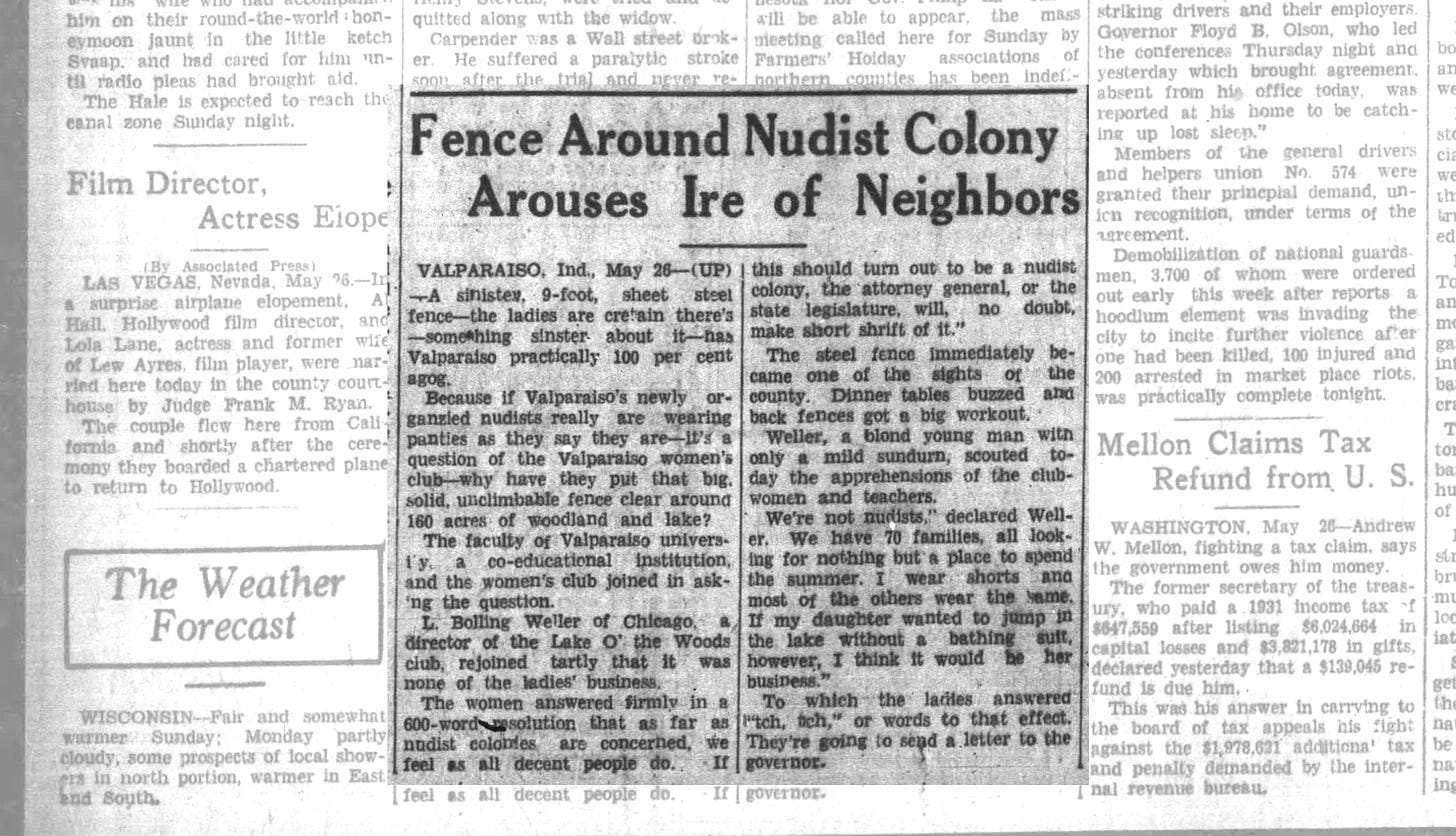

This, paired with the fact that the club had already begun the construction of a nine foot sheet steel fence to keep gawkers out, the announcement made the community more wary of the intentions of these Chicago outsiders, not less.

The steel fence, first installed the previous winter, began to cause considerable consternation from the surrounding community, representing the removal of this cherished natural space from the community’s use.

The nudists, meanwhile, ragged from their experiences with police raids and peeping vice investigators, relished in the lessons learned from prior club’s failures. One thing they’d learned from the Fred Ring raid was that a fence was key to protecting the views of their recreation from onlookers. In a winter issue of The Nudist in which the Lake O’ The Woods Club reported growth since their relocation to the Indiana land, excitement over the fence was expressed:

One of the directors of the club had an original idea for an all-steel solid fence, eight feet high, which it is believed will be cheaper and yet more durable and easier of erection than a wood fence. A section of this new fence thirty feet long is being installed for a test during the winter months.27

Still, neighbors gossip. According to an article published in May of 1934, “The steel fence immediately became one of the sights of the county. Dinner tables buzzed and back fences got a big workout.”28

Euphemizing nudism

When publicly questioned about the fence by the Valparaiso Women’s Club—who threatened to write a letter to the governor over the matter—Lake O’ The Woods Club secretary L. B. Weller responded publicly that it was “none of the ladies’ business,” and denied the charges of nudism. “We’re not nudists. We have 70 families, all looking for nothing but a place to spend the summer. I wear shorts and most of the others wear the same. If my daughter wanted to jump in the lake without a bathing suit, however, I think it would be her business.”29

Weller and company seemingly continued to rebuff the term “nudist” in their very first advertisement, which was printed in The Nudist magazine in May 1934, and referred to their group not as nudists, but as a "country club" for the practice of "free physical culture."30

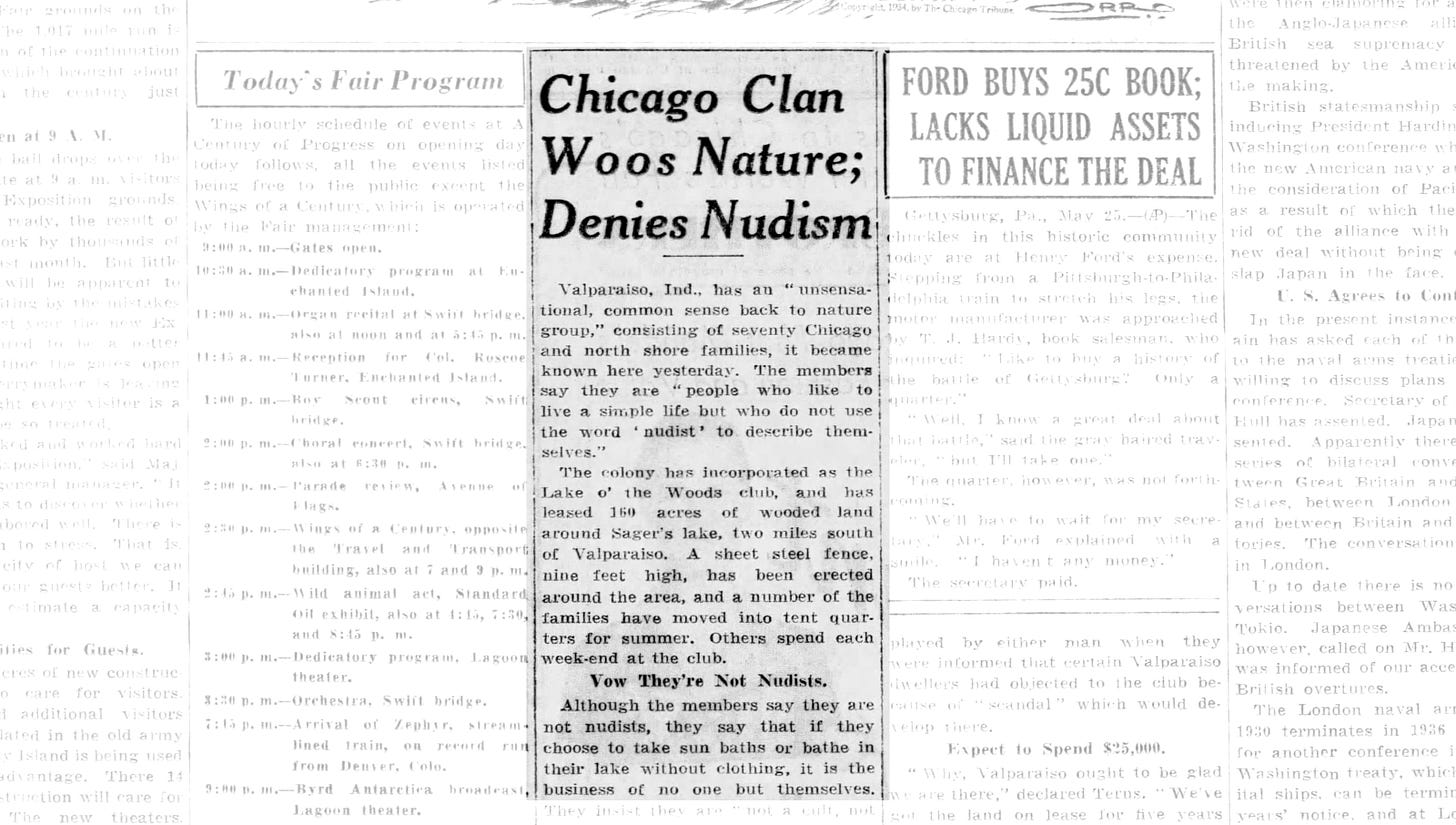

In a May 26th article in the Chicago Tribune titled “Chicago Clan Woos Nature; Denies Nudism” which named all three men—Terns, Mischke, and Weller—the group was said to “vow they’re not nudists”, and were quoted as saying they are “not a cult, not a sect, not vegetarians.”31

Clyde Terns was also quoted. "Why, Valparaiso ought to be glad we are there,” he said. “We've got the land on lease for five years but without question we are going to buy it. We expect to spend from $25,000 to $30,000 out there. We are a very select group. Every one of the members has to be married; it's all a family affair.”

Terns went on, "I don't think many people in Valparaiso object to us. We heard that most of the objection had been raised because the owner of the lake, which was used as if it was a public park for many years, had leased it to people who put up a fence and intended to make it private.”32

Sifting through the muck

With so much talk around the community about the Chicago nudists who had made Valparaiso their new home, it was only natural that the press wanted in. After all the negative coverage the group had received, they were naturally media-averse.

One reporter, after weeks of trying,33 finally made inroads with Clyde Terns, earning enough trust that he was granted an exclusive interview with the nudist camp founders.

That reporter was one A. J. Bowser, and his regular column in the Porter County Vidette-Messenger was called Siftings. In it, Terns and Weller invoked familiar religious imagery to appeal to the more prudent readers.

“Sacred history tells us that the first Nudist group was established in the Garden of Eden, and the first members were Adam and Eve.[…]

"Our goal is a healthy mind in a healthy body. This is not only a creed but a way of life. Light and air are vital conditions of human well-being. We believe these elements are insufficiently used in present day life, to the detriment of physical and moral health.”34

One week later, in a followup issue of Siftings, Mr. Bowser shared the full text of the Lake O’The Woods Club’s organizational bylaws, which had been furnished by Mr. Terns in good faith as evidence that there was nothing untoward with the business of their member club. At the end, the author concludes:

Siftings is neither pro nor anti on this subject. We have attempted to establish contact between the people of Porter county and the people who make up the Lake-O-The-Woods club. These people have come here to stay. They have obtained possession of the Sager property, and are developing it to accommodate their purposes.

Sager's Pond, once changed to Sager's Lake, now becomes the Lake-O-The-Woods. No longer will it be the mecca for the university students. No longer will they study “Sagerology” along its banks. No longer will the local people fish in the old pond. The old days are gone forever, and new days have come with their strange doings. In the old days when a horse saw an automobile the animal was frightened almost out of its wits. Who ever heard of a horse getting scared of an automobile these days. [sic] […]

Does nudism destroy shame? Clyde E. Terns says, “No. Instead, there is born in the mind of those and who practice nudism, an unconscious sense of innocence. Once the mind has been accustomed to seeing a naked person, the feeling of shock and surprise is gone, and there is no more of the unusual than there is when seeing a horse or any other animal.”35

Razing the past

The people of Valparaiso were apparently split over their new neighbors, with some supporting the operation, like A. J. Bowser tacitly did by giving the members a fair platform to make their argument.

Still, many more, including Bowser, mourned the loss of a cherished community resource that represented so much of the cultural history of their community. But, as the author expressed, the old days were gone forever. And shortly, when the Sager brothers—who still owned the land that the nudists leased—had their father’s old mill razed36 and (later) the iconic chimney stack leveled,37 altering the skyline so many in the community had known for generations, that sad truth was even more apparent.

Most associated nudism with new, progressive ideas, and its growth in popularity during this era was undeniable. It was during this time that nudism truly became an organized movement in America. On the other hand, its novelty and shock value made it an easy target for ambitious politicians seeking to build their reputation on a strong stance against the perceived menace of nudist cultists.

Chapter 5: Unexpected Terns

When the McCall-Dooling Bill was introduced in 1935 by New York State Senator John T. McCall, it seemed very likely to “die in committee.” In fact, during the bill’s first hearing, even the senators who introduced the measure opted not to argue for it.

Among those reported present to speak in opposition to the proposal to prohibit “meetings of three or more unclothed members of both sexes” included a leader from a humanist church, a representative of artists, anti-censorship advocates, and the executive secretary of the International Nudist Conference, Rev. Ilsley Boone.38

Boone and bust

Despite predictions, the McCall anti-nudist bill survived, due largely to its endorsement by former New York Governor Alfred E. Smith.39 Smith was on the back side of his political career in 1935,40 but as the head of the New York Decency League which had succeeded in getting the anti-nudist measure introduced, he was still a powerful player in New York politics, and had championed the bill as his pet project.

Large protests from nudists and other civil liberties advocates did not stop the New York state legislature from passing the McCall bill with an overwhelming majority in April, expressly banning nudism in the state of New York for good.41

Nudist leaders were outraged. Ilsley Boone, claiming a coalition of 2,000-3,000 nudists, told press, "So far as I know these camps will continue to operate and will test the legality of this law in the courts, if necessary. […] Reports that some of the leaders were looking for camp sites in New Jersey because of the New York restrictions you can classify as absolutely false. None has looked because he feared the anti-nudist law."42

Despite his statement, within just a few months, Ilsley Boone bought and eighty-acre plot of land in New Jersey and established Sunshine Park to become the headquarters of American nudism.43 A minor exodus followed, with multiple groups moving over state lines to continue their operations. But the threats that New York state saw were not isolated to the borders of that state.

Michigan follows

In 1935, the Michigan legislature took up consideration of an anti-nudist measure which had been introduced by Representative Chester Fitzgerald, and by all accounts had copied the pending McCall bill’s text word for word. Ilsley Boone later commented, “not a phrase nor a comma was changed.”44

A more profit-oriented Clyde Terns might have looked at the potential legislation in his neighboring state as an economic opportunity. After all, Lake O’ The Woods club was just over the border from lower Michigan. Instead, he rightly saw the bill as a threat to his group and their way of life.

When the Michigan’s fourteen-member judiciary committee held a hearing on the bill in March, four nudist leaders from the region appeared to speak against the bill.45

One of the men was an author and lecturer by the name of Elton R. Shaw, who owned a publishing company, and would later write a book covering the legislative events in New York and Michigan called The Body Taboo.46 Shaw first became interested in the nudism movement after learning of the prosecution of Fred Ring, whom he believed had been “railroaded” and got a “raw deal.”47

Another one of the speakers was Clyde Terns.48

Following their comments, when Committee Chairman George Watson asked any defenders to stand up in support of the bill, no one spoke. Reportedly, several ministers who had been planning to speak backed out, believing the bill was defeated by the eloquence of the four speakers.49

They were right. The bill never made it past the committee. It was defeated unanimously.

A threat neutralized

Early nudists faced adversity from legislators, authorities, moralists, and the media forcing them to be organized and activated.

As nudism became more accepted, many of these challenges subsided over time. However, out of the various legal and existential threats faced by the nudists of Lake O' The Woods Club in their 90 year history, one of their most formidable and longstanding foes was no more than a simple potato farmer.

Chapter 6: Shameless Amos

With word spreading around Porter County and beyond about the nudists at Sager’s Lake, spectators were naturally drawn to the site. Moreover, some in the region were not ready to let go of what had previously been an accessible public resource.

Before long, strangers began appearing on the lake, some merely fishing, but others evidently leering at the nude recreationists.

With most of the access points to the lake either fenced off or inaccessible due to the natural geography, it wasn’t hard for the nudists to deduce that the lecherous looky-loos were coming from Martinal’s farm.

Amos Martinal was the nudists’ east side neighbor, an enterprising farmer from Switzerland who had resided on adjacent land since 1917 raising chickens and growing a variety of vegetables. Seeing an opportunity, Martinal began selling access to the lake through his own property, which had a small beach and a pier from which canoes could be launched.

In April of 1935, the Sager brothers, who still owned the land being leased to the Lake O’ The Woods Club, soon filed an injunction against Amos Martinal in an Indiana court, charging the farmer with “permitting promiscuous boating.”50

The action kicked off a legal war which would persist over multiple courtroom battlefronts for 40 years.51

The first twenty years

It was almost two years before the first major judgment was made in the conflict, by Porter County Superior Court judge Mark Rockwell,52 ruling that the Sagers had ownership of the land under Sager’s Lake, giving the nudists exclusivity. The court established the lake's private nature and affirmed that whoever owned the land also owned the water, and determined that Martinal’s property ended at the shoreline.53

Eventually it was resolved that the nudists would pay Martinal annual rent of $175 to effectively lease his beach frontage for their private use,54 and the farmer would no longer allow paying visitors on his property.

In February of 1941, Chauncey Sager died of a stroke.55 The nudists, who had been leasing the lake property with the option to buy, officially purchased the title from the Sagers, and continued paying Martinal the annual fee. In 1945, Charles Sager died.56

There were occasional dust ups between the nudists and their neighbor, but their arrangement held firm for eighteen years.

Then, in 1953, the nudists stopped paying.

Comebacks for bygones

Quick to notice the sudden hit to his income, Amos Martinal “got into the parking lot business”57 and again began opening his lakefront to visitors, charging one dollar per head to picnickers.

"I got a right to do it." Martinal told reporters. "About five to 10" people would visit most days to picnic, fish, or "spend an afternoon in the shade by the water."58

But as one report put it, “before they leave they usually drink in a lot of scenery as nudists romp about in the raw at the adjoining 270-member [Lake O’ The Woods Club].”59

In July, Lake O’ The Woods Club filed a new injunction suit against Martinal for infringing their privacy. Two months later, Starke Circuit Court Judge Robert Lundin ruled “that Martinal's parking lot was a legitimate private enterprise, and that the 75-year-old farmer was merely exercising his ‘valuable riparian’ rights.”

Suddenly, Lake O’ The Woods had a privacy problem.

Two more decades of hurdles and squabbles

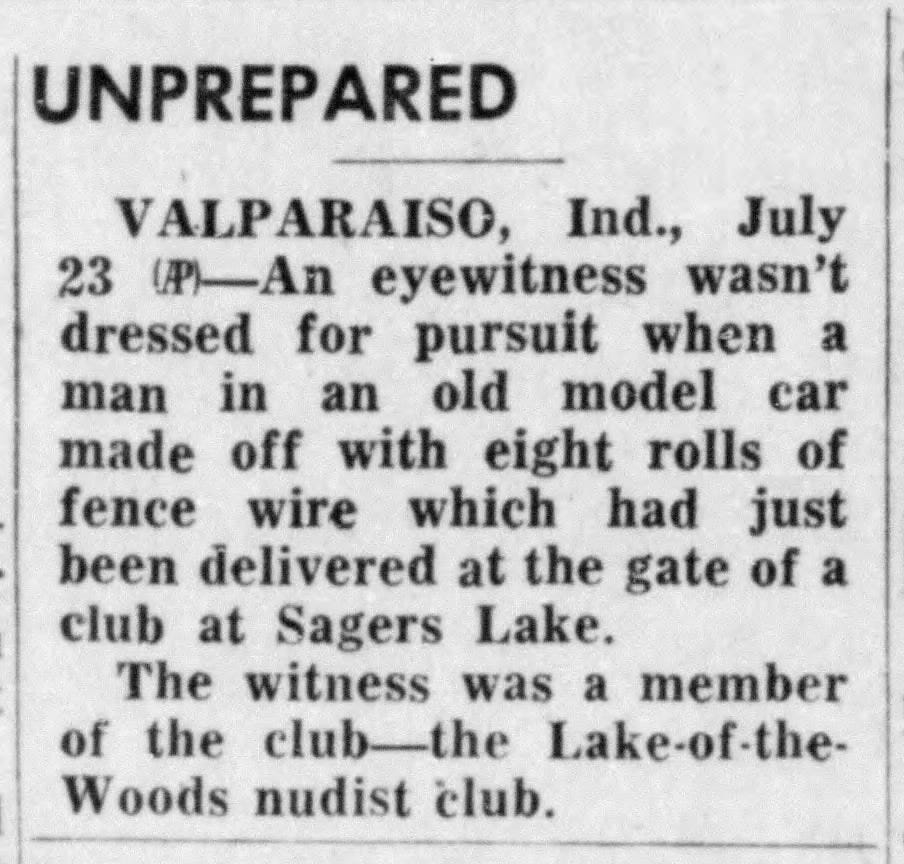

For the next ten years, the nudists faced multiple squabbles, thefts, and other issues from lake invaders. These battles intermittently cropped up in the press.

In 1956 they landed in papers after Erwin Meuller, a 20+ year member and director of the club, got into an altercation on the lake with a fisherman named Otto Ward, who stepped onto Meuller’s boat and a scuff ensued. Civil and criminal charges were filed against Ward,60 later dismissed.61

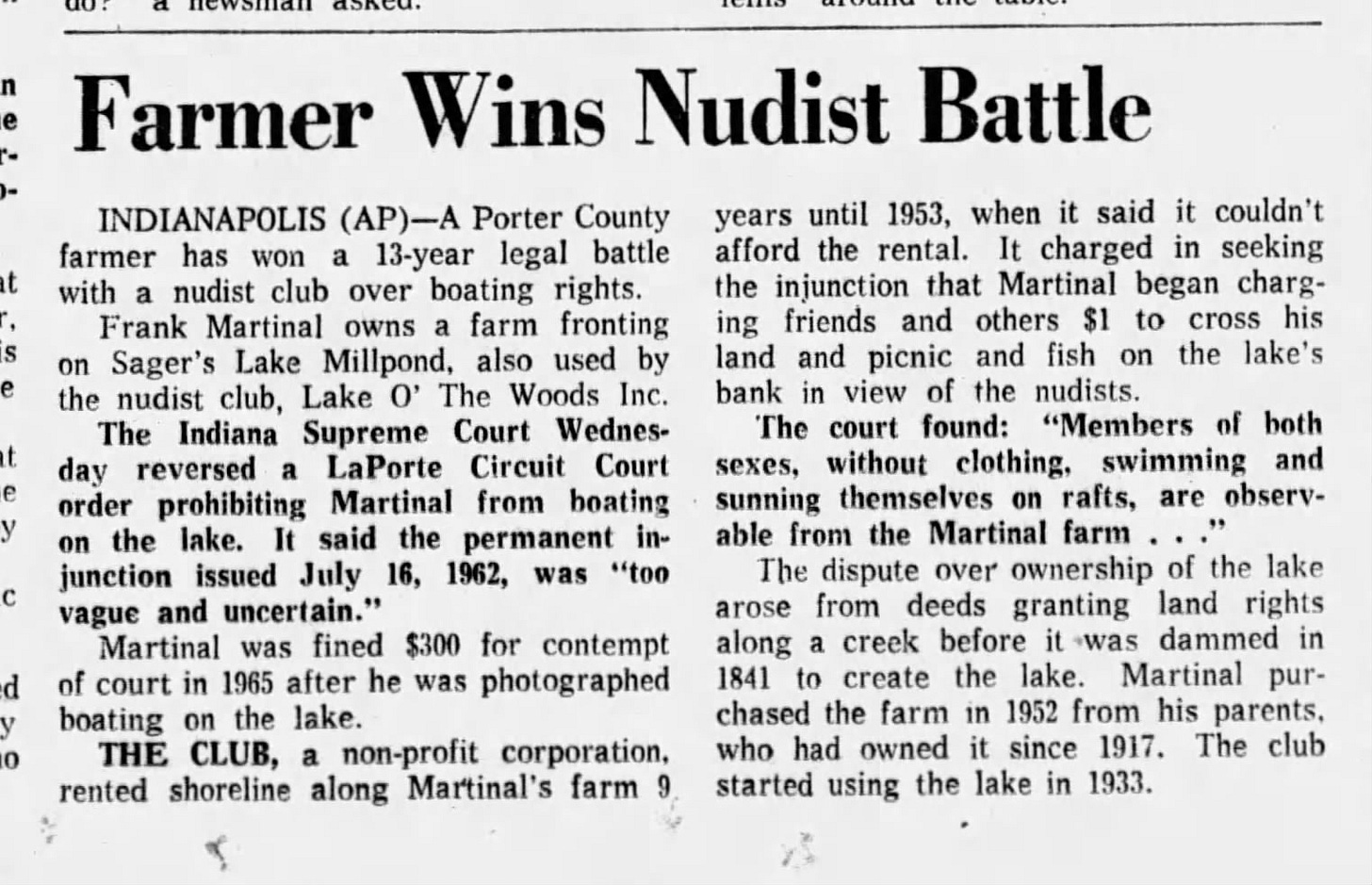

The club attempted other legal avenues of stemming the problem, such as filing a Quiet Title lawsuit against Amos and his son Frank martinal in 1956;62 petitioning a judge to prevent public boating on Sager’s lake in 1957;63 and appealing to the Indiana Supreme Court to overturn the standing ruling in 1958.64

In 1962 the nudists won an injunction against Martinal, prohibiting him from boating on the lake.65 But it was clear that Martinal wasn’t the only problem. Less than two weeks later, the club installed a new length of fence across their portion of the lake, blocking view and access to boats launched from Martinal’s beach. Within days, three men were arrested for stealing portions of the fence.66

More lawsuits and appeals were filed between the parties, and the conflict continued back and forth for another decade, with both sides experiencing wins and losses.67

The fight outlived Amos Martinal, who died in 1965 at age 86.68

His son, Frank, had a win in 1967 when the Indiana Supreme Court reversed the injunction issued against Martinal five years earlier, in 1962. Of course, the battle would wage on.

Clyde Terns died with his wife the next year, in 1968, in a house fire. The couple was in their seventies, and had recently relocated full time to Valparaiso from Chicago.69

An unexpected conclusion

The battle between the Lake O’ The Woods Club and the Martinals finally came to an end in 1971, when Frank Martinal, age 52, and his wife, 45, died tragically in a car accident.70 Valparaiso mourned the loss of a well known figure in the community.

Martinal’s untimely death may have marked the end of a long legal conflict between the two parties. However, for the nudists who continued to reside on Sager’s Lake, it would not be the final fight they would encounter in the name of protecting the sanctity and seclusion of their beautiful lake in the woods.

As the history of Lake O’ The Woods Club shows, in this society the threats posed against nudists and nudism are ever present.

Chapter 7: Nudists convene

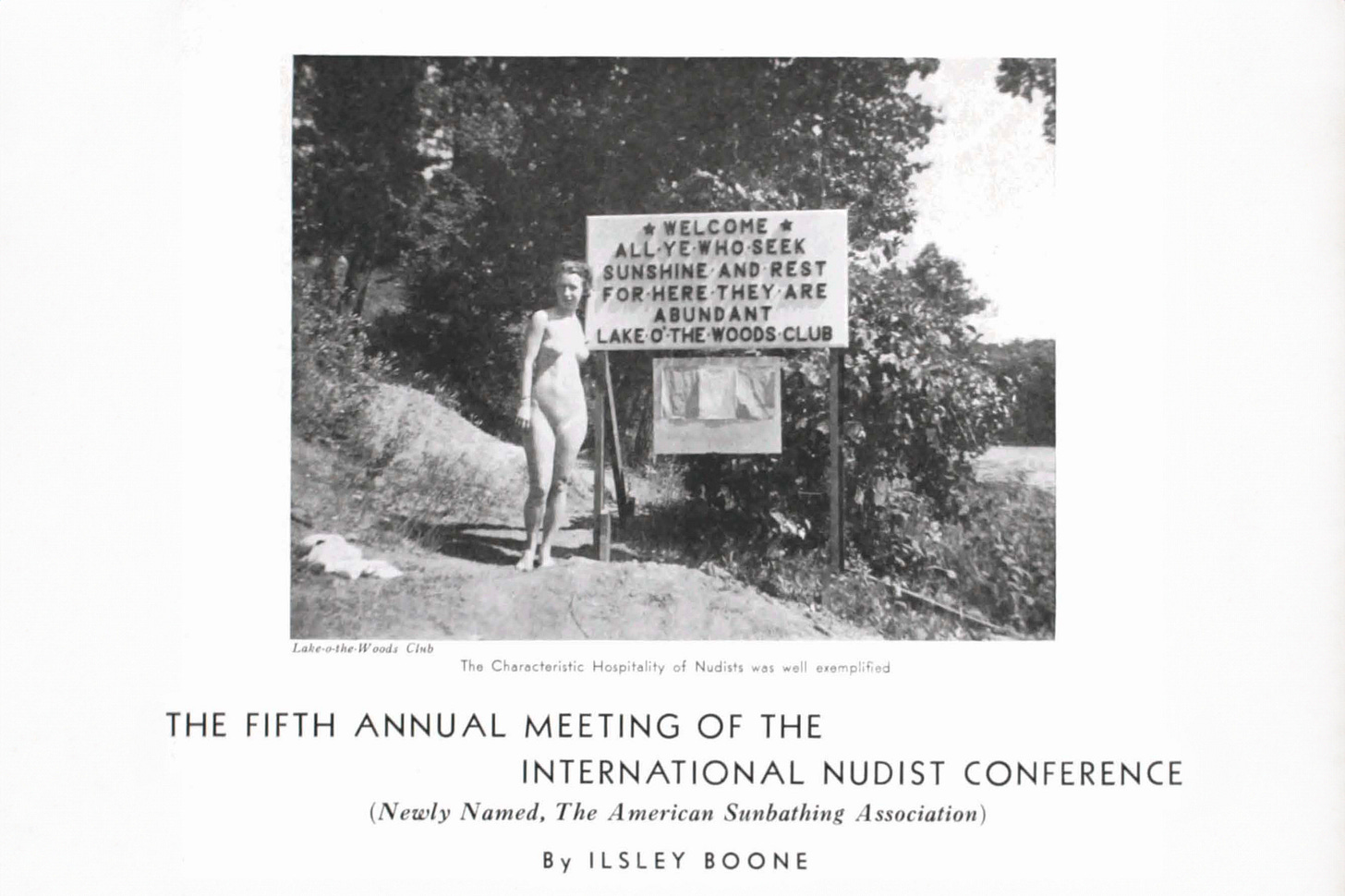

After more than five years of organizing against a variety of existential threats—including police raids, sensationalist media, and legislative prohibition—nudist leaders and delegates from more than forty affiliated groups convened on August 22, 1936, in Valparaiso, for the fifth annual International Nudist Conference, hosted for the first time by Lake O’ The Woods Club. The weather was warm and mild, providing ideal conditions for a busy weekend of event-filled days, bookended by morning swims and evening campfires on Sager's Lake. Over 200 individuals attended.71

“It really is a park of rare charm and attraction, with cleared woods, rolling hills and dales, and a matchless lake.” Ilsley Boone wrote in his convention report for The Nudist. “It is doubtful if any other local group possesses a property so pre-eminently suited to the needs and the purposes of sunshine living as are found in this delightful spot.”

Groups from far and wide were represented, including new clubs in California, Colorado, Florida, even one attendee from England. “New York was well represented and it became evident that nudism is still growing in the Empire State notwithstanding Al Smith's damn fool piece of anti-nudist legislation,” Boone wrote. “It will not be long before Al will want to get rid of that stigma more than any dog ever wanted to get rid of the tin can tied to its tail.”

Looking forward

The convention program and the planned speeches for this particular annual meeting focused on four main themes: “The connection between nudism and education, the role of publicity in the nudist movement, the growth of the national nudist community, and nudism's position in a shifting social landscape."72 These themes reflected a progressive vision that nudists leaders had developed from lessons learned over the previous half decade.

The convention saw the nomination and election of INC’s third president, Elton R. Shaw, the eloquent author from Michigan who had defended nudism to his state’s congressional committee one year prior. Shaw’s forward-looking rhetoric was well suited for this ambitious moment.

“Within [ten] years I sincerely believe that on every American bathing beach there will be a separate, fenced-in portion for those who have no superstitions about so-called indecency of the naked body,” Shaw told the press. “Of course they will not be permitted to mingle with those who still cling to the old beliefs.”73

Hindsight makes this particular statement seem silly from 2023, but in 1936, it reflected the trajectory of growth that American nudism had seen to that point. The movement had gone from a quaint foreign niche nearly nobody ever spoke of, to a significant organization of groups that were discussed in the newspapers with some regularity, in a matter of less than a decade.

Starting anew

On a recommendation from the INC’s Findings Committee, the conventioneers at Lake O’ The Woods also voted for a rebrand for their movement. Effective immediately, International Nudist Conference would officially be changed to the American Sunbathing Association. Their magazine, The Nudist, which had already been beset by censorship and legal challenges from the United States Postal Service,74 was to make a phased change to the more discreet title Sunshine & Health over the next two years.

“The reason given for these changes,” Boone wrote, “was that no sooner had the nudist movement in this country succeeded in fixing the connotation of the words "nudist" and "nudism" than these terms were seized upon by burlesque theater managers, night club troupes, disorderly road houses, and exposition side shows to further their own business enterprise in the field of commercialized pornography. Even the national press services have referred to psychopathic nakedness as ‘nudism.’ So lamentable has been this abuse of two perfectly good words that in the interest of dissociation of the nudist movement from the morbid and burlesque types of nakedness, these terms shall hereafter be left almost exclusively to the theatrical, the night club and the pornographic fields.”

As a group, they had been beleaguered by attacks from the press and authorities, but with a sense of starting fresh and looking forward to more growth and acceptance, optimism permeated the air. Together at Lake O’ The Woods, before the serene backdrop of Sager’s Lake, the nudists drew plans for a future that transcended the legal and societal confines they had encountered. Those challenges of the past were no longer the defining story. The defining story was one of resilience, growth, and a collective vision for a better society.

Epilogue: 90 years later

It's evident that the progressive ideas and practice of nudism by the early leaders of Lake O' The Woods Club generated some opposition in the surrounding community. This friction wasn't solely due to their nudist lifestyle; it also stemmed from their exclusive use of Sager's Lake, a resource that the local community had relied on for recreation, farming, and industry for generations. When you begin to think of what that loss might have felt like to a fisherman in 1933, it’s almost hard not to side with the clothed community over the nudists.

But after a generation or two passed, the collective memory of Sager’s Lake faded. The problems faced by the club did not go away, but they quieted.

To the vast majority of the nudists who enjoyed the beauty that Sager’s lake offered, through memberships and day trips, summer visits and activities on the lake, many of those early battles were in the peripheral to begin with.

For most, the legacy of Lake O’ The Woods Club is one of joy and celebration, but still with a sense of triumph over adversity.

One longtime member, Dr. J. Carey Davis, who had been with the club since their early days as a non-landed group and brought his family to the club for summers throughout the 1930s and 40s, later compiled a collection of verses and limericks he and his son, D. E. Davis, had written about Lake O’ The Woods club between 2002-2006. One lyrical entry went:75

Dad's #7774: The founders of Lake-O-The-Woods. Were men and women of courage and vision. They guided the club through parilous times, With wisdom and many a great decision. This place, for us, for more than fifty years, Was a bit of Paradise, seemingly without end. The memories of happy days spent there, Will last as long as we live, my friend. [Dr. J. Carey Davis]

Sunshine and rest

Now, recognizing the lake's rarity, its well-preserved natural beauty, and the club's century-long commitment to the lake’s protection, it stands as a rare, untarnished space that can only be enjoyed in one's most natural state—a true jewel to behold.

As I learned during my visit, to enjoy Sager’s Lake today feels a little bit like stepping back into 1935, when the nudists gathered there from nearby Chicago, Gary, or Kalamazoo as an escape from the stresses of the real world. The welcoming mantra from that era still resonates:

“Welcome all ye who seek sunshine and rest for here they are abundant”

Despite its rustic nature, the club is not behind the times. They’ve adapted a model that has evolved with the world. Their lodging, uniquely, is booked entirely through AirBnB, an adaptation that has opened their club up to a whole new crop of first-time naturists and people under 40. Built on the co-op model established by its founders ninety years ago, the club has successfully staved off commercial exploitation, a challenge many other organizations fail to overcome.

Over the course of its 90-year legacy, Lake O’ The Woods Club has not avoided those challenges; it has met them. Surely, new threats will crop up.

Yet, the spirit of that small group from Chicago in 1933 clearly lives on, and Lake O’ The Woods endures as a beacon for the nude-inclined, a testament to the allure of a life lived freely and in harmony with nature. 🪐

Get a t-shirt, support Lake O’ The Woods Club

This is an unpaid endorsement. I just genuinely love my Sager’s Lake / Lake O’ The Woods Club 90th anniversary t-shirt. Not only is the art awesome and it’s a great fit, but it’s just $20 and the purchase supports the club. It’s an easy way to do that without paying a visit in person. But still, plan one of those as soon as possible too.

“City’s First Horse Show to be Held May 27” May 16th, 1933. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 2.

Collier, Azure. “Students working to bring landmark back to VU campus: Building a bridge to past” August 9th, 2004. The Times (Munster, Indiana), 68.

Shook, Steve. “Ice Industry of Porter County” August 31, 2017. PorterHistory.Org http://www.porterhistory.org/2017/08/ice-industry-of-porter-county.html

“Court Rules Sagers Have Title to Land” May 1st, 1937. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 1.

Shook.

“Fifteen years ago; July 25, 1918”. July 25th, 1933. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 4.

“Sager’s Lake Region to be Fine Resort?” August 26th, 1927. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 1.

“Attach Sager Lake Ground” February 10th, 1930. The Times (Munster, Indiana), 3.

“Incorporations”. February 7th, 1934. The Indianapolis Star, 15.

Cinder, Cec. (1998). The Nudist Idea, p. 533. UltraViolet Press.

Wallace, Howard. “Lake O’ The Woods Club Turns Eighty; Some Insights To Its Early Days”. July, 2013. The Bulletin, 12-13.

McLaughlin, Kathleen. “2 Nudist Camp Leaders Move to Fight Case”. September 10, 1933. Chicago Tribute, 3.

Ibid.

Cinder.

Boone, Ilsley. “Nudism on Trial in Allegan” December 1933. The Nudist.

Wallace.

“Chicagoans Secure Indiana Site for Nudist Colony”. October 11, 1933. Chicago Tribune, 22.

“‘Back to Nature’ Club is Active at Sager’s Lake”. April 23, 1934. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 2.

“Nudism: We Grow in Chicago”. December, 1933. The Nudist, 24.

“Nudists Plan Indoor Colony In Hotel Here”. December 1st, 1933. Chicago Tribune, 2.

Grant, Bruce. “Back to Nature Problems More Numerous in Chicago With Nudism Rampant at Parks, Beaches and Expo”. August 8th, 1933. Morning Free Press, 2.

“Three Memberships in Nude Cult Proves It's No Skin Game”. April 26th, 1934. The Paxton Record (Paxton, Illinois), 6.

Chicago Tribune (n. 21)

“Blushing Cops Raid Nudist Swim Pool And Receive Jeers”. April 15th, 1934. The Springfield News-Leader (Springfield, Missouri), 1.

“Ahem! They Were Nudists Boys and Girls”. Apriul 16th, 1933. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 1.

The Nudist, (n. 20).

“Fence Around Nudist Colony Arouses Ire of Neighbors”. May 27th, 1934. Leader-Telegram (Eau Claire, Wisconsin), 1.

Ibid.

Wallace.

“Chicago Clan Woos Nature; Denies Nudism”. May 26th, 1934. Chicago Tribune (Chicago, Illinois), 1.

Ibid.

Bowser, A. J. “‘Siftings’ Gains Interview with Nudist Club”. September 14th, 1934. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 4.

Bowser, A. J. “Siftings”. September 18th, 1934. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 1, 8.

Bowser, A. J. “Siftings”. September 25th, 1934.Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 1, 8.

“Historic Sawmill Being Razed” July 21st, 1934. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County (Valparaiso, Indiana), 7.

“Old Chimney is Razed at Sager Mill” Jun 26, 1937. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 1.

“Anti-Nudist Drive a Flop at Hearing” February 6th, 1935. Daily News (New York, New York), 388.

“Adam and Eve Wore Leaves, Says Anti-Nudist Bill Debater” April 16th, 1935. The Herald Statesman (Yonkers, New York), 3.

Al Smith. (2023, August 28). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Al_Smith

“Smith Anti-Nudist Bill Passed As Play Without Clothes” April 16th, 1935. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, New York), 1.

“Nudists to Defy Ban of Governor” May 13th, 1935. TheStandard-Star (NewRochelle, NewYork), 3.

Cinder, 556-557.

Boone, Ilsley. “Three Glorious Days”. November, 1935. The Nudist, 33.

“Nudists Defend Right to Discard Clothing” March 15th, 1935. The Herald-Palladium (Benton Harbor, Michigan), 10.

Shaw, Elton R. “Fair Trial or Persecution?” October, 1934. The Nudist, 8.

Saw, Elton R. (1937). The Body Taboo, 227. Shaw Publishing Company.

“Nudists Choose Local Man Head” August 24th, 1936. Lansing State Journal (Lansing, Michigan), 2.

The Herald-Palladium. (n. 45).

“Flashback: 54 Years Ago”. June, 1990. Bare In Mind, 15.

“Delay Valpo Nudist Colony Peek-a-boo Suit”. Jun 21, 1956. The Times (Munster, Indiana), 13.

“Meanest Men”. April 29th, 1935. The Republic (Columbus, Indiana). 7.

“Lake is Issue”. February 5, 1937. The Richmond Item (Richmond, Indiana), 2.

“Court Rules Sagers Have Title to Land”. May 1st, 1937. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 1.

“Nudists Feud in Circuit Court with Farmer”. July 16th, 1954. The Commercial-Mail (Columbia City, Indiana), 8.

“Stroke Fatal to C. A. Sager at Age of 80”. February 10th, 1941. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 1.

“Chas Sager Dies Sunday”. November 26th, 1945. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 1.

“Farmer Owning Lot Next to Nudist Colony Sees Profit”. August 10th, 1954. The Commercial-Mail (Columbia City, Indiana), 5.

The Commercial-Mail (n. 54).

“Farmer Cashes In Renting Space Near Nudist Colony”. July 16, 1954. The Indianapolis Star, 1.

“Civil Suit Filed as Aftermath of Sagers Lake Tiff”. June 27, 1956. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 10.

“Criminal Hearing is Transferred to Circuit Court”. June 29, 1956. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 3.

“Court Notes”. May 27th, 1958. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 6.

“Court Notes”. November 6th, 1956. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 6.

“Halt Asked To Boating on Sager's”. September 9th, 1957. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 3.

“Court Notes”. October 28th, 1958. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 6.

“Lake of Woods Dispute May Be Reopened”. December 12th, 1958. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 1.

“Sight-Seeing Anglers Ruled Off Nudist Lake”. July 19th, 1962. Evansville Courier and Press (Evansville, Indiana), 29.

“Second Man Faces Charges in Fence Stealing Episode”. July 23, 1962. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 6.

“Seek New Trial in 9-Year Old Issue Over Lake”. May 18th, 1963. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 3.

“Nudist Club Goes to Circuit Court”. July 5th, 1963. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 6.

“Neighbor of Nudists Appeals Court Ruling”. November 28th, 1963. The Star Press (Muncie, Indiana), 18.

“Appellate Court Rules in Favor of Lake O' The Woods”. July 20th, 1965. The Star Press (Muncie, Indiana), 1.

“Court Upholds Nudist Club in Fight over Lake Rights”. July 13th, 1965. The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana), 11.

“Farmer wins Nudist Battle”. April 20th, 1967. The Star Press (Muncie, Indiana), 1.

“Ruling Won by Nudists is Reversed”. April 20th, 1967. The South Bend Tribune (South Bend, Indiana), 43.

“Judge Halts Ogling of Nudist Camp”. May 4th, 1967. The South Bend Tribune (South Bend, Indiana), 4.

“Hearing on Restraining Order Opens”. May 15th, 1967. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 6.

“Anglers 'Spare Rod' at Sager Lake”. May 7th, 1967. The South Bend Tribune (South Bend, Indiana), 2.

“Hearing on Plea Slated”. November 30, 1967. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 19.

“New Sagers Lake Action”. July 22nd, 1968. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 6.

“Amos C. Martinal; Obituary”. May 17th, 1965. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 6.

“Fires Take Three Lives”. February 10, 1968. The South Bend Tribune (South Bend, Indiana), 14.

“Frank Martinal, Wife Car Victims”. March 1st, 1971. Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, 1.

Boone, Ilsley. “The Fifth Annual Meeting of The International Nudist Conference (Newly Named, The American Sunbathing Association)” November 1936. The Nudist, 7-9.

Ibid.

“Nudists Choose Local Man Head” Lansing State Journal (Lansing, Michigan) · 24 Aug 1936, Mon · Page 2

Ibid.

Davis, John Carey & Davis, Don Edward. “Lyrics from the Lake: Poems and Limericks about LOWC”. Unpublished. Courtesy of Lake O’ The Woods Club.

I spent a lovely day at Lake of the Woods on a business trip to Chicago about 20 years ago. That tranquil day stands out vividly in my mind still. Truly one of the most unique, beautiful and idyllic locations of any club I’ve had the joy to visit or belong.

WOW, that was a long and well researched email. Not a place I could ever visit, but I am certainly in favor of more nudism, whether it be at a private resort or in general public.